Anatomy of Moncrieff's Anti-Medication Playbook

A 3-step strategy of attacking medical psychiatry

This is a follow-up to:

Dummies Guide to “The British Professor Leading the Controversial Backlash Against Antidepressants”

Over the years, it has become clear to me that the British critical psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff, described by the Times as “the British professor leading the controversial backlash against antidepressants,” has a carefully honed 3-step strategy of attacking psychiatry, which she has used with remarkable power against the medical establishment.

Step 1: Identify a narrow, technical assertion pertaining to the neurobiology or medical treatment of mental health problems, and show that the evidence supporting that assertion is not as strong or high quality as commonly believed.

Step 2: Use the uncertainty of evidence to make the claim, or imply, or pretend that the assertion has been shown to be false. [This step is a logically invalid inference since weak evidence in favor of thesis A does not equal strong evidence in favor of inverse A.]

Step 3: Use the claim as a stepping stone to bash medical psychiatry by making claims that extend far beyond the scope of the narrow, technical assertion in step 1. Rely on rhetoric, ignorance of the audience, and prevalent prejudices to pull this off, and make strategic motte-and-bailey retreats when needed.

This 3-step attack is bolstered by 2 ancillary moves:

Make isolated demands for rigor, and set the required bar of evidence to a level that favors one’s own position, while simultaneously lowering the bar or shifting the burden of proof when it suits your favored positions.

Pretend your personal opinion carries the same epistemic weight as the clinical consensus of the medical community.

In a previous post, Reflections on the Recent Controversy Around Lithium and Suicide Risk, I have described in detail how Moncrieff used this strategy against lithium.

Step 1: Moncrieff and colleagues argued in a meta-analysis that the evidence from randomized clinical trials is inconclusive regarding whether lithium reduces the risk of suicide or suicidal behavior, and more data are needed to estimate the effect of lithium with more precision.

Step 2: Moncrieff used this to publicly proclaim that she had demonstrated that lithium has no effect on suicidality and that this is simply a myth. She also completely ignored other sources of evidence, such as large nationwide observational cohort studies.

Step 3: Moncrieff used this as an opportunity to bash lithium as a psychiatric treatment, denied that it is an effective treatment for bipolar disorder, said that it is “just a toxic sedative,” and said that psychiatrists prescribe the drug because it makes them “feel that they are proper doctors.”

This is also the exact strategy Moncrieff has used with depression and antidepressants.

Step 1: Moncrieff and colleagues conducted an umbrella review showing that evidence in favor of depression being caused by a serotonergic dysfunction is weak and inconsistent.

Step 2a: Moncrieff acted as if she had demonstrated that an absence of serotonin dysfunction in depression has been demonstrated.

Step 2b: She repeatedly implied that this challenges the idea that antidepressants are effective treatments for depression, since there is no serotonin dysfunction to fix.

Step 3: She used this as a basis for a full-scale public attack on antidepressants, denying that depression even requires medical treatment, that antidepressants have no appropriate clinical use, and any perceived benefit is small and due to nonspecific blunting effects.

The success of Moncrieff’s campaign against antidepressants relies on the popular misconception that antidepressants work by reversing a serotonin deficiency. The “chemical imbalance” narrative is scientifically unsupported, but its antithesis has the additional feature of being logically invalid. Reversing a serotonin deficiency is indeed a possible way for a drug to be effective, but saying that a drug does not reverse a serotonin deficiency does not demonstrate that the drug is ineffective.

Any honest physician would have admitted so publicly instead of repeatedly implying otherwise.

I have devoted considerable attention to discussing Moncrieff’s work in the past, and perhaps devoting further attention is unwise, but Moncrieff’s response on her personal blog to my earlier Substack post and the subsequent Twitter discussion give me the opportunity to say things that I believe will be useful for readers of Psychiatry at the Margins.

