Parking the Problem: NYC’s Missed Chance to Move Forward

How New York City’s watered-down zoning reforms keep parking mandates alive, delaying much-needed housing and community-centered development.

On Thursday, December 7th, New York City made the baffling decision to stubbornly continue to enforce car-centric parking mandates in its sprawling low-density neighborhoods.

Faced with the greatest housing vacancy and scarcity in decades, in addition to record levels of homelessness, New York City needed more housing fast. One of the biggest blockers to get the plan through was the massive debate around minimum parking requirements for new housing.

The City Council passed a watered down version of Mayor Eric Adams’ City of Yes plan with a 31–20 vote. A number of changes were made diluting the original proposal: creating parking mandate zones instead of eliminating parking mandates, prohibiting ADUs and adding restrictive guidelines for ADUs in many low density neighborhoods, and reducing transit oriented development (TODs) eligibility across low-density districts and along Metro Train stations.

By limiting a number of these zoning changes, particularly the parking mandate zones, the final proposal went from potentially providing over 109,000 homes to only 80,000 homes over the next 15 years. It also restricts these homes from being built in areas with more space, which would have shared the burden across more neighborhoods.

Instead, neighborhoods that have already been adding housing for years will continue to add more, while low-density neighborhoods that have not been adding housing, won’t.

Many council members that received concessions to help pass the plan still voted no such as folks like Kamillah Hanks, Jim Gennaro, and Chris Banks. Vehement opponents of the plan like Vickie Paladino and Bob Holden held fast and voted no as well.

Speaker Adrienne Adams was able to secure an additional $5 billion of capital funding — providing necessary funding for NYCHA repairs, more rental vouchers and additional infrastructure upgrades to address flooding, among other initiatives. And while this is helpful, it doesn’t get at the main goal of the City of Yes — to build “a little more housing in every neighborhood.”

Throughout the rest of this article, I want to focus on parking mandates and why it continues to be the biggest obstacle for more housing, decreased congestion, and general improvements to quality of life.

Decoding Parking Mandates

To understand the debate and the watered down changes, it’s important to first understand what parking mandates are.

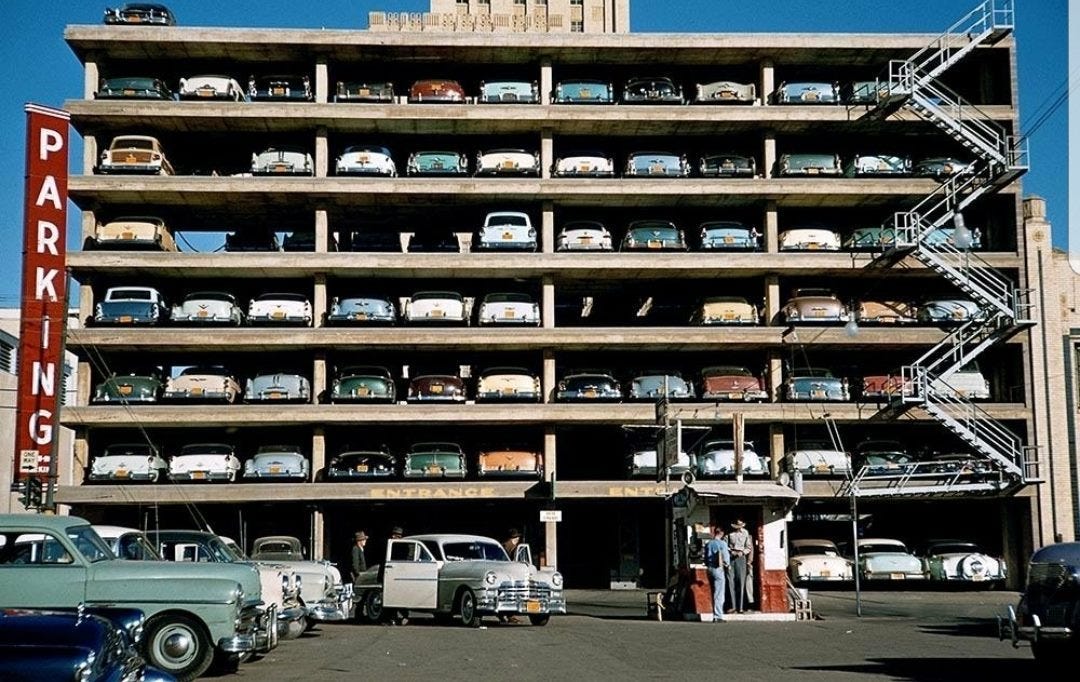

As cars grew more popular and affordable in the early 20th century, urban planners anticipated a car-centric future. They began requiring parking spaces in residential and commercial developments, ensuring that streets and buildings could accommodate the rising number of vehicles.

