In the last few weeks, lawyers and advocates have done the heroic and enormously valuable work of filing—and winning—many important lawsuits to stall many of the Trump/Musk blitzkrieg’s most egregious assaults. However, it’s dangerous to look at these cases as anything more than a holding action. They can stall or even stop some of the worst facts on the ground from taking root, but they cannot save us. To understand how we could save ourselves, we first have to understand exactly what we’re up against.

It’s very possible that once some of these legal cases reach the Supreme Court, the Trump Administration might openly defy rulings that attempt to limit it. Many argue that because of this possibility, we are on the precipice of a “constitutional crisis.”

They are wrong.

We are not on the precipice of a constitutional crisis; we are already deep into one, created by a nearly two-decade-long constitutional coup by the Roberts Court, which paved the way for the re-election of Donald Trump. That judicial overreach was not on behalf of “conservative principles,” but on behalf of right-wing funders that packed the courts to accomplish the Federalist Society’s revanchist agenda by judicial fiat,1 an agenda whose enactment through democratic processes was unimaginable.2

The Roberts Court IS the constitutional crisis. This is true in the most proximate sense because the Roberts Court shielded Trump from prosecution and accountability through unprecedented interventions in Trump v. US (the immunity decision) and Trump v. Anderson (Colorado ballot).3 Even before then, without the Roberts Court’s Citizen United decision legalizing unlimited spending by billionaires, Elon Musk’s central role now—both in funding a significant chunk of Trump’s campaign and in dictating the shutting down of core federal programs—would be unimaginable. And, as Jack Goldsmith argues, Trump v. US also opened the door to a “maximalist theory of executive power.”4

If we pull the camera back, we can see how the Roberts Court set the crisis in motion by changing the most fundamental ground rules of democratic elections through decisions like Citizens United, Shelby and Rucho. And finally, by making it clear through their rulings how easy it is to replace the rule of law with the rule of men, the Roberts Court has invited Trump to see himself as one of those men.

The bipartisan acceptance of judicial supremacy enabled the coup. By judicial supremacy, I mean the notion that in every instance the Supreme Court, not the American people and their elected leaders, has the final word on constitutional meaning. (More below.) Or, as John Roberts said on C-SPAN in 2009:

The most important thing for the public to understand is that we’re not a political branch of government. They do not elect us. If they do not like what we are doing, it is more or less just too bad.

As a result, we continuously repeat the category error that got us here by seeing the executive defying the Supreme Court, but not the Supreme Court defying popular understandings of Constitutional principles, as a constitutional crisis. (Both are.)

Should Trump ignore a court finding that he exceeded his authority, we will say that he precipitated a constitutional crisis—but should the Roberts Court reverse a lower court ruling to declare that Trump actually had that authority as executive all along, the media will say the Supreme Court averted a constitutional crisis. In other words, we act as if America is better served by capitulation than confrontation.

Judicial Supremacy vs. Popular Constitutionalism

The Founders did not intend for the Supreme Court to have the final say on constitutional meaning; instead, they expected constitutional interpretation to be an ongoing democratic process, shaped by legislatures, presidents, and the people themselves—a popular constitutionalism.5 And, indeed, the antebellum period was characterized by popular debate of constitutional meaning.6

And, in the aftermath of the Dred Scott decision, President Lincoln said in his first inaugural address:

If the policy of the Government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by the decisions of the Supreme Court... the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.

In 1935, as the Supreme Court was blocking key New Deal programs amid the economic devastation of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt echoed Lincoln, affirming that the Constitution was not a legal straitjacket but a living framework for self-governance—something that belonged to the people, not to a priesthood of legal experts. He said:

The Constitution of the United States was a layman's document, not a lawyer's contract. That cannot be stressed too often. Madison, most responsible for it, was not a lawyer; nor was Washington or Franklin, whose sense of the give-and-take of life had kept the Convention together.

This great layman's document was a charter of general principles, completely different from the "whereases" and the "parties of the first part" and the fine print which lawyers put into leases and insurance policies and installment agreements.

Until relatively recently, constitutional meaning was contested in the public sphere. Social movements and politicians continuously staked their claims in constitutional principles, as opposed to textual exegesis. Abolitionists refused to accept enslavement as settled law, the labor movement fought for constitutional recognition of workers’ rights, and the civil rights movement challenged the Court’s precedents, pushing constitutional meaning forward through direct action.

It is only towards the end of the 20th Century that judicial supremacy—the belief that only the Supreme Court has the power to define constitutional meaning—became dominant, largely as a result of liberal legal elites who valorized the Warren Court.7 Since then, corporate interests and conservative political movements have exploited this to advance their ultimate goal of undoing the democratically achieved gains of the New Deal and civil rights movements—in short, to repeal and replace the 20th century.

Progressive “institutionalists” enabled the judicial coup and continue to keep us from seeing what should be obvious. Unfortunately, progressive legal movements and scholars, despite their putative values, helped entrench judicial supremacy by situating particular civil rights and personal liberty gains as depending exclusively on the very system that has been turned against the realization of those values.8 Instead of challenging the Roberts Court’s authority to dictate constitutional meaning, they reinforce it by treating court rulings as the decisive arena for social progress. Their reliance on litigation, rather than political mobilization, ultimately constrains constitutional progress within a system where a simple 5-4 Roberts majority could overturn decades of democratic gains overnight, especially in a contest against an executive with little regard for the law.9

Even withering critics of originalism usually begin by acknowledging the premise that constitutional interpretation is a technocratic problem rather than a democratic challenge. But constitutions are first and foremost the contract between the governed and the government, which provides the former rights and the latter legitimacy. As such, the fundamental provisions of a constitution must be continuously legible to the governed. The moment the Roberts Court began to make a hash of that should have been the “break glass” moment for the progressive legal community.