In discussions around the neurobiology of depression, Moncrieff wants to have her cake and eat it too. She wants to acknowledge in some unspecified way that “something is going on in the brain when people are depressed,” but she also wants to maintain that nothing specific can be said about what is going on in the brain of a depressed person, and furthermore, she seems to want to deny that what is going on in the brain of a depressed person can be intervened on medically to improve the depression. In addition, Moncrieff does not want to acknowledge that biological factors can predispose an individual to depression and that cases of depression caused by endocrine and neurological disorders point towards the existence of neurobiological pathways that are relevant to depression. For Moncrieff, there are only two possibilites: either depression is caused by a specific brain mechanism that produces depression in the same way that there is a specific process that produces Parkinson’s disease, or no specific brain mechanisms exist in depression.

In a 2022 commentary with colleagues, I wrote about different ways in which we can understand the involvement of biological factors in depression:

“A sharp and binary distinction between biological and psychological explanations is untenable in light of our best understanding of cognitive-affective science and neuroscience. Our minds are embodied, embedded, and enacted. The involvement of biological factors can take many different forms in explanations of depression: (i) biological dysfunctions (e.g. hypothyroidism, stroke, HPA axis abnormalities, etc); (ii) biological risk factors (e.g. genetic variants, inflammatory processes, etc), (iii) biological mechanisms (e.g. brain circuits involved in the regulation of mood).”

Depression isn’t one thing, nor is it a neurological disorder caused by a central neurological abnormality. It’s a heterogeneous syndrome with fuzzy boundaries with neighboring syndromes. It is not caused by a specific brain process in the same sense as Parkinson’s disease. Depression, however, like all psychological-behavioral phenomena, has a neurophysiological dimension. Depressed people have brains and bodies, and these bodily processes (along with life experiences) predispose people to depression and realize depressive states. Meaningful things can be said about these processes. The associations with neurobiology are neither diagnostically specific nor do they constitute an “essence,” but they do exist, and existing research already points towards many of them. More importantly, whether specific brain processes involved in depression can be identified is somewhat tangential to whether depression can be considered an illness, a psychopathological state, or even simply as a distressing-disabling extreme of human behavior for which medical treatments can be helpful.

Moncrieff believes that such considerations are “too vague to be testable.”

What exactly is too vague to be testable? Once we accept that the mind is embodied and that the brain must realize or mediate depression, the possibility that we can discern some of the ways in which the brain does so automatically follows. It is this possibility that I maintain. That is the general logical argument. The particular associations are a matter of empirical discovery. Moncrieff confuses the logical argument “the mind is embodied and that the brain must realize or mediate depression in some manner” to be an empirical hypothesis that should be disbelieved until proven to the contrary.

In fact, a considerable body of research literature exists showing various (transdiagnostic) associations with depression, with a partial list being:

HPA axis changes, as demonstrated via inadequate suppression of cortisol in DST

Elevated levels of inflammatory markers

Lower levels of BDNF

Shorter REM sleep latency

Reduced hippocampal volume

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex activity and connectivity changes

SNP-based heritability of 9%

Moncrieff’s response to this list is to say that a 2019 meta-analysis looking at prospective evidence for whether biomarkers explain depression onset and relapse/recurrence “debunks” these claims.

It is clear that Moncrieff is conflating separate issues:

Moncrieff is conflating the question of what strength of evidence is needed to conclusively establish the involvement of a particular risk factor/mechanism/pathway in depression with the question of what the totality of evidence available to us suggests about the role of that cause/mechanism/pathway. [As one example of this, see the literature on HPA axis abnormalities in depression that are associated with melancholic and psychotic features. Here’s my discussion of dexamethasone suppression test as a biomarker.]

Secondly, and more importantly, she is conflating the question of demonstrating that a particular, hypothesized neurobiological risk factor/mechanism/pathway is involved in depression with the question of whether neurobiological risk factors/mechanisms/pathways exist that can be acted upon and that can be discerned and identified.