In 1961, New York City formalized parking mandates into law, shifting from a city that banned overnight street parking into one that embedded parking requirements into zoning regulations. This law continues to remain in effect today, mandating developers to provide off-street parking for new housing units. While this might seem manageable in sprawling cities, it creates significant challenges in space-constrained environments like New York.

There is also little evidence to support the idea that parking mandates are necessary to ensure adequate parking availability. In fact, numerous studies suggest that the market itself can provide sufficient parking without government-imposed requirements. When parking is left to market forces, supply naturally adjusts to meet demand, as developers and property owners respond to the needs of the community.

The fear urban planners had before about not having enough parking spaces simply was not entirely justified nor a necessary requirement. Instead, this minimum requirement has only led to an overbuilding of parking that leads to wasted space and unnecessary costs, while underutilized spaces remain vacant.

Reducing parking also reduces car ownership, leading to increased investment in public transportation, decreased congestion and noise pollution, and improvements to overall community health.

Complicating Parking Rules Even More

The rules for parking are complex, with required parking spaces varying based on factors like zoning type, building use, and affordability. For instance, requirements differ between residential and commercial districts, mixed-use buildings, or affordable housing projects, creating a patchwork of regulations developers must navigate.

Typically, each dwelling unit requires at least one off-street parking space, whether one uses it or not. Higher rise buildings can reduce this down to 40% in a group parking facility and smaller lots less than 15,000 sq. ft. can also get a reduction down to 20%.

Other major cities like Minneapolis, San Francisco, and Seattle also had incredibly confusing parking mandate requirements. And so to simplify the requirements and open up the space for other purposes including building more housing, these cities eliminated parking mandates.

They have also proven that there has not been a significant parking shortage, further demonstrating that the market, rather than mandates, can effectively address parking needs.