Worse, too many progressive institutionalists were (and continue to be) as energetic in decrying those who attack the Court’s corrupt judicial overreach10 as they are attacking the substance of the bad rulings, insisting that we have more to lose by criticizing SCOTUS than by acknowledging that the Court has been captured. In doing so, progressive institutionalists have forestalled mobilizing the necessary popular opposition. Even more foolishly, some progressive litigators believe that public criticism of the Court will hurt their chances of winning their cases.

The Rule-of-Law vs. the Rule-by-Fiat

To a first approximation, the most immediate crisis can be seen in the framework of judicial supremacy as pitting what I will call the Rule-of-Law vs. the Rule-by-Fiat systems. By “Rule-of-Law,” I mean something more specific than the typical understanding of “rule of law”—essentially, the good-faith practice of adhering to democratic legal principles.

The Federalist Society Rule-by-Fiat

Rule-by-Fiat, consisting of judges and justices installed by and loyal to the Federalist Society, represents outcome-driven jurisprudence that disingenuously changes the law to accomplish outcomes that favor specific interests. Once cases reach the Rule-by-Fiat system, outcomes follow power relations rather than legal principles.11

We can see that clearly in the cases most directly relevant to power relations—those that alter the political system, something the Warren Court never did with less than seven bipartisan votes, and when it did, it was to make the system more democratic. The Roberts Court, in contrast, routinely decided on strictly partisan lines to give its Federalist Society backers more power in the political system.12

Today we are caught in a collision between those two systems. The “Rule-of-Law” judicial system consists of judges who weren't vetted through the Federalist Society network (including some appointed by Trump early in his first term) who continue applying constitutional principles and legal precedent.

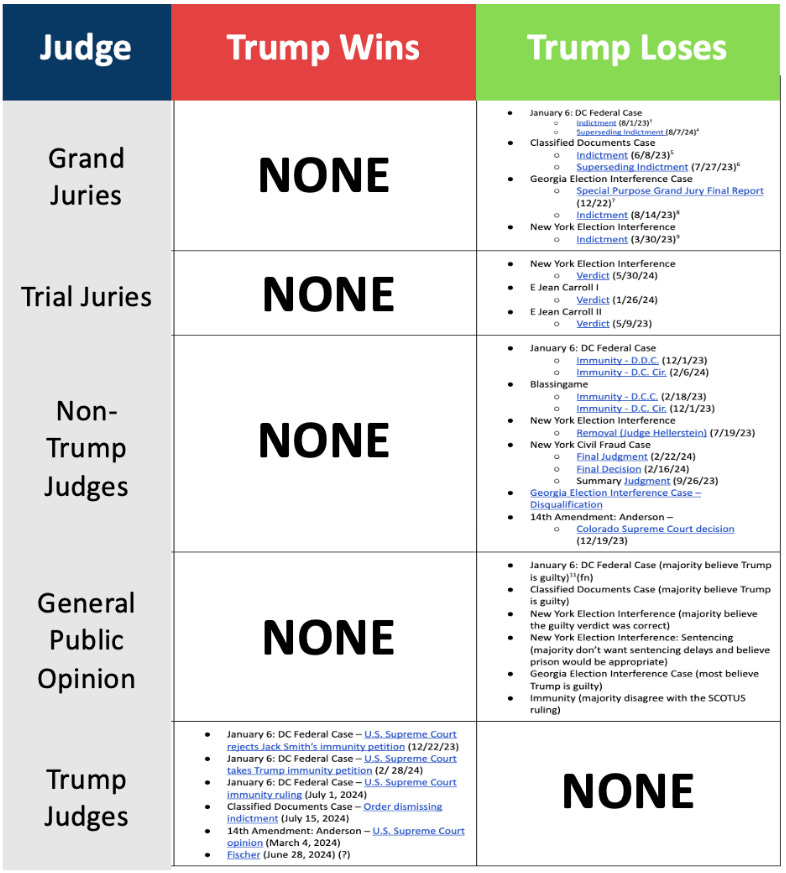

In 2023 and 2024, in the Rule-of-Law judiciary, every time Trump’s crimes were brought to a grand jury, he was indicted; every time Trump faced a trial jury, he was convicted; and every time his cases came before judges he did not name, he lost. But every time he appealed those defeats to the Rule-by-Fiat judicial system, the Roberts Court or judges he named not only overruled those setbacks but used them as pretexts to go further than even he had argued in some cases.13

At this point, some may object, pointing to how comprehensively SCOTUS rejected Trump’s claims in 2020. As I explained here at length, in 2020 the business community, including the MAGA-backing Koch network, favored respecting the results of the election. But by 2023, there had been a major shift in allegiance in the corporate community and among key Federalist Society backers.

Corrupting “the Rule of Law”

Rule-by-Fiat has corrupted the unhyphenated, popularly understood concept of “rule of law,” making it a slippery and dangerous notion. Devotion to the unhyphenated “rule of law” presumes the law itself was democratically legitimate. However, when those laws, or the Constitution itself, have been remade by judicial fiat, the uncritical acceptance of the “rule of law” makes us complicit in our own demise.

It’s important to understand that while the Federalist Society has a general consensus on the end game of what the Constitution should mean, there is an important division between those who believe in the most shameless and roughshod implementation of Rule-by-Fiat, and those who favor a more gradual approach because they staunchly believe in adhering to the rule of law along the way.