Moncrieff seems to assume that an inability to demonstrate the prospective, predictive power of a biomarker in a meta-analytic fashion is sufficient to disregard available evidence from other methodologies, and she seems to assume that an inability to demonstrate prospective predictive power of a biomarker in a meta-analytic fashion is sufficient for us to infer that neurobiological causes/mechanisms/pathways do not even exist.

I mentioned above how Moncrieff conveniently switches the burden of proof when it suits her. With regards to antidepressant mechanisms, she writes:

“If you give someone with depression a dose of a mind-altering drug, like heroin, they would most likely feel less depressed for a while. Antidepressants are not the same as heroin, and the alterations they produce are usually quite subtle, but most of them numb or restrict emotions to some degree, which might reduce depression scores.

I am using ‘might’ here too, but this scenario needs to be ruled out before we can conclude that antidepressants ‘work’ by affecting a putative biological mechanism. The burden of proof needs to be on those who suggest that as well as their brain and mind-altering effects, antidepressants also target depression mechanisms.”

[It doesn’t seem coincidental that RFK Jr also brought up a comparison between antidepressants and heroin in his confirmation hearing.]

Moncrieff, of course, ignores that existing studies that have examined whether emotional blunting explains antidepressant benefits have not found support for the idea, and that we have other hypotheses that are better supported by available evidence. To even acknowledge in theory that there are brain mechanisms involved in depression, Moncrieff demands prospective, predictive meta-analytic evidence, but she wants us to treat her pet hypothesis that emotional blunting explains antidepressant benefits to be treated as the default explanation until it is conclusively ruled out!

Moncrieff asserts that decades of research have failed to provide evidence that serotonin is involved in mood or behavior (note: not just depression but mood and behavior in general!), and that all we can confidently say is that serotonin inhibits sexual behavior.

“It is not true, therefore, that we ‘know’ that serotonin is involved in mood or behaviour. In the book I describe how there is evidence that serotonin has a detrimental effect on sexual behaviour, but that is about all we can say about its behavioural functions.”

A laughable statement! You can consult any friendly neighborhood neuroscientist who studies these things. Neuroscientists will tell you that the relationship is far from straightforward, but available evidence demonstrates the involvement of the serotonin system in mood and behavior.

One doesn’t even have to dig deep to offer supporting evidence:

Salvan et al. 2023. Serotonin regulation of behavior via large-scale neuromodulation of serotonin receptor networks. Nature Neuroscience. The paper replicates and elaborates on serotonin’s effects on impulsivity and negative biases.

Colwell, et al. 2024. Direct serotonin release in humans shapes aversive learning and inhibition. Nature Communications. Reinforcement learning models reveal that increasing synaptic serotonin reduces sensitivity for outcomes in aversive contexts. Furthermore, increasing synaptic serotonin enhances behavioral inhibition, and shifts bias towards impulse control during exposure to aversive emotional probes.

Not only that, the findings of these studies also support one of the key hypotheses of the antidepressant mechanism of action: a shift in emotional information processing.

Moncrieff tries to hide behind the fact that there are sometimes inconsistencies in research findings, but instead of looking at the totality of evidence and converging lines of research results, she wants to deny that we can meaningfully say anything about serotonin and emotional behavior. Because if she did, she’d have to accept the implication that antidepressants can act on serotonergic pathways to produce beneficial effects even if there is no serotonin dysfunction (as one proposed mechanism among others).

What can be done?

Do what you can to expose this 3-step rhetorical strategy. Do not be swept away by the chaos and outrage generated by the process. To any sensible person who is willing to listen, outline and explain what is happening. Powerful forces are at work to enflame and exploit populist, anti-establishment sentiments in service of antipsychiatry.