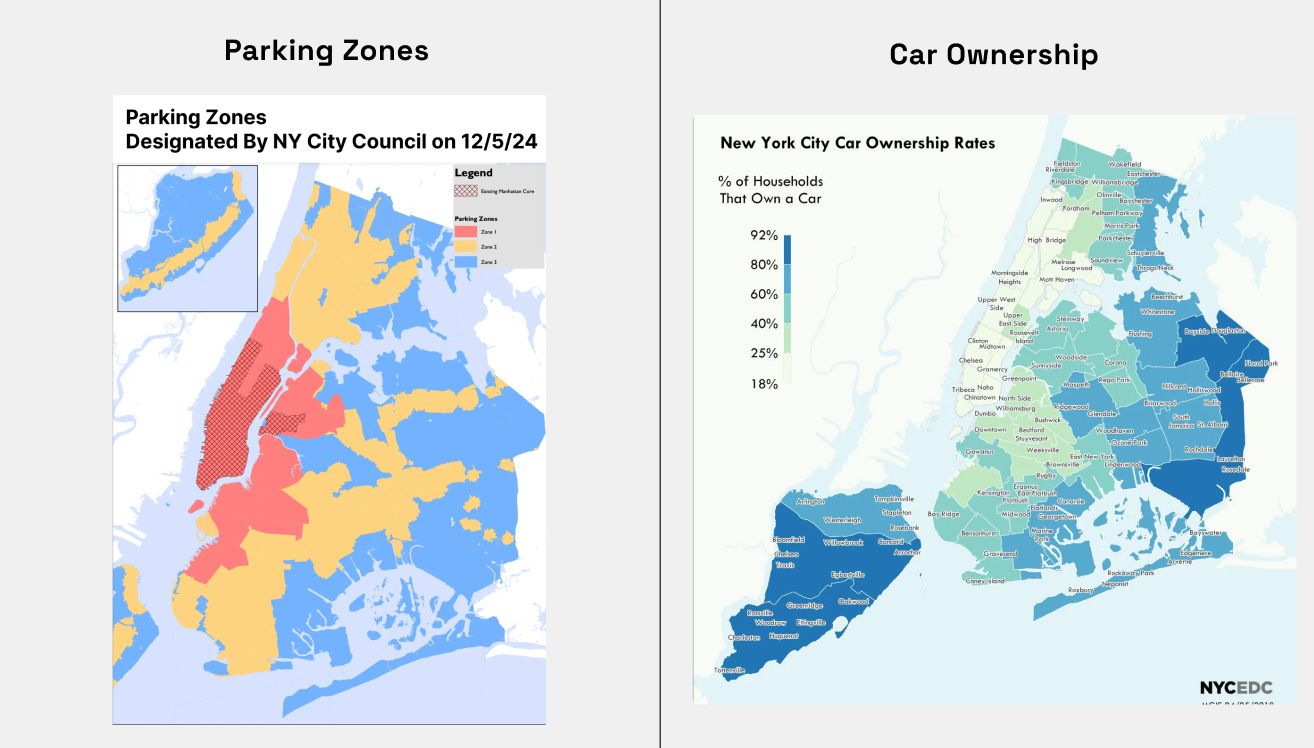

But in New York City this past month, the Land Use Committee instead passed a more complicated tiered parking mandate zone separated into three categories.

Zone 1 — No parking mandates: “Eliminating residential parking requirements for new developments.”

Zone 2 — Reducing parking mandates: “Significant reduction in multi-family residential parking requirements.”

Zone 3 — Maintain the status quo: “Keep most parking requirements.”

ADUs, conversions, and TOD development housing did, however, become exempt from parking requirements across all zones, while affordable housing and Town Center developments still had requirements. This is great, except many low density areas that could build more of these units are restricted from building them.

