I have argued that very low fertility in high income countries is due to low marriage rates.

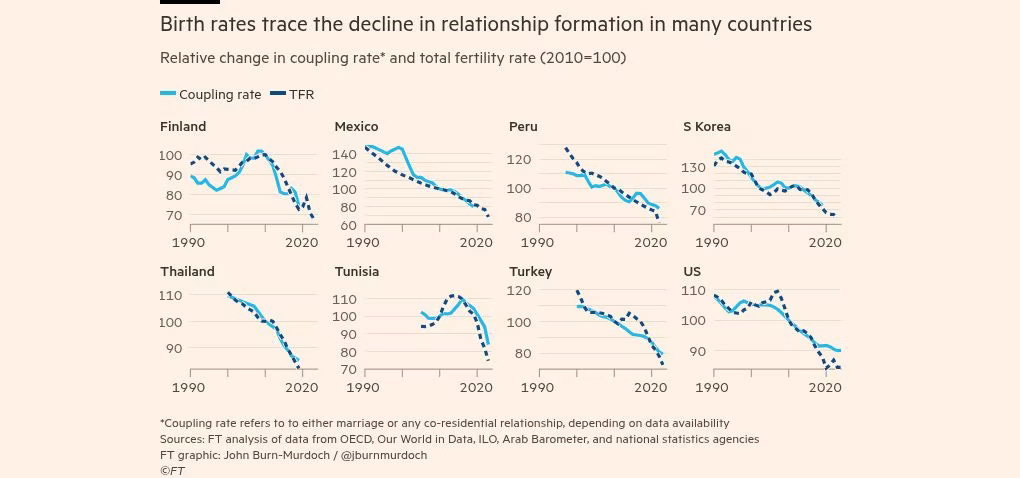

has a great article out yesterday at the FT reinforcing this argument: marriage and fertility rates move together with extraordinary regularity:That raises two huge questions:

Why are marriage rates low and falling?

What can we do to increase them?

This post will make basically two arguments.

1. The biggest reason marriage is falling is male economic underperformance.

2. While we try to find solutions for that issue, in the meantime, marriage subsidies work very well.

1. When Men Lose, Marriage Falls

In his piece,

emphasizes social media and the rise of values related to singleness as a source of falling marriage. That’s not crazy and I think there’s a lot of truth to it. But it also raises another question: Why were those values persuasive? Why was it that suddenly singleness was a lot more appealing?If you talk to young women today, they will almost uniformly tell you the same reason: dudes suck. The men are not good. Pickings are slim.

Now,

has a nice recent piece suggesting that women thinking dudes suck may actually be a deep human universal, and I think there’s some truth to that. But I also think there’s something else really important to realize, and that is that, quite frankly, the dudes really are not okay.Let’s take women at their word that even women who earnestly want to be married simply cannot find suitable men. Why not?

1.1 Men Are Insurance Policies

Well, without belaboring a point too much, let’s assume that one of the main things women want in a marriage partner is an economic support and backstop. That doesn’t mean women don’t want to work or want to be economic dependents! But most women plan to have kids, kids create huge work interruptions especially if the childbirth is medically complicated, women tend to be expected to and also to prefer to be primary caretakers for kids, and none of this is some big secret. Women know that having kids will create a big negative income shock at the exact moment they need more money for the aforementioned kid. So they want spouses who can help with consumption smoothing during that episode, and ensure that their children don’t suffer during any other periods of disemployment or economic weakness.

Evolutionarily speaking, men are basically insurance policies women use to ensure their children have stable consumption paths.

Note that this isn’t just “men are providers.” In fact, before industrialization, women almost all worked in roles similar to what men did. In hunter-gatherer societies, women produced a huge amount of the total calorie consumption for their communities. In the ancestral environment, women are not day-in-day-out dependent on men for “provision,” rather, women are are episodically dependent on men, and men especially operate as insurance policies against local resource shortages, protein deficiencies and, crucially, out-group violence. Today, the exact needs differ, but men are still basically insurance policies.