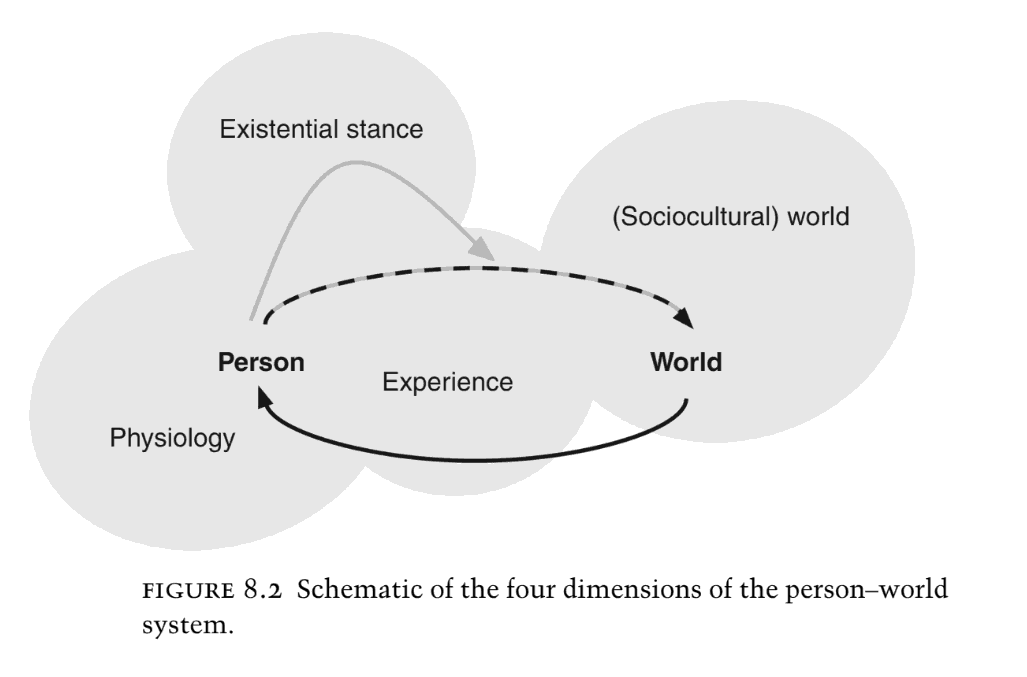

To accept embodied cognition is to accept that depression, like all behavioral states, has a neurobiological dimension. Furthermore, based on considerations such as the existence of “organic” cases of depression (i.e., depression caused by endocrine and neurological disorders or by medications such as interferon-alpha) and the existence of effective medical treatments, we can be confident that discernible neurobiological processes exist to some degree and meaningful things can be said about them, but the specifics will be a matter of empirical discovery. To say so does not constitute neurobiological reductionism, nor does it turn depression into a neurological disorder. Neurophysiology is simply one dimension of an enactive system.

Sanneke de Haan. Enactive Psychiatry (2020) As far as we can tell, depression is not caused by a serotonin dysfunction, but it remains an open question whether some forms of depression are characterized by serotonin abnormalities. We should not assume that such abnormalities exist until they are demonstrated.

Available evidence suggests that serotonin pathways are involved in mood and behavior, especially with regards to emotional information processing and behavioral inhibition, and this also ties in neatly with existing hypotheses of antidepressant mechanisms of action.

Rigorous systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of antidepressants show that antidepressants outperform placebo, that a single trial of an antidepressant produces large improvements in about 25% of patients overall (and 15% if you subtract placebo), with many others experiencing milder degrees of improvement. In practice, multiple trials of antidepressants are often needed. Studies suggest that with 2 trials of antidepressants, about 40% of patients experience large improvement. [See my discussion here of efficacy of antidepressants.]

The short-term efficacy of antidepressants is comparable to the short-term efficacy of psychotherapies in clinical trials, and the combination appears to be superior to either alone.

Far too many people are not helped by available antidepressants (or by available psychotherapies, for that matter). Hence the tremendous need for innovative treatments with new mechanisms.

Antidepressants indeed come with significant side effects, including serious withdrawal and sexual side effects, which is why clinical practice guidelines recommend prioritizing psychological and lifestyle interventions in mild to moderate cases of depression.

The medications known as “antidepressants” are clinically useful not just in the treatment of depression but in a wide range of conditions, such as anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia, etc. No argument against the general clinical utility of SSRIs can be made by looking at evidence from depression trials alone.

