This thing will fail

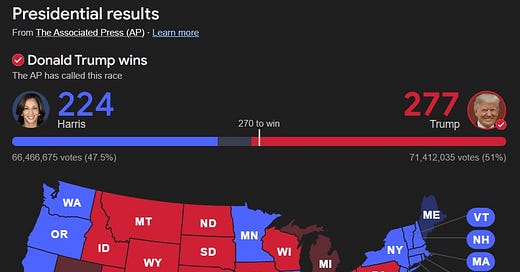

Trump will not restore the "strong gods" of community, family, and faith.

“Men don’t care what’s on TV. They only care what else is on TV.” — Jerry Seinfeld

N.S. Lyons is a popular essayist in the “national conservative” tradition. His Substack, The Upheaval, is recommended reading, even though I agree with less than half of what he writes. He is well-read and well-informed, he integrates information from across many domains, and he isn’t afraid to think deeply about the big questions of history in real time. Reading him will help you better understand the beliefs of the modern Right. On many questions, such as the threat of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, his message is one that people in the MAGA world desperately need to hear.

In a recent essay entitled “American Strong Gods”, Lyons identifies what in my opinion is a deep truth about our current historical moment. He writes of the end of the “Long Twentieth Century”, a period that was defined by liberalism (social, political, and economic), and anchored by rejection of Adolf Hitler:

I believe that what we’re seeing today truly is the end of an era, an epochal overturning of the world as we knew it, and that the full import and implications of this haven’t really struck us yet.

More specifically, I believe Donald Trump marks the overdue end of the Long Twentieth Century…

Our Long Twentieth Century had a late start, fully solidifying only in 1945, but in the 80 years since its spirit has dominated our civilization’s whole understanding of how the world is and should be…In the wake of the horrors inflicted by WWII, the leadership classes of America and Europe understandably made “never again” the core of their ideational universe. They collectively resolved that fascism, war, and genocide must never again be allowed to threaten humanity…

The anti-fascism of the twentieth century morphed into a great crusade…By making “never again” its ultimate priority, the ideology of the open society put a summum malum (greatest evil) at its core rather than any summum bonum (highest good). The singular figure of Hitler didn’t just lurk in the back of the 20th century mind; he dominated its subconscious, becoming a sort of secular Satan…This “second career of Adolf Hitler,” as Renaud Camus jokingly calls it, provided the parareligious raison d'etre for the open society consensus and the whole post-war liberal order: to prevent the resurrection of the undead Führer…

The Long Twentieth Century has been characterized by these three interlinked post-war projects: the progressive opening of societies through the deconstruction of norms and borders, the consolidation of the managerial state, and the hegemony of the liberal international order. The hope was that together they could form the foundation for a world that would finally achieve peace on earth and goodwill between all mankind.

Like all good essays, this overstates its case. The American-led liberalism of the postwar order was not a purely defensive project. The UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were not motivated by fear of Hitler’s return, but by a desire to expand the boundaries of human freedom and dignity beyond anything seen in the prewar period. Ronald Reagan didn’t need Hitler as a bogeyman to proselytize his vision of American freedoms as a universal ideal.

And yet there is an important sense in which Lyons is right. The spectacular horrors and the spectacular failure of Hitler’s regime provided a moral anchor that liberals could always use to argue for greater liberalism. Advocates of the Civil Rights Act and other liberalizing laws in the U.S. and Europe often used Nazi Germany as a rhetorical foil. Anticommunism provided the Right with an alternative Satan for a while, but it never quite had the same power, because America had been Stalin’s ally in World War 2; after the Soviet Union fell, anticommunism was quickly forgotten, but Hitler and the Nazis were not.

Lyons is right that the Trump Era marks the end of Hitler as the summum malum of Western culture — at least in the United States. Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson, the two most popular media figures on the American Right, have invited Darryl Cooper — a revisionist historian who downplays Nazi atrocities and views Winston Churchill as the true villain of World War 2 — to speak on their shows. Here is one of Cooper’s (since deleted) tweets, just to give you an idea:

This tweet, I think, is illustrative of the thinking on the American right. It would be wrong to say that the Trump movement, or modern National Conservatism, represents a wholehearted endorsement of Nazism. But it should be uncontroversial to say that the American Right views wokeness as a greater threat than the potential return of Hitler.