I’ll give a couple of examples to make the distinction clearer. Federal judges like Aileen Cannon and Matthew Kacsmaryk are firmly in the “shameless” camp. Brad Raffensperger, by contrast, would not break the law to find Trump 11,780 votes—but had before the election actively worked to make it more difficult to vote in Atlanta, and after the election actively supported SB 202 to make it even more difficult for Georgians to vote and less difficult for state election administrators like himself to use their discretion after the election. Or, most recently, the revolt against the Adams deal by SDNY attorneys included those who had clerked for Scalia and Roberts—people who courageously upheld the “rule of law” when doing otherwise was too obvious a violation, but who had eagerly participated in Rule-by-Fiat in more legitimate-seeming contexts. In other words, the Federalist Society gradualists believe that justice must be blind in executing the law, but they have no problems with using the judiciary to make new law or rewrite the Constitution from the bench.

How to Restore Popular Constitutionalism

When I raise this idea of public or democratic constitutionalism, I’m inevitably greeted with the blank stares of learned helplessness that judicial supremacy has wrought in us. That calls to mind the useful observation of uncertain origin that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of neoliberalism.” Similarly, even though public or democratic constitutionalism characterized most of the nation’s history, the recent triumph of judicial supremacy makes it difficult to imagine what popular constitutionalism might actually look like.

So what might popular constitutionalism have looked like in 2022 when the Dobbs decision was delivered?

Let’s start with elected Democrats, since at that time they had a trifecta. They could have (1) done a filibuster carve out to codify Roe; (2) investigated and held high visibility hearings as to the role of Leonard Leo, the Federalist Society, and Opus Dei; and (3) held high visibility hearings on the trends in maternal and infant mortality in the states with increasingly aggressive abortion bans. Of course, there was really no excuse to wait to do any of those steps until Dobbs. Moreover, Senate Democrats could have taken all of those steps in the last two years, even though the loss of their House majority would have prevented legislative enactments.

In order to help recover popular constitutionalism, here are several things we must all do, and demand our allies follow suit. It boils down to insisting that we simply speak truth to each other.

1. Don’t say “the Supreme Court”—it’s the Roberts Court.

When we say “the Supreme Court did X,” even if we loudly object to X on the “merits,” we give X unwarranted legitimacy by naming the hijacked institution rather than the hijackers. When progressive institutionalists scold us for undermining the credibility of the Court, they do not realize that attributing its worst opinions to the institution rather than its hijackers degrades public trust in the institution even more. This is why, at Weekend Reading, I usually refer to “the Roberts Court” or “the (MAGA/Federalist Society/Republican-appointed) justices.”

Purely in terms of linguistics, accurately naming the problem is a prerequisite to problem solving and mobilization. Consider the effect it had when the South attributed the Brown decision to the “Warren Court” to avoid conferring it with the legitimacy due the Supreme Court. Reflexive institutionalists often use Brown as a “what’s good for the goose is good for the gander” rejoinder to those who decry the Roberts Court disregarding precedent in cases like Dobbs. In fact, that reflex reveals the institutionalists’ utter shallowness, because if Brown is a goose, the Roberts Court decisions are not gander.

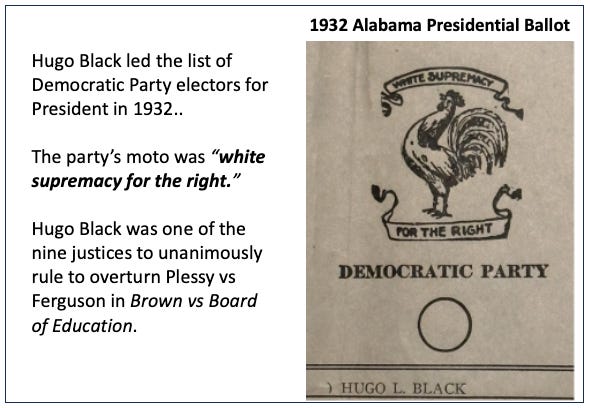

Brown should be considered an institutional opinion, as it was reached unanimously by justices—including former segregationists—who had been nominated by Democratic and Republican presidents and had been confirmed overwhelmingly by bipartisan majorities.14

The opposite is true of the Roberts Court. It reserves its most nakedly partisan and divisive rulings to overturn some of America’s most important precedents. None of these decisions have been bipartisan, let alone unanimous; all of them reflect the prior views of the justices in the majority; and, most importantly, all of the decisions accomplished the agenda of the Federalist Society coalition which engineered those justices’ nominations and confirmations. The NAACP did not pack the courts to produce Brown, but the billionaire backers of the Federalist Society did pack the court to get their wins.15

What’s more, these decisions are coming from the most minority-rule Court in American history, which also has the least public confidence of any Supreme Court we have such polling data for. It is legitimate and essential to understand that the Roberts Court is unlike any other, even ones responsible for some of the worst decisions in American history16:

Unrepresentative.

Five of the six Roberts majority justices were appointed by presidents who did not win the popular vote.

Five of the six are the only five of the 81 to serve since the Civil War who were confirmed by senators who represented less than half of the US population. Before the confirmation of Clarence Thomas, it was extremely rare for a justice to be confirmed by senators representing less than 90 percent of the US population.

Engineered for the mission. All six are part of the billionaire-sponsored Federalist Society project to overturn the democratic progress of the 20th Century by judicial fiat. (See To the Supreme Court, the 20th Century Was Wrongly Decided)

Uncompromisingly outcome-oriented. (See Politicians in Robes: The Roberts Court - Dictators Since Day One)

And, remember that every Roberts Court opinion will depend on the three justices Trump himself named—one whose seat was stolen when McConnell refused to allow Obama to fill Scalia’s vacancy starting nine months before the 2016 election, and the other who McConnell rammed through even as voting was already underway in the 2020 election. Three of the justices on the Court—Kavanaugh, Barrett, and Roberts himself—rose through the judicial ranks after they worked on Bush’s legal team in Bush v. Gore, the country’s original judicial coup.