This isn’t to say men are only insurance policies. Also companions, friends, parents, any number of things. But the point is that most men can be befriended; most men can learn to be decent dads; most men will learn to be devoted lovers to a sufficiently interested women— these traits are not invariant, but for the median woman they are costly to discern and their level of variation is somewhat suppressed. But ability to provide insurance goods can be relatively easily assessed, and is extremely high-variance.

1.2 Men’s Incomes Predict Marriage

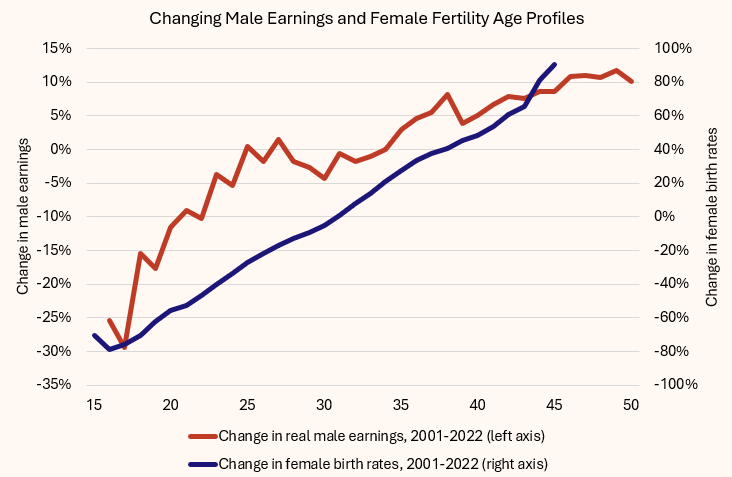

Here’s a graph of change in men’s income in the U.S. by age of men, vs. women’s fertility rates by age.

People talk a lot about falling teen births— they also sometimes mention the fact that teenagers aren’t working in jobs as much as in the past. Less noted is that, between 2001 and 2022, men’s real earnings showed zero growth or even decline at almost all ages below 35.

Young men are getting poorer.

This doesn’t mean Americans in general are getting poorer. They aren’t! American income is rising! But this rise is driven entirely by women and/or people 40+, not men. This means that on the crucial test of marriagability, men are falling behind: their ability to provide insurance coverage is not just not rising, it’s literally falling in inflation-adjusted terms!

Men over 35 have rising incomes. Women over 35 have rising birth rates.

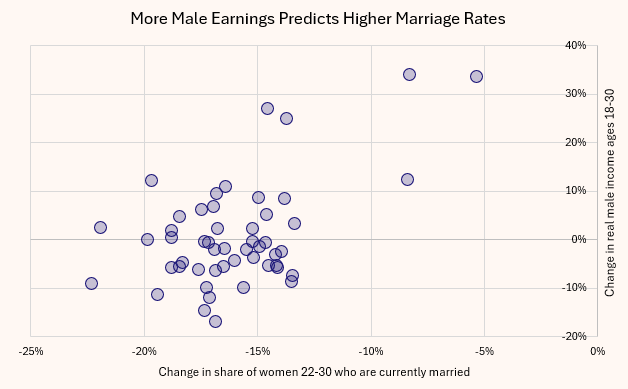

Maybe you think that’s a coincidence! Okay, here’s change in real personal income of 18-30 year old men 2000-2003 to 2020-2023 by U.S. state, compared to change in the share of 22-30 year old women who are married by state:

This is a very simple correlation, it’s not crazy strong— but still, it’s clear where men earn more, marriage rates are a bit higher! Panel models don’t produce as fun of graphs, but, indeed, with time controls included, there’s a significant, positive linkage between male incomes and female marriage rates in the 20s. When male earnings rise, female marriage rates rise somewhat. Female earnings have no clear positive or negative effect in the same panel model, and the male-female earnings gap also has no clear positive or negative effect.

Unfortunately, I don’t have a big harmonized database of income-by-age and marriage-by-age around the world to more formally test this hypothesis everywhere. I hope somebody else can do it. In the handful of countries I could check, it does look like young men have had uniquely bad earnings trajectories.