Why has the legend of Hitler lost its terror? There are several reasons. The generation that fought and defeated the Nazis has largely passed away, meaning that for most Americans, Hitler only exists as a character in movies and books; as with Tamerlane or Genghis Khan, the fear of a mass murderer fades as the centuries pass. The Palestine movement has effectively removed Jews from the Left’s list of protected minority groups whose rights might be defended with riots. Social media has led to the overuse of the Nazi label, leading to the popular phrase “Everyone I don’t like is Hitler”.

Lyons is far more sanguine about this shift than I am. Personally, I think it was a good idea to vilify Hitler. As a general moral principle, “don’t be Hitler” honestly seems pretty solid. And even if your only concern is the might of Western civilization, a man whose ideologically-motivated military campaigns led to the end of European global empires1, slaughtered over 20 million Slavs, ended Germany’s status as a great power, and cemented Soviet rule over half of Europe seems like he should probably serve as an example to avoid.

But Lyons believes that the end of anti-Nazism as the West’s guiding principle will pave the way for the return of morality, community, rootedness, faith, and civilizational pride — the kind of things conservatives like:

Hugely influential liberal thinkers like Karl Popper and Theodor Adorno helped convince an ideologically amenable post-war establishment that the fundamental source of authoritarianism and conflict in the world was the “closed society.” Such a society is marked by what Reno dubs “strong gods”: strong beliefs and strong truth claims, strong moral codes, strong relational bonds, strong communal identities and connections to place and past – ultimately, all those “objects of men’s love and devotion, the sources of the passions and loyalties that unite societies.”

Now the unifying power of the strong gods came to be seen as dangerous, an infernal wellspring of fanaticism, oppression, hatred, and violence. Meaningful bonds of faith, family, and above all the nation were now seen as suspect, as alarmingly retrograde temptations to fascism…

Instead of producing a utopian world of peace and progress, the open society consensus and its soft, weak gods led to civilizational dissolution and despair. As intended, the strong gods of history were banished, religious traditions and moral norms debunked, communal bonds and loyalties weakened, distinctions and borders torn down, and the disciplines of self-governance surrendered to top-down technocratic management. Unsurprisingly, this led to nation-states and a broader civilization that lack the strength to hold themselves together, let alone defend against external threats from non-open, non-delusional societies. In short, the campaign of radical self-negation pursued by the post-war open society consensus functionally became a collective suicide pact by the liberal democracies of the Western world.

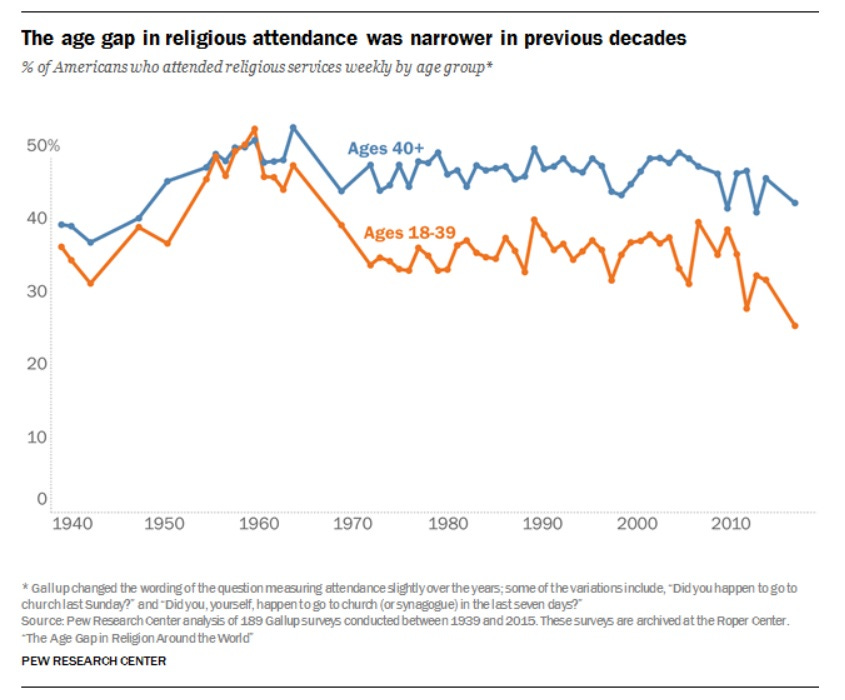

I’m not quite so sure about Lyons’ reading of history here. After all, as Robert Putnam chronicled in his book The Upswing, the postwar decades in America saw the greatest surge in church attendance, civic participation, family formation, and social solidarity since the early days of the Republic. Here’s church attendance, which surged after World War 2 and remained high for people over 40 until the 2010s:

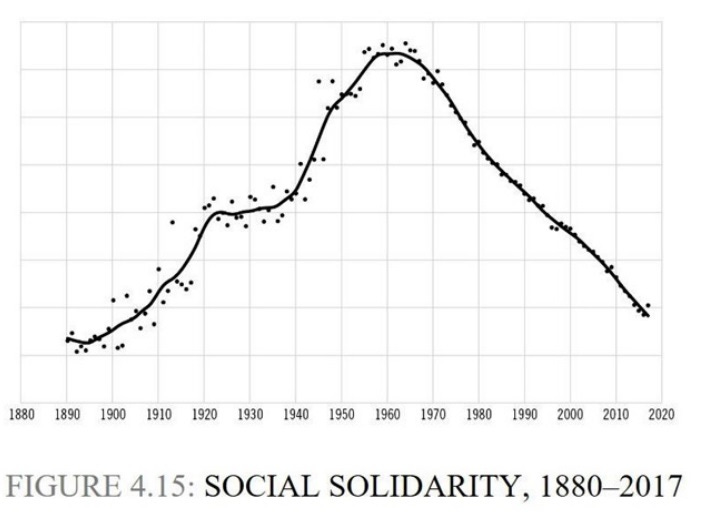

And here’s Putnam’s index of social solidarity, which combines measures of civic and religious participation and family formation:

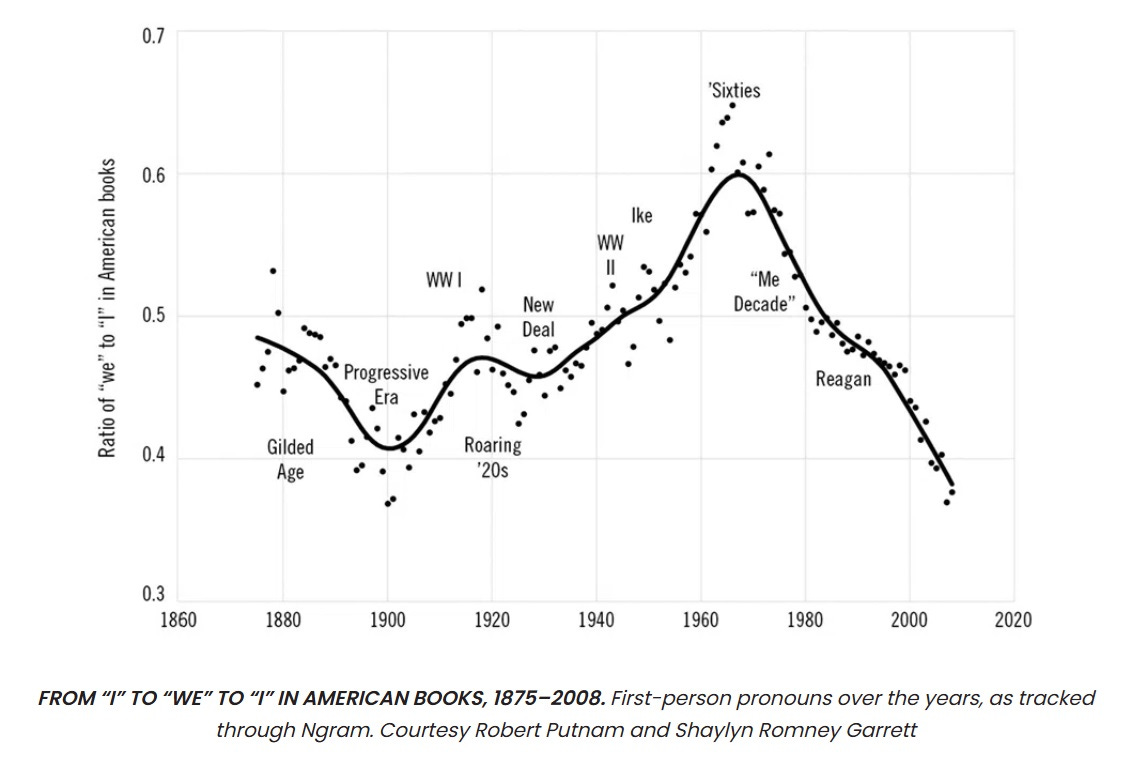

The New Deal and the postwar period even saw a huge upswing in the use of the word “we” instead of the word “I” in American books:

The “strong gods” were never stronger than they were among the generation of Americans who grew up listening to FDR preach liberalism on the radio and who went on to crush Adolf Hitler into the dust. Nor is it difficult to draw a causal line between the unifying struggle of the Second World War and the great American unity that followed.