2. Develop and deploy a vocabulary that distinguishes what is momentarily legal from what is eternally legitimate.

At crucial moments in American history, the difference between what is legal and what is legitimate has been obvious, and has been a necessary precondition to the most important advances toward a more democratic society. In his Letter from a Birmingham Jail, Martin Luther King wrote:

We should never forget that everything Adolf Hitler did in Germany was ‘legal’ and everything the Hungarian freedom fighters did in Hungary was ‘illegal.’

Unlike King, who was asking us to see an America that not yet was as the legitimate instance of the nation, the Roberts Court and Trump erase the democratic accomplishments we’ve made to get closer to King’s vision. Therefore we must battle for honest vocabulary now, lest we ignore what dissidents in totalitarian regimes well understand—that “The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting.”17

3. Don’t praise Roberts for doing “the right thing.”

If we expect the Roberts Court to act as a rubber stamp for everything Trump wants, we misunderstand the incentives driving its decisions. Shielding Trump before the election was a means to an end: ensuring that a Democratic president could not interrupt or reverse the Federalist Society’s judicial coup. Now that this is done, the Roberts Court will almost certainly rebuke Trump on several consequential matters when he clashes with certain factional interests. There have been and will continue to be conflicts within the Republican Coalition, which, broadly speaking, consists of several factions.18

Therefore, we must understand that in addition to relentlessly securing the outcomes around which that coalition is aligned, the Roberts Court acts as the de facto coalition manager when coalition interests are not aligned. Such misalignment most often occurs when Christian nationalist and other radical right wing demands conflict with corporate interests—and the latter usually wins those battles. It is also important to understand that when the short term electoral interests of the Republican Party conflict with the larger interests of the coalition, the Roberts Court sides with the latter over the former; they are not partisan hacks, they are interest group hacks.

This insight helps us understand why ascribing the actions of the Roberts Court to either partisan or ideological ends misses the deeper pattern. Instead, the Roberts Court now manages a complex balancing act between competing power centers in our interregnum—most notably between transnational capital and nationalist reaction. Thus, in 2020, when corporate interests were united behind respecting the results of the election, the Roberts Court rejected Trump. (I provided more examples of this in Politicians in Robes: Part III: The “Exceptions” That Prove the Rule.)

Trump will use the Roberts Court to resolve conflicts between the MAGA and business factions within his coalition in order for him to continuously be the “good cop” to the theocratic/right wing base, taking the maximalist positions, while Roberts is the “bad cop” defending the interests of the business side of the coalition when that is necessary. We can almost certainly expect a “bad cop” ruling to stop Trump from ending birthright citizenship, for instance, since his executive order went far beyond previous expectations.

By definition, any time an appeals court Rule-of-Law decision is affirmed, it will be a bipartisan outcome—two Federalist Society justices will have joined Justices Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson.19 We can attribute those affirmations of Rule-of-Law decisions to “the Supreme Court” because in those cases, it is fulfilling its constitutional function.

However, we must be wary because, as Adam Liptak noted in 2013:

Chief Justice Roberts has proved adept at persuading the court’s more liberal justices to join compromise opinions, allowing him to cite their concessions years later as the basis for closely divided and deeply polarizing conservative victories.

Most recently, this happened in Moore v. Harper, which was celebrated by pro-democracy advocates because it rejected the outrageous “independent state legislature” theory. But the hidden democracy-eroding outcome was to establish that any decision that may be made by a state supreme court with respect to the presidential elections is now presumed to be appealable to SCOTUS.20

In short, as Brennan Center President Michael Waldman recently said, “Liberals have to fall out of love with the Supreme Court.

4. Be wary of the Roberts Court for its faux institutionalism.

Roberts also attempts to manage the methods and pace by which his court reaches its predetermined outcomes, believing that incremental approaches and rejection of sloppy lawyering sustains the credibility of the court. That approach is now clearly in tension with the impatience of Trump, Musk, and their minions. So we mustn't confuse Roberts’ willingness to slap them down when they don’t dot their i’s or cross their t’s for an unwillingness to go along when they do. That was the pattern in the first Trump Administration with respect to the travel ban, for example.21

5. Connect Roberts Court cases to their consequences.

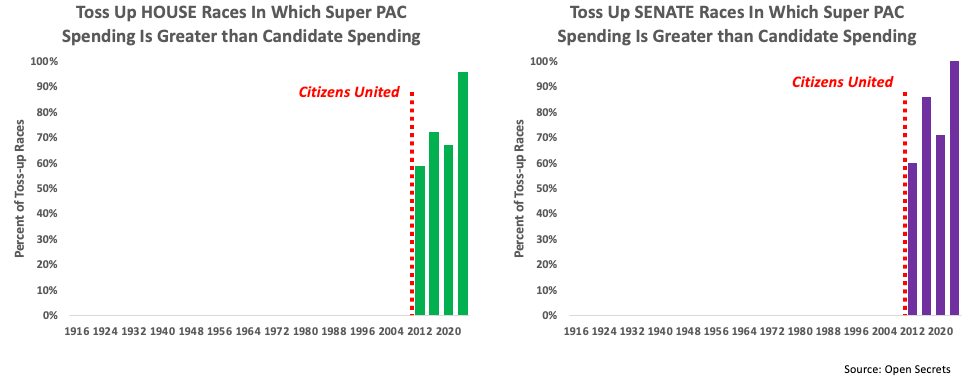

None of the reporting about Musk—even about the $290 million he spent to make himself co-president—has even mentioned that until the Roberts Court 5-4 decision in Citizens United, that spending would have been illegal. Without Citizens United, there is no DOGE.