Depression can be approached and understood medically, but it can also be approached and understood through a variety of other psychological, existential, spiritual, and political frameworks. Recognizing depression as a medical condition does not mean rejecting the value of approaching and addressing depression via other perspectives.

Moncrieff says that she recognizes that some people have extreme emotional reactions that are out of the ordinary, but that this doesn’t make it a medical disorder. I say: what matters is not whether we call it a “medical disorder,” but whether we recognize that depression is an extreme reaction that is out of the ordinary, that it causes a tremendous amount of disability and that it is a source of distress and suffering, that it increases the risk of suicide and all-cause mortality, and worsens the outcomes of a wide range of physical health problems, that at least some depressed people are substantially helped by treatments such as medications, neurostimulation, and psychotherapies, and the possibility that various aspects of its neurobiology can be elucidated. Calling depression a medical disorder is simply a way of recognizing all this.

Moncrieff rejects the status of depression as a medical condition and denies the neurobiology of depression because she can conceptualize medicine and biology only in a reductive manner. In her mind, she is defending depressed individuals from being reduced to “walking representations of neurological mechanisms.” I agree with that goal but disagree that this requires denying the neurobiology of depression.

In conversations on social media, once in a while someone says something along the lines of, “Moncrieff is taking an extreme and absolutist stance, but a lot of what she says has some merit, and we should try to steelman her approach to see the value of her criticisms.” The problem is that Moncrieff herself has no interest in such steelmanning because it involves softening her rhetoric and making concessions she has no desire to make. This, in fact, applies to much of British critical psychiatry, represented by the critical psychiatry network. In a manner, I see my efforts to articulate the approach of “critical and integrative pluralism” as the outcome of steelmanning critical psychiatry arguments that are otherwise on shaky philosophical and scientific grounds. It is unfortunate that the critical psychiatry network has distanced itself from such efforts so far.

P.S. Another good example of the 3-step attack strategy I have outlined above is the attack campaign on electroconvulsive therapy by the British psychologist John Read and colleagues.

Step 1: Read et al. show in a 2020 review paper that ECT vs. sham-ECT trials are all old and low quality.

Step 2: They then pretend that they have shown that there is no evidence that ECT is effective, ignoring all other sources of evidence using other trial designs and ignoring the fact that the low-quality sham-ECT trials do actually show a large meta-analytic effect.

Step 3: And finally, they argue that given ECT’s “inefficacy” and its notable harms, ECT’s use should be immediately suspended.

Voila!

This is a somewhat belated note of thanks, Awais, for your detailed and meticulous debunking of a misleading and extreme thesis from "across the Pond." I also appreciate your call-out to the article Dr. George Dawson and I wrote, knocking down the false claim that antidepressants work by "numbing" emotions:

See: https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/antidepressants-do-not-work-by-numbing-emotions

The effort to discredit and disparage psychiatric medication has a long and ignoble history, and is now seen in the false claims by RFK Jr. as the recently appointed head of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. I discuss some historical aspects of the movement against psychiatric medication on the Psychiatric Times website.

https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/the-ongoing-movement-against-psychiatric-medications

None of this is to engage in cheer-leading for psychiatric medications--antidepressants in particular--whose risks and limitations are very well-known to those of us who have written about them and prescribed them for nearly our entire professional lives (my experience goes back over 40 years). We should always acknowledge that these agents--while safe and effective when carefully prescribed--are not panaceas, and ought to be used very conservatively as part of a comprehensive, bio-psycho-social approach to the patient.

Best regards,

Ron

Ronald W. Pies, MD

Whew! Thank you for the effort you've put into this and the clarity you bring to the underlying murk of it all. My work -- advocating for a more rigorous approach to including precise observations of actual subjective experience in studies of effects such as these -- currently sits far outside these contentious debates, but I can see what I might be getting myself into at some point. I'll definitely need some help if/when that day comes.