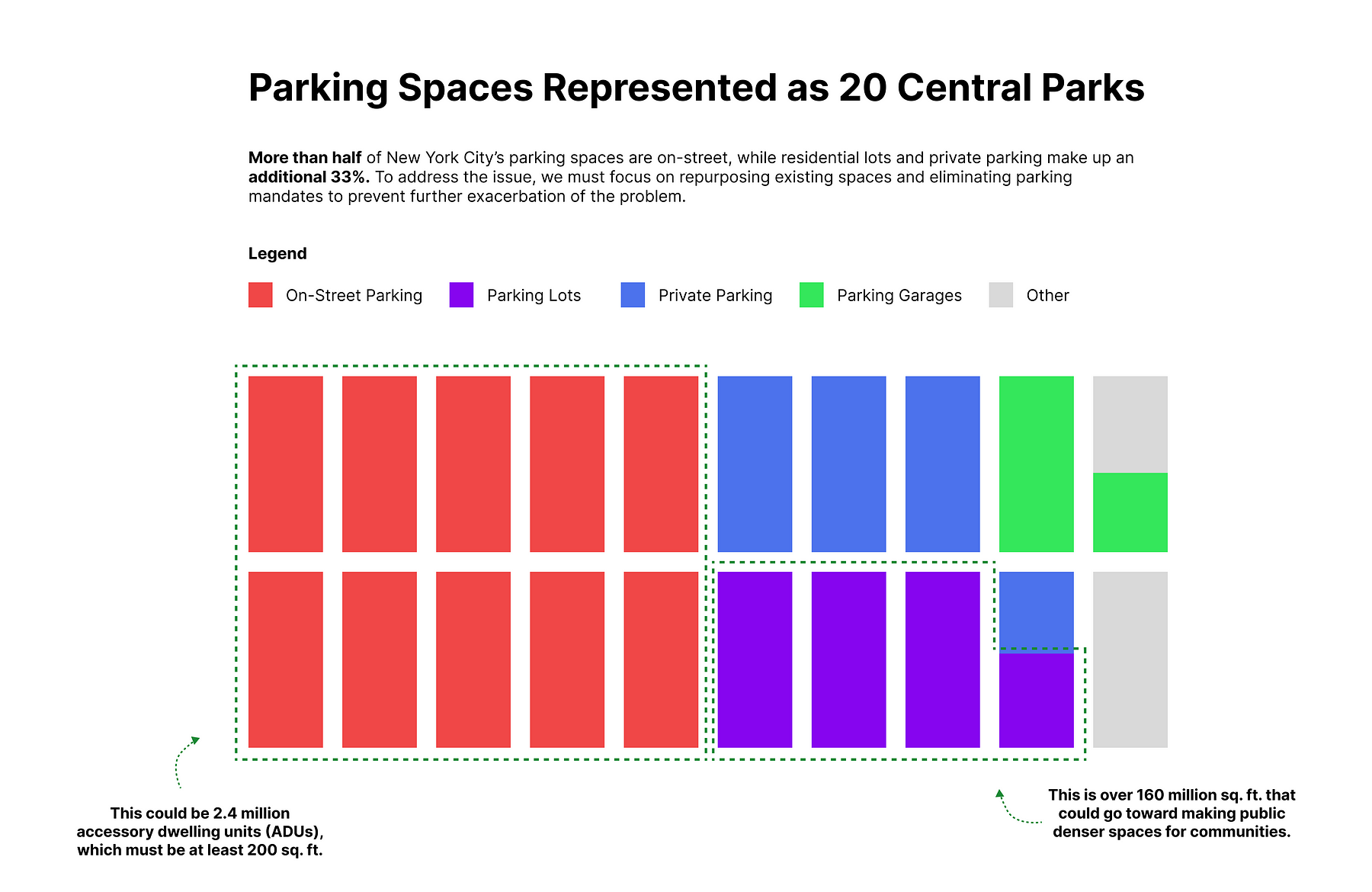

New York City is home to an estimated 5.4 million parking spaces — nearly one for each of the city’s 5.6 million licensed drivers. If each space measures the typical 8 by 20 feet, that adds up to an astonishing 860 million square feet, equivalent to over 20 Central Parks. This doesn’t even include the amount of additional 4to 6 ft. of space a car needs to turn into a parking space.

A breakdown from an internal 2016 investigation into parking signs and blockfaces reveals that about 3 million of these spaces are curbside on-street parking. Additionally, parking garages account for 390,000 spots, surface lots provide around 1 million, and private parking contributes over 1 million spaces.

Amazingly, this estimate likely underrepresents the true number of parking spaces in the city. Drivers often park in areas that aren’t officially designated, and there’s limited data on private parking garages and driveways, making it hard to account for the full extent of space dedicated to cars.