Consider how meaningful that long-forgotten context is:

Citizens United was a response to the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA), which was enacted when Republicans controlled both the House and Senate, and was signed by George W. Bush. It received 60 votes in the Senate and 240 votes in the House.

The justices expanded the question presented to enable themselves to deliver a more sweeping opinion.

That opinion was deferred from the OT 2008 Docket to the OT 2009 Docket because after Justice Souter wrote a blistering draft dissent, Roberts ordered the case to be reheard in the next term, after Souter had retired.22

The five partisan justices represented a smaller majority of the Supreme Court’s nine votes than the bipartisan Congressional majorities that enacted BCRA. And so, a Supreme Court majority engineered by billionaires legalized unlimited political spending by billionaires. And, just four presidential cycles since such outside spending was illegal, outside interests spent more in every toss-up House and Senate race—the races that decided control of each chamber—than the candidates in those races did themselves.

6. Name names, not legal precedents.

How is it that money matters more in American politics than in any other major putative democracy, yet the narration of our lives and crises proceeds exclusively as conflicts between institutions (Congress vs the Executive!), between political parties (Democrats vs Republicans!), or between ideologies (Liberals vs Conservatives!)? These frames completely erase the intentions and influence of those who contribute most of the tens of billions of dollars spent electing members of Congress and the President, who support the careers and nominations of Supreme Court Justices, who spend $15 billion lobbying Congress, and who spend untold billions endowing law schools and funding think tanks.

As John Dewey noted a century ago, "politics is the shadow cast on society by big business." With its Federalist Society origins, that shadow is being cast on the judiciary as well. Yet we easily hide that behind the veil of abstraction. For example, rather than analyzing Court rulings through conventional legal frameworks, we must examine them through the lens of specific plutocratic and theocratic interests. The contradictions disappear when viewed this way: one ruling that expands executive immunity and another ruling that limits regulatory agencies make perfect sense when the axis runs not from government power to individual rights, but from the Koch network’s interests to democratic accountability.

And, again, the mostly billionaire- or corporate-owned media—including the experts we trust—are willing participants in this obfuscation. They continuously deflect attention from the intended beneficiaries and likely consequences of a Roberts Court decision by characterizing those decisions in terms of ideology (“conservative”) or legal approach (“originalism”). An example of that was the coverage of Loper Bright, the opinion that overturned the Chevron doctrine. Even strong critics of Loper Bright framed it as a power struggle over whether judges or agencies should be the ones to interpret Congress' efforts to protect workers, consumers, and the environment, when it was really about whether workers, consumers, and the environment will be protected from corporate predations at all. It wasn’t a “judicial power grab,” but a corporate power grab on behalf of the Federalist Society corporate interests.

Inevitably, institutionalists, even those who are harshly critical of Roberts Court decisions, explain those outcomes exclusively in terms of the law itself, without reference to the interests of those who will gain or lose.23 If you are following SCOTUS related Substacks, blogs, and podcasts, consider (1) how much more you’ve heard about Humphrey’s Executor in discussions of the “Unitary Executive Theory” than you have heard about who will gain and lose if the Roberts Court goes along with Trump; (2) that in its origins and intentions, the unitary executive theory is just as intellectually empty and transparently pretextual as originalism; and most importantly (3) how you never hear the popular constitutionalism argument for independent agencies—the extent to which independent agencies, both in intent and in effect, have played an essential safeguard against tyrannical presidential power.

Although beyond this Substack, it is worth noting that within the community of legal scholars, a more expansive approach is beginning to take shape. For example, the Law and Political Economy (LPE) Project’s work is “rooted in the insight that politics and the economy cannot be separated and that both are constructed in essential respects by law” and aims to develop “ideas and proposals to democratize our political economy.”

We Have Ceased to Be Our Own Rulers

The need to unmask the corruption of the judicial process by the Roberts Court and the Federalist Society could not be more urgent. Consider that in the next four years, at a minimum, Alito and Thomas could step aside for much younger justices, sealing at least a 5-4 Federalist Society majority for decades. And in the nearer term, consider the impact of Trump’s packing the federal judiciary with more Kazmaryks and Cannons.

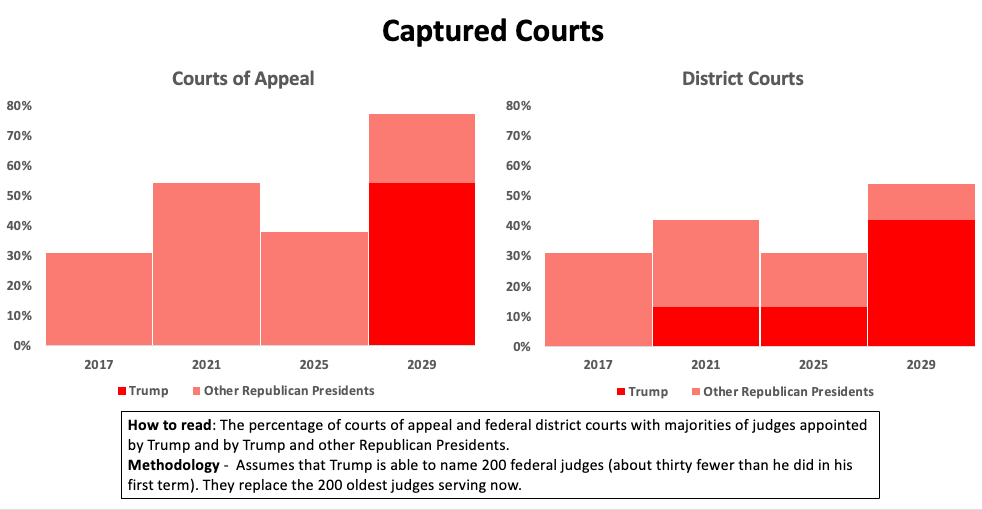

In this chart, I made the simple assumption that Trump will be able to name 200 federal judges, about thirty fewer than he did in his first term. Then I assumed those would replace the 200 oldest judges serving now. Here are the results:

As long as we continue to cede unwarranted legitimacy to John Roberts and the other five politicians in robes by naming their shredding of the constitutional order the “rulings” of the “Supreme Court,” we will continue to dig democracy’s grave. And, as long as we defer to our well-meaning legal allies who insist that constitutional interpretation is a technocratic calling, we reinforce the suffocating judicial supremacy that keeps us helplessly subservient to a “rule of law” in which billionaire-installed justices change the law continuously to meet their needs.

Weekend Reading is edited by Emily Crockett, with research assistance by Andrea Evans and Thomas Mande.

For more on the Federalist Society project to remake the law to suit its sponsors see: Whitehouse, Senator Sheldon, Captured: The Corporate Infiltration of American Democracy; Whitehouse, Senator Sheldon, Mueller, Jennifer, The Scheme: How the Right Wing Used Dark Money to Capture the Supreme Court; Daley, David, Antidemocratic: Inside the Far Right's 50-Year Plot to Control American Elections; Millhiser, Ian, The Agenda: How a Republican Supreme Court is Reshaping America; Teles, Steven M., The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The Battle for Control of the Law; Hollis-Brusky, Amanda, Ideas with Consequences: The Federalist Society and the Conservative Counterrevolution; Cohen, Adam, Supreme Inequality: The Supreme Court's Fifty-Year Battle for a More Unjust America; Avery, Michael, McLaughlin, Danielle, The Federalist Society: How Conservatives Took the Law Back from Liberals; Hollis-Brusky, Amanda, Wilson, Joshua C., Separate but Faithful: The Christian Right's Radical Struggle to Transform Law & Legal Culture; Baum, Lawrence; Devins, Neal, The Company They Keep: How Partisan Divisions Came to the Supreme Court

In Change No One Could Have Believed, I inventory the massive changes—for the worse—the Roberts Court has accomplished since then, without a vote ever having been taken in Congress, including enabling billionaires to swamp elections with unlimited spending, which had previously been illegal; all but repealing the Voting Rights Act; giving a free hand to politicians to draw their own districts; revoking women’s constitutional right to an abortion; gutting anti-corruption laws while fortifying the rights of white-collar criminals; and making it all but impossible for consumers and workers to bring corporations to court or to file class actions.

The Trump v. Anderson ballot case baselessly neutered Section 3 of the 14th Amendment that precludes oath-breaking insurrectionists from holding office, and the immunity decision was widely panned as blatantly contrary to the language and structure of the Constitution. In addition, while the Court leapt into action to keep Trump on the ballot in Trump v. Anderson, it fabricated an excessively long delay in issuing the immunity case—itself an act of interference.

Jack Goldsmith notes (quoting Adrian Vermeule, the founder of “common-good constitutionalism,” a legal “theory” gaining favor as the successor of originalism), the most immediately damaging aspect of the immunity decision wasn’t immunity, but that taken to its logical end, the decision “constitutes a ‘maximalist theory of executive power’ that exceeds even ‘the standard version of unitary-executive theory.’”

For a good introduction to popular constitutionalism, see, for example, Kramer, Larry D., The People Themselves: Popular Constitutionalism and Judicial Review. For an extensive history of the role of popular constitutionalism, see Bruce Ackerman’s We the People: Foundations and We the People: Transformations.

See, for example, The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution: Reconstructing the Economic Foundations of American Democracy by Joseph Fishkin and William E. Forbath, and The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Anti-Slavery Constitution by James Oakes.

David Fontana writes in The Rise and Fall of Comparative Constitutional Law in the Postwar Era how this more technocratic, case law based approach was effectuated through legal education and scholarship:

In the first few decades after World War II, comparative constitutional law rose to a prominent position in American law schools, only to disappear in many ways in the years after the Warren Court in part because of the Court’s decisions. During the years after World War II, Justices of the Supreme Court (from William Douglas to Felix Frankfurter to Earl Warren) and deans of major American law schools (like Harvard Law School Dean and later Nixon Solicitor General Erwin Griswold) traveled the country and the world encouraging everyone to examine the constitutional law of other countries. Law reviews featured many articles about comparative constitutional law, sometimes nearly as many as about decisions of the United States Supreme Court. With time, though, the attention devoted to the Warren Court and the Court’s decisions led to a substantial disappearance of comparative constitutional law from the American legal world.

See also Kim Lane Scheppele’s Aspirational and aversive constitutionalism: The case for studying cross-constitutional influence through negative models.

Indeed, especially over time, liberals came to believe that racial justice alone motivated Brown. In fact, national security considerations were crucial, and there’s a strong argument that Brown attenuated the possibilities of the civil rights movement. In Cold War Civil Rights, Mary Dudziak writes:

… the Cold War would frame and thereby limit the nation’s civil rights commitment. The primacy of anticommunism in postwar American politics and culture left a very narrow space for criticism of the status quo. By silencing certain voices and by promoting a particular vision of racial justice, the Cold War led to a narrowing of acceptable civil rights discourse … to the extent that the nation’s commitment to social justice was motivated by a need to respond to foreign critics, civil rights reforms that made the nation look good might be sufficient … the federal government engaged in a sustained effort to tell a particular story about race and American democracy: a story of progress, a story of the triumph of good over evil, a story of U.S. moral superiority. The lesson of this story was always that American democracy was a form of government that made the achievement of social justice possible, and that democratic change, however slow and gradual, was superior to dictatorial imposition. The story of race in America, used to compare democracy and communism, became an important Cold War narrative.