The Greatest Generation believed with all their hearts that Hitler was Satan on Earth. But they did not believe that family, community, and tradition were little Hitlers that needed to be crushed in order to uphold the open society. Indeed, their society was both open and deeply rooted. My grandparents knew the names and the life stories of every one of their neighbors until the day they died; how many “national conservative” intellectuals and diehard Trump fans can say the same?

But in any case, the “strong gods” did eventually wane in America. Lyons believes that Trump is bringing them back:

Mary Harrington recently observed that the Trumpian revolution seems as much archetypal as political, noting that the generally “exultant male response to recent work by Elon Musk and his ‘warband’ of young tech-bros” in dismantling the entrenched bureaucracy is a reflection of what can be “understood archetypally as [their] doing battle against a vast, miasmic foe whose aim is the destruction of masculine heroism as such.” This masculine-inflected spirit of thumotic vitalism was suppressed throughout the Long Twentieth Century, but now it’s back…

Today’s populism is…a deep, suppressed thumotic desire for long-delayed action, to break free from the smothering lethargy imposed by proceduralist managerialism and fight passionately for collective survival and self-interest. It is the return of the political to politics. This demands a restoration of old virtues, including a vital sense of national and civilizational self-worth…

This is what Trump, in all his brashness, represents: the strong gods have escaped from exile and returned to America…Trump himself is a man of action, not rumination…He is…an embodiment of the whole rebellious new world spirit that’s now overturning the old order…The very boldness of [Trump’s] action reflects more than just partisan political gamesmanship – in itself it represents the stasis of the old paradigm being upended; now “you can just do things” again.

The word “thumotic” here refers to Harvey Mansfield’s use of the Greek word “thumos” to mean a sort of political passion and drive. Francis Fukuyama spelled it “thymos”, and even predicted in 1992 that Donald Trump might be the perfect embodiment of Americans’ thymotic urge to tear down the liberal establishment.

Lyons thus sees Trumpism as a sort of Fight Club style reassertion of wild, unapologetic, masculine drive — only instead of directing it toward anarchism like Tyler Durden, Lyons sees Trump and Musk indulging their manly passion in the dismantling of the civil service.

But Lyons never explains exactly how this destructive impulse will bring back the return of the “strong gods” he yearns for. He sees the civil service and other American postwar institutions as obstacles to the revitalization of rootedness, family, community, and faith, but he doesn’t really look beyond the smashing of those supposed obstacles toward the actual rebuilding. He just sort of assumes it will happen, or that it’s a problem for another day.

I believe he’s headed for disappointment. Trump’s movement has been around for a decade now, and in all that time it has built absolutely nothing. There is no Trump Youth League. There are no Trump community centers or neighborhood Trump associations or Trump business clubs. Nor are Trump supporters flocking to traditional religion; Christianity has stopped declining since the pandemic, but both Christian affiliation and church attendance remain well below their levels at the turn of the century. Republicans still have more children than Democrats, but births in red states have fallen too.

In Trump’s first term, the attempts at organized civic participation on the Right were almost laughably paltry. A few hundred Proud Boys got together and went to brawl with antifa in the streets of Berkeley and Portland. There were a handful of smallish right-wing anti-lockdown protests in 2020. About two thousand people rioted on January 6th — mostly people in their 40s and 50s. And none of these ever crystallized into long-term grassroots organizations of the type that were the norm in the 1950s.

For a very few people, the first Trump term was a live-action role-playing game; for everyone else, it was a YouTube channel.

And in Trump’s second term so far? Nothing. Even the rally numbers are way down. National conservatives who might have gone out to meet each other in 2017 are hunkering at home alone in their living rooms, swiping back and forth between X and OnlyFans and DraftKings, pumping their fists in the air as they read about how Elon Musk and his band of computer nerds are firing people or Trump is cutting off aid to Ukraine. “You can just do things”, except almost zero of Trump’s supporters are actually doing anything except passively cheering for their notional team. Unless you’re one of the tiny group of nerds helping Elon Musk dismantle the bureaucracy, the thumos is all secondhand.

