Makoto Fujimura

Interdependence of Colors

Art, Liberal Democracy, and the Culture of Seeing

A Talk for the Alliance of Responsible Citizens (ARC – UK) 20251

We begin our journey in the fractures.2

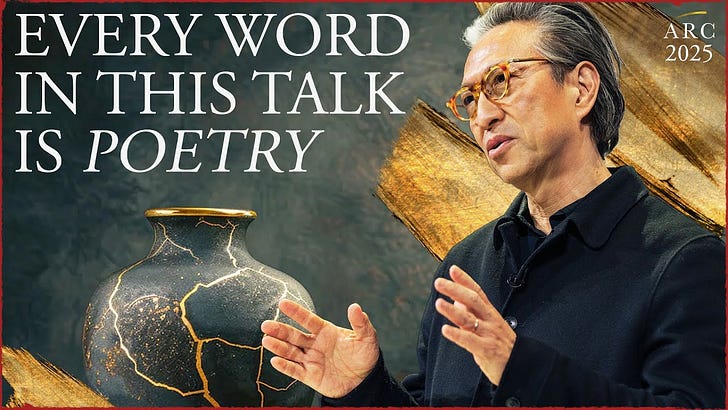

This Kintsugi bowl, which I referred to last year at ARC, carries more than gold (kin) in the fractures; it holds time, patience in the hands of a master beholding what is broken. When something shatters in Japan, traditionally, it is not discarded but honored and considered to be sacred. In the West, we are quick to throw away, to replace, to move on. But the Kintsugi master does not rush to repair. The first gesture is not fixing, but seeing—an act of reverence.

To mend is to behold. If we want to mend a culture and create a civilization worth living in, we need first to behold the fractures.

When Japan lacquer is poured into the broken seams, when the gold is dusted into the cracks, the vessel is not returned to its former state. It becomes something more — more luminous, more valuable, more whole not in spite of, but because of its wounds. The fissure lines become a horizon, a curvature of a sacred river, and a mountain ridge of gold.

Joseph Campbell famously said: “If you want to change culture, change the metaphor.” If we can learn to see the world this way—to see our brokenness not as an end, but as a beginning—then our fractures become the portal of generativity. But we need patience to behold. We may need to behold our tears first.

I turn to another tradition that embodies this slow seeing (moving from the “left” hemisphere or the brain to the right side): illuminated manuscripts. Here you see the Ormesby Psalter, the sacred calligraphy of medieval scriptoria, and, in my own work displayed in the gallery, The Four Holy Gospels—a project commissioned to mark the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible. (Go through Charis-Kairos (Grace Time), Matthew (Consider the Lilies), Mark (Water Flames), Luke (Prodigal God), John (In the Beginning))