Thus, the Cold War-era civil rights movement was constrained by political realities that excluded broader discussions of economic justice. Before Brown v. Board of Education, legal challenges to Plessy v. Ferguson focused heavily on economic rights, as noted by then-Solicitor General Robert Jackson in 1938. Throughout the 1940s, activists prioritized fair wages, union access, and workplace equality over school desegregation.

Risa Goluboff’s The Lost Promise of Civil Rights highlights this overlooked legal history. From an establishment perspective, school desegregation was the least disruptive solution, strategically responding to Cold War pressures and Soviet propaganda. However, Brown v. Board was delayed by Brown II, making it the only Supreme Court ruling that did not take immediate effect, as Sherrilyn Ifill has argued.

See, for example, Barton Gellman in the Washington Post last year: How to harden our defenses against an authoritarian president: A commander in chief with little concern for legal limits holds a big advantage over any lawful effort to restrain him.

By “corrupt” I don’t mean the actions of individual justices in particular cases, but the corruption of the democratic process itself.

To cite a few examples so egregious that no other conclusion is possible other than that the outcomes were predetermined. In Captured, Senator Sheldon Whitehouse writes, (and then develops in great detail):

Unleashing the corporate power Citizens United set loose in our elections required the conservative justices to go through some pretty remarkable contortions: reversing previous decisions by the Court that had said the opposite, making up facts that are demonstrably flat-out wrong, creating a make-believe world of “independence” and “transparency” in election spending, and maneuvering their own judicial procedures to prevent a factual record that would belie those facts they were making up. Each of the contortions was unusual, objectionable, wrong, or all of the above. (Whitehouse, Senator Sheldon. Captured: The Corporate Infiltration of American Democracy (pp. 104-105). Kindle Edition.

Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson directly rebuked the Roberts majority in Trump v Anderson for settling "novel constitutional questions to insulate this court and petitioner [Trump] from future controversy."

After the Shelby County v Holder case, respected conservative judge Richard Posner wrote:

This is a principle of constitutional law (equal sovereignty) of which I had never heard—for the excellent reason that, as Eric points out and I will elaborate upon briefly, there is no such principle.

Michael Waldman provides a compelling history of the Roberts Court’s rule by fiat in The Supermajority: How the Supreme Court Divided America. Among the compelling critiques of originalism, their pretext for legislating from the bench, include: Chemerinsky, Erwin, Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism, Dennie, Madiba K., The Originalism Trap: How Extremists Stole the Constitution and How We the People Can Take It Back and Gienapp, Jonathan, Against Constitutional Originalism: A Historical Critique. Also, Slate’s How Originalism Ate the Law.

Campaign Finance: Citizens United v. FEC, Arizona Free Enterprise Club’s PAC v. Bennett (struck down public financing), McCutcheon v. FEC

Voting Rights: Shelby County v. Holder, Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute (upheld voter roll purge)[With Barrett on the Court, Brnovich v. DNC 6-3]

Gerrymandering: Rucho v. Common Cause

Trump: Trump v. Anderson, Trump v. US

See “In Any Other Country.”

As well described in various accounts, Chief Justice Earl Warren worked strenuously to fashion a unanimous opinion in Brown, which included the assent of Justices Hugo Black (formerly a senator from Alabama) and Stanley Reed who initially said he “opposed abolishing segregation.” Likewise, Roe v. Wade (7-2) involved extensive and well-documented efforts at consensus-building, and justices appointed by both parties signed on to the majority opinion. (Simple Justice (Richard Kluger) p. 598)

See footnote 1 for resources about the Federalist Society.

The brazen disregard of good faith jurisprudence is more comprehensively detailed in Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s book Captured: The Corporate Infiltration of American Democracy (beginning on p. 93).

Kundera, Milan. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. Harper & Row, 1980

Broadly speaking, the factions are (1) the Koch aligned network, (2) “mainstream” Chamber of Commerce corporate, (3) Musk/tech, and (4) theocrats.

Those opposing Trump’s actions will have to be strategic about when they appeal lower court losses to the Roberts Court. While they may seek appeals on blatantly unconstitutional executive action, they will be reluctant to have such an activist Court adjudicate many important issues, and so many if not most of the cases appealed to the Roberts Court will be those that the Trump Administration lost in Rule-of-Law courts. Therefore, we might see very few true Rule-of-Law rulings on Trump/Musk cases from the Roberts Court.

Remember, that proposition was shockingly unprecedented when SCOTUS intervened in Bush v. Gore to stop the counting of ballots. If November had resulted in a narrow Trump loss, or if one or two states were too close to call, Moore v. Harper could have set the stage for the Roberts Court to intervene and throw the election to Trump.

In 2017, the first two versions of Trump’s travel ban (Executive Orders 13769 and 13780) were blocked by lower courts, but in Trump v. Hawaii (2018), the third version of the travel ban was upheld in a 5-4 Roberts Court decision. In other instances, SCOTUS let lower court rulings stand until the Trump Administration reformulated its actions or arguments. For more on this dynamic, see Biskupic, Joan, Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic Consequences and The Chief: The Life and Turbulent Times of Chief Justice John Roberts; and Greenhouse, Linda, Justice on the Brink: A Requiem for the Supreme Court.