Now, note that there are possibly some exceptions. The fracking boom probably didn’t boost marriage, even though coal booms did. The likeliest explanation for this is basically the strange social dynamics of man-camps. Oil booms create counties with imbalanced sex ratios: tons of young men, few young women. As a result, local marriage effects may be suppressed. The scenario for men’s income boosting marriage is something which creates broad-based growth in young male income, not which uniquely concentrates men away from women.

1.3 Men’s Wealth Causes Marriage

We also basically know this effect is causal, because we have data from random lotteries! When women win the lottery, there is little to no effect on their marriage rates. But when men when the lottery, they get married. Seriously, they (buy homes and) get married. Even in Taiwan, they get married.

When men are wealthier, they are more attractive, and so women marry them, which means men’s and women’s marriage rates rise.

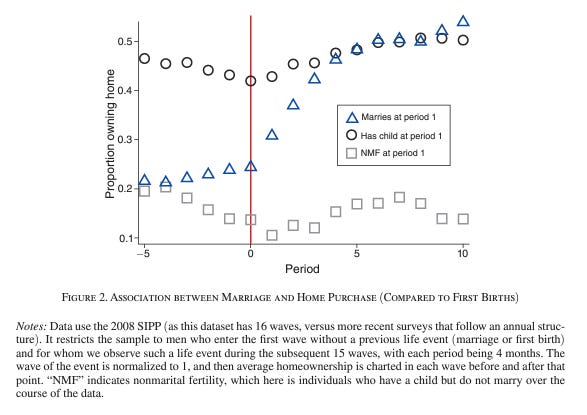

We also know that entrance into marriage for men is wildly strongly related to entrance into homeownership.

Homeownership is an additional kind of economic insurance product. Homeownership can subsidize future consumption smoothing via HELOCs, homeownership can build wealth, and homeownership is a reasonable signal of creditworthiness and earning power. This reaffirms the extent to which marriage is regulated by insurance-like dynamics. Women are not looking for “providers” per se: most women are able, in normal times, to “provide” for themselves and even their children. Rather, the key economic differentiator which drives selection of men for mating is their role as an “insurer.” Wealth and income uncorrelated with her labor force participation is a very valuable insurance product.

1.4 Other Explanations Matter, But Depend on Income

Changes in male income are not the only variable that matters. I agree with

, or with , that social media has also been a vector for a rapid, radical change in mating and relationship values and expectations. Men are increasingly hooked on porn which probably does not make them better marriage candidates, even as women are hooked on deceptively idealized and unobtainable visions of a free, luxurious, pampered single girl life. Likewise, the deep-seated change caused by the sexual revolution matters too: a key reason young people pursued marriage in the past was to have licit and frequent access to sex. That’s not needed anymore; nonmarital sex is generally accepted in more and more societies around the world. The motivation for marriage might be weaker. Additionally, many societies used to expect young people to get married, and both pressure them to do so and facilitate them doing so by providing help finding mates and large financial gifts to the couple. This is no longer the case: there is not as strong an expectation, far less pressure, and exceedingly little facilitation.These explanations all matter. But imagine a world where they were all just as true as they are now: women were seeing a glamorous single life, men had porny brains, nonmarital sex was licit, societies didn’t support marriage… but also young men’s incomes hadn’t stagnated or fallen, but instead had risen as fast as young women’s, and so young men greatly out-earned young women.

Do you seriously think, in that scenario, that marriage rates would be as low as they are? That young men would not be leveraging their income into locking in desirable young women earlier in life? That young women would be talking about how lame, uninteresting, and undesirable young men are? No! Of course not! If young men were economically prospering, these cultural trends might exist, but their effects would not be the same.

I’m not saying there’d be no marriage decline if men’s incomes were doing well— but there’d be far less of one.

2. Marriage Subsidies Work

Let’s assume I’ve convinced you that economic motivations are a huge part of why people marry and how they select whom they will marry.

Contrast that with children: people don’t have kids for the money, at least not anymore. Peoples’ reasons for childbearing are more complicated and less directly related to money.

This should make us think that whereas subsidies for childbearing will require a lot of money to get a few babies, subsidies for marriage should require rather less money to get more marriage.

And this is, in fact, exactly what we find. Academic study of pro-natal incentives suggests that they do boost births, but the effects are very modest in scale.