Reimagining Parking Spaces

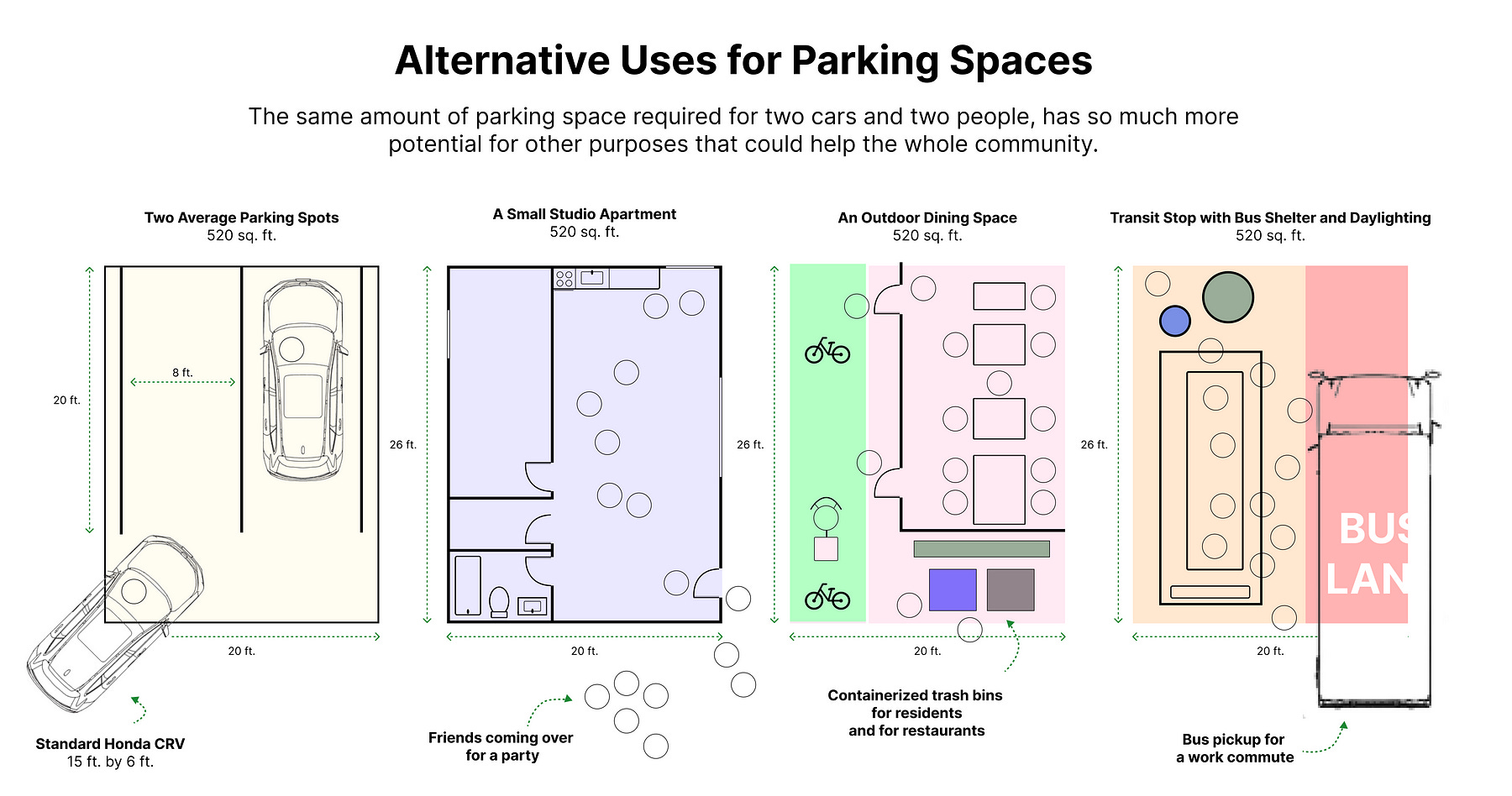

Eliminating parking mandates not only allows for more housing but also unlocks a range of opportunities for alternative uses.

The NYC DOT has proposed several innovative ideas for repurposing on-street parking to enhance community spaces and improve quality of life.

Instead, that space could become more flexible and active, prioritizing transit boarding, pickups/drop-offs, and freight activities. It could also be designated for people and local businesses to provide service through plazas or outdoor dining. Waste containers, green infrastructure, bike lanes, daylighting, or even film production can find purpose by the curb.

Two parking spot spaces should be for more than just two people and cars. Two parking spots can make up one studio apartment. Two parking spots can create outdoor dining space for cafes and restaurants, with room for waste containers. Two parking spots can provide room for a bus shelter, bus pickup, and daylighting.

Without parking lots and garages, we can create more parks, community centers, and local businesses. This shift fosters vibrant, community-focused spaces that benefit everyone.

Manhattan alone saw much of the air quality benefits with an elimination of parking minimums due to the Clean Air Act in 1982. There is a reduced amount of congestion with the average level of carbon monoxide dropping gradually since then.

This doesn’t mean we should eliminate all parking. Reducing the amount of parking encourages fewer people to drive, freeing up more parking spaces for those who need them, such as workers or individuals with disabilities.

Let’s take a look at London as a case study. They abolished parking minimums since 2004 and have seen massive benefits as a result. The number of parking spaces provided dropped around 40% leading to a total of over 143,000 parking spaces.

Ironically, the market did continue to provide more parking with higher density, as well as increased transit, which proves that the opposite direction is also necessary. Parking caps also do not cause spillover with on-street parking congestion. Instead, that must be addressed through parking permits or better priced parking meters — not minimum parking requirements.

A Crossroads Moment

By now, you’re likely as frustrated as I am with the City Council’s missed opportunity to eliminate parking mandates.

Many of these same council members have voted on related issues, such as outdoor dining and the upcoming e-bike licensing law, which prioritize cars over the safety and needs of people.

33% of city council that is running next election voted NO on the City of Yes.

18% of city council that is running next election voted NO on outdoor dining.

49% of city council that is running next election is SPONSORING e-bike licensing.

There is action you can take — by protesting and voting in the upcoming June 25, 2025 election.

Check to see how your council members voted and use this information to hold them accountable. Research the rest of the field and their stances on these same policies, so you can help make the right choice and make this city a better place for New Yorkers.