Jeffrey Toobin reported:

Souter wrote a dissent that aired some of the Court’s dirty laundry. By definition, dissents challenge the legal conclusions of the majority, but Souter accused the Chief Justice of violating the Court’s own procedures to engineer the result he wanted.

… Souter’s attack—an extraordinary, bridge-burning farewell to the Court—could damage the Court’s credibility. So the Chief came up with a strategically ingenious maneuver. He would agree to withdraw Kennedy’s draft majority opinion and put Citizens United down for reargument, in the fall.

The exceptions are abortion and other gender related issues where (with justification) progressive judicial supremacists call out the misogyny and corruption of the justices, most usually Alito and Thomas.

Some excellent reading, reminders of how we actually fit in the equation of a democracy.

Question: I’ve been reviewing the Constitution and wonder about trumps and Vance’s recent actions of aiding the enemy, with a clear intention to destroy our democracy/country.

Why isn’t Congress taking this up? It’s clearly treason, IMHO

Excellent piece and excellent principles! Allow me to provide an example that supports and illustrates some of your points.

The primary point of Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803) (Marshall, C.J.) was that even if all three branches conspired to violate our Constitution, they still could not override our Constitution. It is well settled (including in Marbury v. Madison) that our Constitution did not vest in any federal judge any power to lie about or knowingly violate our Constitution. I could barely believe my eyes when I saw the SCOTUS majority in Dobbs lie about the Ninth Amendment and then knowingly violate the Ninth and Tenth Amendments.

The Tenth Amendment obviously emphasized that federal judges could not exercise any "powers" that were "not delegated to the United States by the Constitution." The Ninth Amendment obviously emphasized that a particular power was not delegated to federal courts.

The majority in Dobbs (twice) knowingly and absurdly misrepresented that the Ninth Amendment stated a mere "reservation of rights to the people." The Ninth Amendment clearly was not merely (or even primarily) a "reservation of rights." The Ninth Amendment clearly is what judges commonly call "a rule of construction." It expressly and emphatically commanded how "the Constitution" absolutely "shall not be construed."

The Ninth Amendment expressly and emphatically commanded judges not to do exactly what the Dobbs majority did, i.e., not construe our Constitution "to deny or [even] disparage" any right "retained by the people" on the grounds that a right was not expressly included in any "enumeration in the Constitution." That command was clearly directed especially at judges whose duty is to construe the law (say what the law is).

After the Dobbs majority lied about the meaning of the Ninth Amendment, they knowingly violated it. They deceitfully focused our attention on the obviously irrelevant fact that “[t]he Constitution makes no express reference to a right to obtain an abortion." Then, they lied again. They knowingly misrepresented the consequence (dictated by our Constitution) of the foregoing irrelevant fact: "therefore those who claim that [our Constitution] protects [any] right [at issue] must show that the right is somehow implicit in the constitutional text.”

The Dobbs majority abused the foregoing lies about the law and their violation of our Constitution to pretend to justify shifting the crucial burden of proof--from the government (when it infringed on rights) onto citizens (asserting rights). The misrepresentation of law and violation of law by the Dobbs majority was clearly barred by the plain text and plain meaning of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments. It's almost unbelievable that those judges dared to do what they did in writing.

The Dobbs majority did not--and cannot--prove that their conduct and contentions did not violate our Constitution. Amendment I especially clearly barred judges from abusing their positions and powers for the "establishment" of their own "religion" or imposing their religious viewpoints on other persons (as they did in Dobbs). Amendment XIII clearly barred judges from abusing their positions and powers to facilitate "involuntary servitude" by other persons. Compelling a woman (or a couple) to involuntarily support a fetus (for some 9 months) and then a child (for some 18 years) necessarily is involuntary servitude. Moreover, our Constitution also clearly does guarantee a woman's right to use deadly force (even against another actual person and even against a citizen) for self-defense or self-preservation. That was the emphatic point of a decision by the same SCOTUS majority separated by only one day from their Dobbs decision. See all the many references to defense (or defence) or preservation in the analysis of the meaning of Amendment II in N.Y. State Rifle & Pistol Ass’n v. Bruen, 597 U.S. 1 (2022) (and even far more so in District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008)).

Contrast what the Dobbs majority did with conduct that Congress made criminal.

Any judges “conspir[ing] to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” any person “in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to” them “by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of” their “having so exercised” any such “right or privilege” commit a crime. 18 U.S.C. 241.

Any judge acting “under color of any law” or “custom” to “willfully” deprive any person “of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by” any provision of the “Constitution” or federal “laws” commits a crime. 18 U.S.C. 242. No judicial action or custom is exempt, including so-called deference, comity, reciprocity, res judicata, presumptions or pretenses (e.g., that hearsay by judges is true or is evidence it is true). In Section 242, the “qualification” regarding “alienage, color and race” is inapplicable “to deprivations of any rights or privileges.” United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299, 326 (1941).

“Even judges” clearly “can be punished criminally” under 18 U.S.C. 241 or 242 “for willful deprivations of constitutional rights.” Imbler v. Pachtman, 424 U.S. 409, 429 (1976). Accord Dennis v. Sparks, 449 U.S. 24, 28, n.5 (1980); Briscoe v. Lahue, 460 U.S. 325, 345, n.32 (1983); Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) (criminal prosecution of judge for abuse of official power).

That last decision (Virginia) is featured in a significant number of SCOTUS justices' opinions, esp. those of Justice Thomas, as well as in the D.C. Circuit decision and in DOJ briefing in Trump's immunity case.