Listen to the radio version here.

I love, or at least like, just about every bird, but I must admit to some serious prejudice against anything that hurts chickadees, so one might reasonably guess that I wouldn’t like shrikes, songbirds specifically designed for killing tiny birds. But no, I find something about these handsome, feisty predators very appealing.

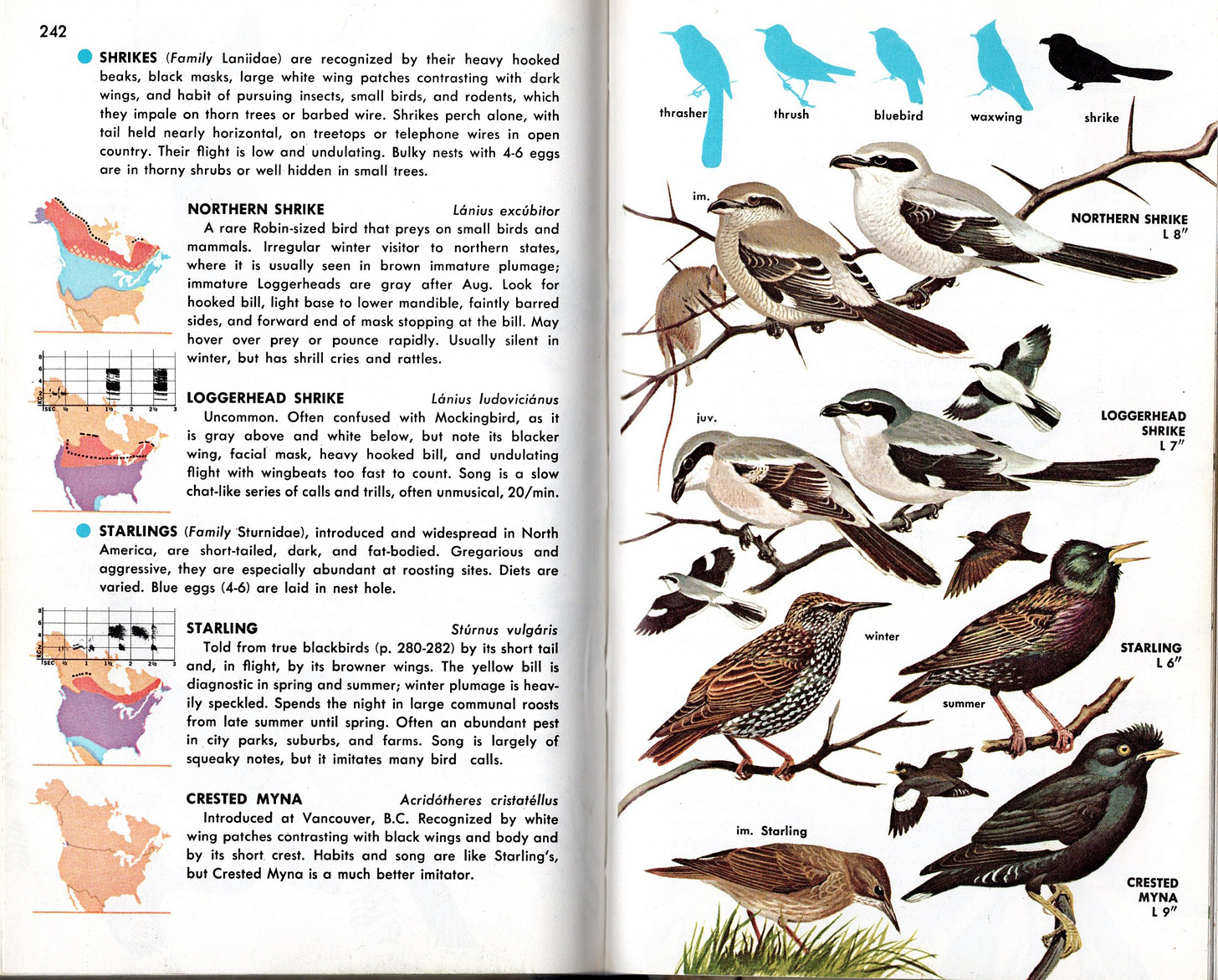

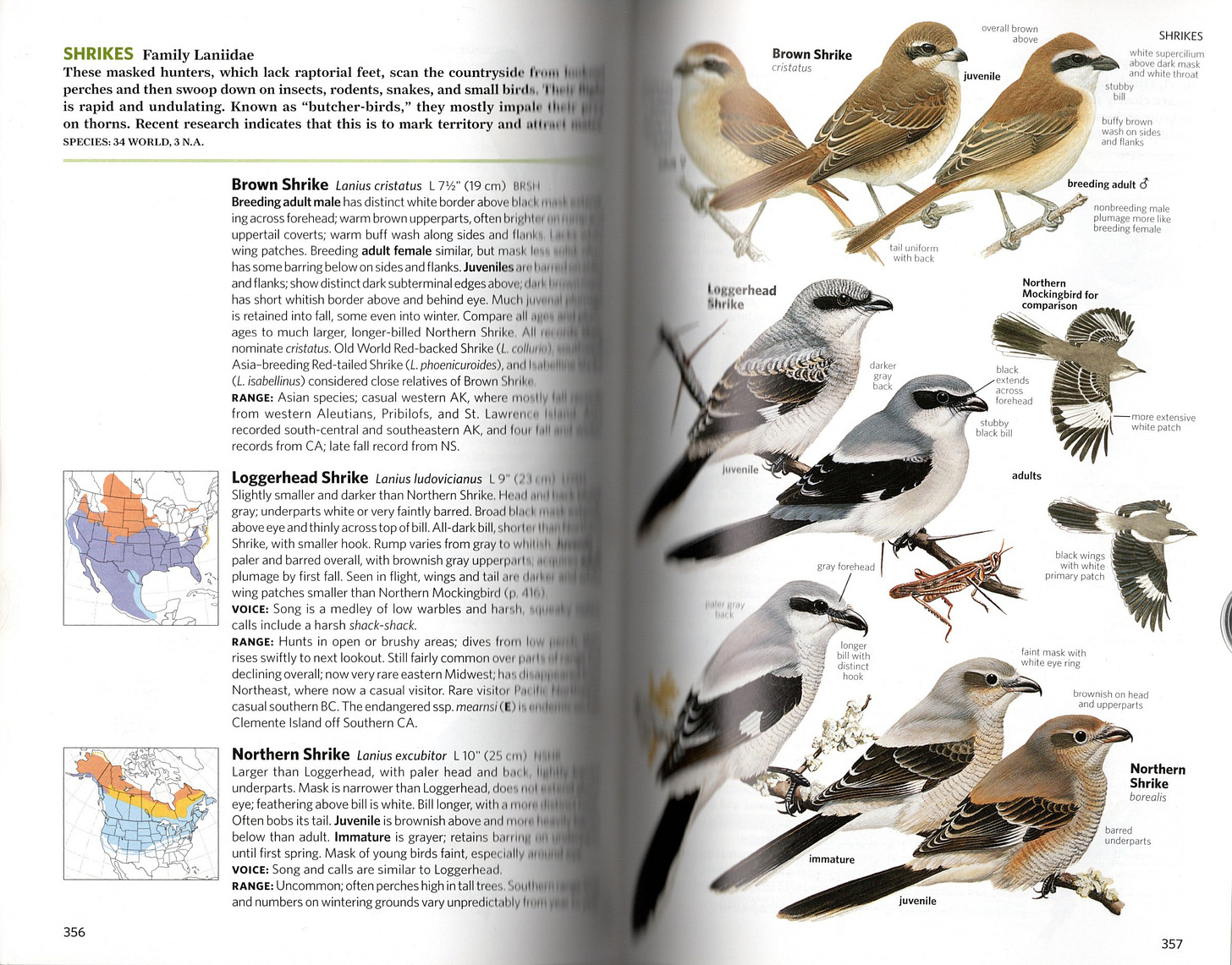

We see two different species of shrikes in the Upper Midwest.

The Northern Shrike breeds in the far north and visits us only in winter.