The MAGA movement, you see, is an internet thing. It’s another vertical online community — a bunch of deracinated, atomized individuals, thinly connected across vast distances by the notional bonds of ideology and identity. There is nothing in it of family, community, or rootedness to a place. It’s a digital consumption good. It’s a subreddit. It is a fandom.

N.S. Lyons and the national conservatives have entirely misapprehended the cause of America’s abandonment of rootedness, community, family, and faith. We didn’t abandon those “strong gods” because liberals went too hard on old Adolf. We abandoned them because of technology.

The 1920s saw the beginning of mass affluence in America, along with the creation of technologies that gave individual human beings unprecedented autonomy and control over their physical location and their information diet. Car ownership allowed Americans to go anywhere, any time, freeing them from their ties to a specific place. Telephone ownership let people communicate over vast distances. Television and radio exposed them to new ideas and cultures, and the internet exposed them to even more.

Then came social media and the smartphone. Suddenly, “society” didn’t mean the people in the physical space around you — your neighbors, coworkers, workout buddies, etc. First and foremost, “society” became a collection of avatars writing text to you on a little glass screen in your pocket. Your phone was where you met and conversed with friends and lovers, where you argued about politics and ideas. People’s roots changed from physical space to digital space.

There is a slowly building mountain of evidence connecting phone-enabled social media to feelings of isolation and alienation, to solitude and loneliness, to declining religiosity, to reduced family formation and lower birth rates. American society became somewhat disconnected by the introduction of the 20th century technologies of the car, the telephone, the TV, and the internet, but it managed to partially resist and preserve some remnant of rootedness. But phone-enabled social media broke through those last walls of resistance and turned us into free particles floating in a disembodied space of memes and identities and distractions.

The strong gods turned out to be weaker than the new gods made of silicon.

The people who did this were more or less the same people N.S. Lyons is now cheering on. It wasn’t Elon Musk himself, of course; he just made cars and rockets. But it was Steve Jobs, Jack Dorsey, Zhang Yiming, and a bunch of other entrepreneurs who followed their thumos toward vast riches by building the virtual world that has become our truest home.

I am not saying they were evil to do this. Technology has a way of progressing, especially in advanced societies; if it can be done, it probably will be done. And no one could have known about the downsides ahead of time. But it is a bit ironic that the class of people whom N.S. Lyons now believes will usher in a new age of rootedness and community is the exact same class of people who destroyed the old one.

But anyway, yes, this thing will fail, because nothing is being built. Yes, every ideological movement assures us that after the old order is completely torn down, a utopia will arise in its place. Somehow the utopia never seems to arrive. Instead, the supposedly temporary period of pain and sacrifice stretches on longer and longer, and the ideologues running the show become ever more zealous about blaming their enemies and rooting out the enemies of the revolution. At some point it becomes clear that the promises of utopia were just an excuse for the rooting out of enemies — thumos as an end in and of itself.

Already, Trump’s Treasury Secretary is telling us that the economic pain Trump is causing is just a “de-tox period”, Trump is blaming “globalists” for the fall in the stock market, and Trump’s Justice Department is blaming egg prices on hoarders and speculators. If you don’t recognize this plot line, you must not read much news or much history.

Smashing the old order does not, in itself, create anything at all. The Visigoths and the Vandals built nothing on top of the ruins of Rome. They indulged their thumos and scampered away to feast for a while on the wealth they looted, and then they disappeared into myth and memory.

Over the past decade and a half I’ve watched in dismay as the real-world communities and families I knew in my youth got ripped up and replaced with a collection of imaginary online identity movements. I’m still waiting for someone to figure out how to put society back together again — how to do what FDR and the Greatest Generation did a century ago. Looking at the Trump movement, I’m pretty sure this isn’t it.

The fact that Hitler effectively brought down the British Empire explains his strangely enduring popularity in parts of South Asia.

Lyons' essay seems like yet another example of the sort of overwritten, pompous positing that has become a hallmark of Trumpist apologist-intellectuals.

It seems pretty obvious to me that in just about any other era, Trump would be recognized as the fraud, huckster, and ignoramus he so obviously is. He's a product of a tawdry late-20th century entertainment tabloid culture that nevertheless managed to seduce a lot of people. He's no man of action, nor any sort of epoch-defining figure, and the fact that he's hated by half the country doesn't prove it, though men like Lyons like to think it does. Sometimes people are just hated because they're awful, and sometimes the damage they wreak is just damage.

This is a great essay, Noah. "You didn't build anything." is a good meme for the 2028 election. Kudos to you.