0. Introduction

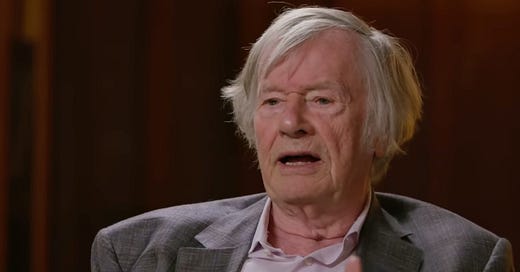

Stoicism, skepticism and Epicureanism are known together as Hellenistic philosophy. And what I find most compelling about these schools is their focus on the good life. Modern philosophy so often veers into useless speculation and pointless questions about meaningless things, but Hellenistic philosophy is just laser focused on happiness. How can I be happy? How can I live a worthwhile life? These are the kinds of practical questions that Hellenistic philosophy bothers itself with. My guest today is a pioneer of the field, the legendary Anthony Long. Professor Long will teach us what happiness consists of for each of these Hellenistic schools. And I think the most surprising insight I took away is how the very things we despair of, the ancients think bring about happiness. So, for example, atomism, right? This idea that the world is nothing but atoms buzzing in the void, it creates great distress for many people today.

But the Epicureans prescribe atomism to free people from the worry of divine punishment. So for them, materialism is not a cause of nihilism, as it is for us, but it's a cause of happiness. Now, another one of these crazy 180s is how the skeptics believed that a foundational doubt, right, a fundamental suspension of judgment on the most important questions about the world is not a hindrance to, but the secret to happiness. What I loved about all of these odd proposals for the good life is how they've challenged my own fundamental assumptions I held around happiness, and I hope they'll do the same for you.

1. What Is Hellenistic Philosophy

Johnathan Bi: Could you tell us a bit about what Hellenistic philosophy is?

Anthony Long: Hellenistic philosophy developed after the death of Aristotle in, not just in Athens, but in other parts of the Mediterranean world. Hellenistic is just a modern term of art, to capture this sense of a Greek civilization that had spread far and wide, you know, into Egypt, the south, into the east, where we call Turkey today. We should talk about Hellenistic philosophies, because although the ones we'll be talking about are Stoicism, skepticism, Epicureanism, Pyrrhonism, there were others besides. It was an extraordinary time. It was probably the period in the history of the world when philosophy was sort of most diffused, partly because it covered what we might call today higher education, but also because the philosophies were always competing with one another. And part of what makes the period exciting and philosophically rich is challenges.

I mean, so hedonism on the one hand, Stoicism on the other, are very much at loggerheads with each other, the skeptics denying that anything can be firmly known. Stoicism and Epicureanism both are arguing that they are a criteria of truth, we can establish things for certain. And so we have this very rich period. But unfortunately, it's a little bit like the tip of an iceberg because most of what was written at that time has perished. Whereas we have the works of Plato and Aristotle, Stoicism and Epicureanism and the other Hellenistic philosophies are mainly recovered in sort of quotations and summaries. And so part of what's been exciting for me and others like me who work on this is trying to reconstruct the arguments and doctrines which were, you know, are not available to us in a full sense.

Johnathan Bi: One uniting theme among the three schools seem to be that they offer competing answers to the question how do we live the good life, eudaimonia. So can you tell us a bit about this goal?

Anthony Long: Yes, I mean, I think the starting point here is probably to go right back to Socrates. Early Greek science had not much to do with how to live. Socrates was the figure, the Athenian figure who, you know, as this sort of street philosopher who would like to challenge people and ask what they thought about things and really sort of put on the map the idea that there is something we could call a good life, which was something that could be rationally examined and argued for. And so Socrates, of course, was not a... No kind of dogmatist. He'll try out the idea of hedonism as a philosophy or skepticism. I mean, a lot of what become the Hellenistic philosophies have their kind of roots and embryo in Socratic ideas. Philosophy could become a kind of guide to living. And so with the catchword being this word, eudaimonia. Eudaimonia, meaning literally having your sort of divinity in a good shape, but it turns out to be sort of best understood as something like a successful life.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Anthony Long: I think, I say successful because one doesn't want to moralize it too much. It's a good life, but it doesn't mean good in a kind of purely Kantian ethical sense.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Anthony Long: A life in which you feel, you know, your own life would be described by other people as well as yourself as, you know, having been worthwhile.

Johnathan Bi: Right. Flourishing.

Anthony Long: Flourishing.

Johnathan Bi: Well lived.

Anthony Long: Flourishing. Well, yeah.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Anthony Long: Wellbeing as often translated.

Johnathan Bi: Let me give you a quote from your book:

The influence of Plato and Aristotle has proved to be more profound and persistent, but in the widest sense less pervasive. Everyone has some notion of what it means to be stoic, skeptical and epicurean.

(Anthony Long, Hellenistic Philosophy)

What I think is very interesting is, we have a notion of what it means to be these three things because we think about them primarily as ethics, as philosophy of ethics.

Anthony Long: Yes.

Johnathan Bi: But in your book, you actually argue that that's a misconception, that ethics isn't the only or maybe even sole focus of these schools.