I have a strong preference for the smaller, daintier Loggerhead Shrike, once a common breeding bird in southern Minnesota and Wisconsin but whose numbers have dwindled dramatically throughout its range. Except for one individual I saw in Sauk County, Wisconsin, back in 1977, and a couple in Colorado in 2013, all the Loggerhead Shrikes I’ve seen so far have been in Mexico, California, Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Texas, Georgia, and Florida, all south of the range of Black-capped Chickadees. When I’ve found a barbed wire fence or thorny plant used as a Loggerhead Shrike’s meat locker, or seen a Loggerhead Shrike eating prey, the food items have run heavily to cold-blooded animals, especially large grasshoppers and small lizards. That I can handle. Meanwhile, twice over the years, I’ve seen a Northern Shrike eating one of my own backyard chickadees. I take that personally.

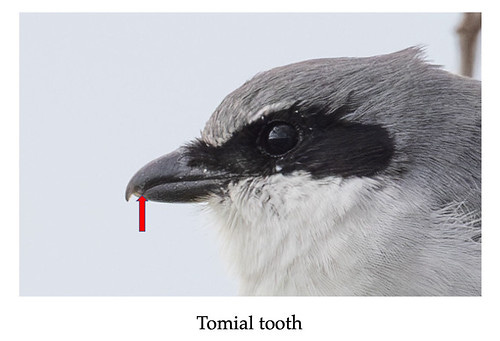

Shrikes are true songbirds, smaller than robins, with wimpy perching feet, not talons, yet they can take prey fully as large as themselves. For their own sake, they must kill their prey quickly to avoid being injured themselves. Convergent evolution with falcons equips them with a “tomial tooth,” a tiny notch and sharp projection on either side of the sharp upper bill-tip—the three points clamping down on the nape of a prey animal provide a quick death.

Loggerhead Shrikes feed on some prey too toxic for most predators, including monarch butterflies and eastern narrow-mouthed toads. They don’t eat these right away but impale them and wait a few days, eating them after the toxins break down.

Like monarchs, the huge, beautiful lubber grasshoppers of the Southeast apparently use their bright colors to warn predators away.

Loggerhead Shrikes are their only avian predator, and they can eat them immediately, devouring the head and abdomen while discarding the toxic thorax.

Although it’s likely the Loggerhead Shrike was never common in the northern third of either Wisconsin or Minnesota, my early field guides show it ranging well into both states.

In the southern part of both states, it was once quite common. In 1926, Thomas Sadler Roberts took a 12-day, 500-mile road trip moseying here and there in southwestern Minnesota and counted 89 Loggerhead Shrikes—something birders today could only dream of. During my lifetime it's declined throughout its range, and in 1972, Audubon placed it on their Blue List to draw attention to its plight. It’s now considered Near Threatened throughout its range and listed as Endangered in Wisconsin and Minnesota. (Here are links to Wisconsin’s Endangered Species list and Minnesota’s Endangered Species List.)

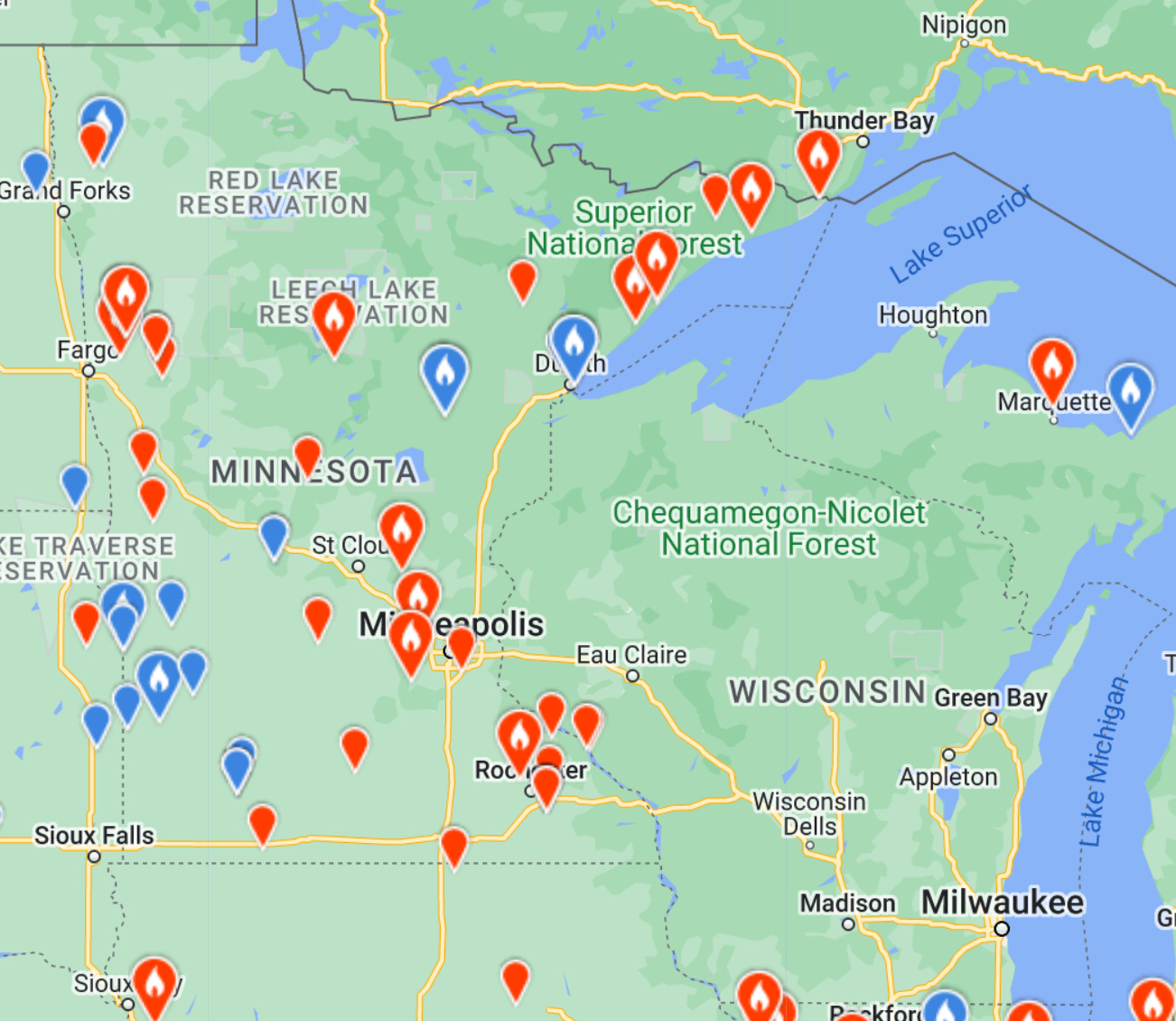

But for some inexplicable reason, Loggerhead Shrikes have been appearing here and there in even the northern parts of both states this year. This spring, several birders spotted them in Duluth and along the North Shore up to the Canadian border, and in the Sax-Zim Bog. Just this past weekend, some sharp-eyed birders found one in Ashland County, Wisconsin, and my friend Erik Bruhnke reported one in the Bog, so there’s a possibility some may be breeding up here.

I visit Florida a lot, mostly to see my son in Orlando, and get to enjoy Loggerhead Shrikes every time, usually in orange groves and other agricultural tracts and in more natural spaces, but occasionally even in theme parks. Unlike many South Florida species, Loggerhead Shrikes are extremely rare in the Florida Keys and not found in Cuba or other Caribbean islands.

When I was in South Florida in April both this year and last, I saw them in several places on the mainland, often in pairs or family groups.

The fledglings are curious and winsome. They’re reported to engage in playacting and practicing the kinds of hunting and impaling activities they’ll need to perfect to survive.

On Saturday, one birder I encountered in northern Wisconsin while looking for the caracara told me he’d seen a shrike about a mile away. I looked on my way home but missed it. I haven’t been to the bog yet this spring but am hoping to bird there this weekend, and I’ll sure be on the lookout. Chickadees justifiably fear them, but then again, plenty of innocent little caterpillars consider chickadees to be vicious serial killers.

Your communication skills are wonderful. Each and every post is so well done. Thank you!

I saw a Loggerhead Shrike in my backyard a few weeks ago. VERY rare in Maine but there’s another (or possibly same one?) being seen in midcoast Maine now so maybe they’ll become less of a rarity.