Anthony Long: Yeah, that's exactly right. Epicureanism and Stoicism have a kind of comprehensive outlook on the world. I mean, they involve science, they involve, especially in case of Stoics, they involve a very great deal of logic. Logic, which, you know, can be applied to how to live, but logical theorems and propositional calculus, and all those kind of notions are things we would like to study for their own sake. The Stoics would argue, of course, that really what you're trying to do as a Stoic is you're trying to maximize your potential as a rational being. And, of course, mathematics, logic come into that centrally.

And so, but I think what's special about Hellenistic philosophy, although of course you've got the vestiges of it already in Aristotle and Plato, is the idea that you're sort of choosing a particular set of goals and strategies to make your life worthwhile, you know, at all times. I mean, it's a much broader conception of the good life than Aristotle. Aristotle has, you know, thinks of contemplation, studying metaphysics, studying the sciences, those are all very worthwhile things, but he doesn't package them together as part of ethics. Aristotle sort of thinks of his curriculum as quite detachable. I mean, you've got the parts of animals, you've got the study of plants. And so he's beginning to kind of compartmentalize study, whereas at some level, Epicureanism, Stoicism have a kind of comprehensive package.

Johnathan Bi: I see. So maybe this is another way of what you're trying to say, which is that for Aristotle, even though he recognizes the virtue of contemplation to be one of the highest virtues and to be a possible foundation of a good life, it's not that you have to study his physics or the biology that he does.

Anthony Long: Right.

Johnathan Bi: Whereas what's unique about these three schools is that their logic and their physics, studying them is constitutive to the good life.

Anthony Long: Yes. That's right.

Johnathan Bi: So even though they are not ethics only or ethics central, the ethics is first philosophy, maybe we can put it that way. Ethics is first philosophy in the sense that it leads to why the metaphysics and the logics and the physics is important.

Anthony Long: Yes, I think that's right, since we're talking about comparing Plato and Aristotle and help us to get a sense of what Hellenistic philosophy is all about. One aspect of Aristotle, of course, which is central, is the notion that his philosophy, especially his ethics, is designed for the small polis community.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Anthony Long: And Aristotle thought that an ideal community should be quite small, people should almost be... Everybody should know each other. And the Hellenistic world, of course, with the diffusion of Greek culture after Alexander the Great's conquests, then develops a much more cosmopolitan outlook. And that's particularly important for Stoicism, I think.

Johnathan Bi: Right. And let me give you a quote on your book that I think captures this point.

The early Stoics, Skeptics, and Epicureans were supremely confident that a man's inner resources, his rationality, can provide the only firm basis for a happy and tranquil life. The city recedes into the background, and this is a sign of the times.

(Anthony Long, Hellenistic Philosophy)

Anthony Long: Yes.

Johnathan Bi: So compared to Plato and Aristotle, the idea is that the ethics is no longer polis driven. It does become cosmopolitan in the sense that you say, but in the same move, it also turns more inward as well.

Anthony Long: Yes, I think that's exactly right. So, yes, the notion of the inner life, which is, I mean, has a huge bearing, of course, upon how you behave in the world.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Anthony Long: But you are... There is a kind of introspective aspect to it. And the way Epictetus begins his very first essay where he says, there's only one craft that can not only study a field like, say, music or cobbling, but can also examine itself, and that's reason. And reason in Stoicism is also something like the self, the conscious self. It is what you are in your own introspective, reflective, dialogical mode.

Johnathan Bi: Right. Let me ask one last question before we actually dive into each of these three schools, which is what are the geopolitical, socio-historical backdrop, and what is the circumstance behind the Hellenistic era that led to this ethics elevation as first philosophy, including this cosmopolitan turn?

Anthony Long: Okay, good. Yeah. When I started my work, there was a kind of cliche that Stoicism, Epicureanism especially, perhaps Cynicism too, were sort of, they were back to the wall kind of philosophies, that the polis had lost its rationale.

Johnathan Bi: Alexander had conquered the known world. Right.

Anthony Long: Yes. And people were lost and desperate of, for some kind of foundation. I think that's not true. I think if you look at the life of Zeno and what we know about Epicurus, they were living in a very prosperous time. The Hellenistic world actually was quite prosperous. So although there's no doubt at all that these are philosophies which offer in some sense some kind of what you might call salvation, but it's not because the outer world was all, had gone to hell.

Johnathan Bi: Right.

Anthony Long: It's rather an additive. But at the same time, the interest in politics for its own sake, I mean the kind of books like Plato's Republic, Aristotle's Politics, philosophers are not writing those kind of books now. It's as if they're much more interested in a kind of ecumenical, I think ecumenical with a way the word to use, you know, they're interested in society, but they're interested in society not so much in a power politics sense as just, you know, the, how to organize your families, how to organize your friendships, these notions.

Johnathan Bi: Right. So you mentioned what sociopolitical forces did not influence Hellenistic philosophy, right? Clearing the ground. But is there something to be said about the actual real historical changes that led to these philosophies? Or should we read the philosophies as sprouting merely on the ideas level?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Johnathan Bi to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.