The Clean Little Secret of Social Security

It’s a pretty good program, and we can afford it

Social Security is in the crosshairs of the Musk/Trump administration. First Musk came out with the claim that tens of millions of dead people are still receiving benefits. This claim has been thoroughly debunked, but still made its way into deputy president Trump’s big speech Tuesday. Then Musk began declaring that the 90-year-old program is a Ponzi scheme.

The first claim seems to reflect the fact that the Dunning-Kruger kids — the mostly very young staffers DOGE sent into the Social Security Administration, too incompetent to see their own incompetence — didn’t know how to interpret SSA databases. The second claim showed that Musk doesn’t understand what Social Security is or how it works.

To be fair, however, Musk isn’t alone in his lack of understanding, although he may be unique in his combination of arrogance and ignorance. So I thought I’d devote this week’s primer to the basics of Social Security. Beyond the paywall you’ll find:

1. How Social Security works from workers’ point of view

2. How it’s financed

3. Why the challenge of keeping the system going isn’t as hard as you think

How Social Security works

If you work for someone else, as most of us do, your pay stub shows your gross salary with a deduction for FICA — short for the Federal Insurance Contributions Act. Part of this deduction is for Medicare, which I won’t talk about today. But 6.2 percent of your paycheck, up to a maximum of $176,100, goes to Social Security, matched by an equal contribution from your employer. Only 6 percent of workers earn more than that maximum, so the great majority of workers contribute 12.4 percent of their earnings to Social Security. In return, they start receiving benefits once they reach a certain age — 62 if they’re willing to accept reduced benefits, 67 if they want full benefits.

To a casual observer, Social Security looks like an old-fashioned pension plan: you pay in during your working years, then get money back once you reach retirement age. And there’s a good reason Social Security looks that way: When FDR created the system he wanted it to look like a private-sector pension plan, in order to avoid criticism that it was “socialist.”

While there are important features of Social Security that are like a private pension plan, there are two very important differences.

Like a private pension plan, Social Security benefits do depend on how much you earned, and hence how much you contributed, during your working years. In fact, that’s the only thing that matters. The Social Security system is remarkably unintrusive into your personal life: the system doesn’t ask for proof that you need the money, it just pays out.

But, unlike a private pension plan, the relationship between what you contribute into Social Security and what you get out isn’t one-for-one. There is, in fact, some redistribution of income within Social Security. Americans who earned very low wages get most of those wages replaced by SS benefits. But high earners are treated much less generously.

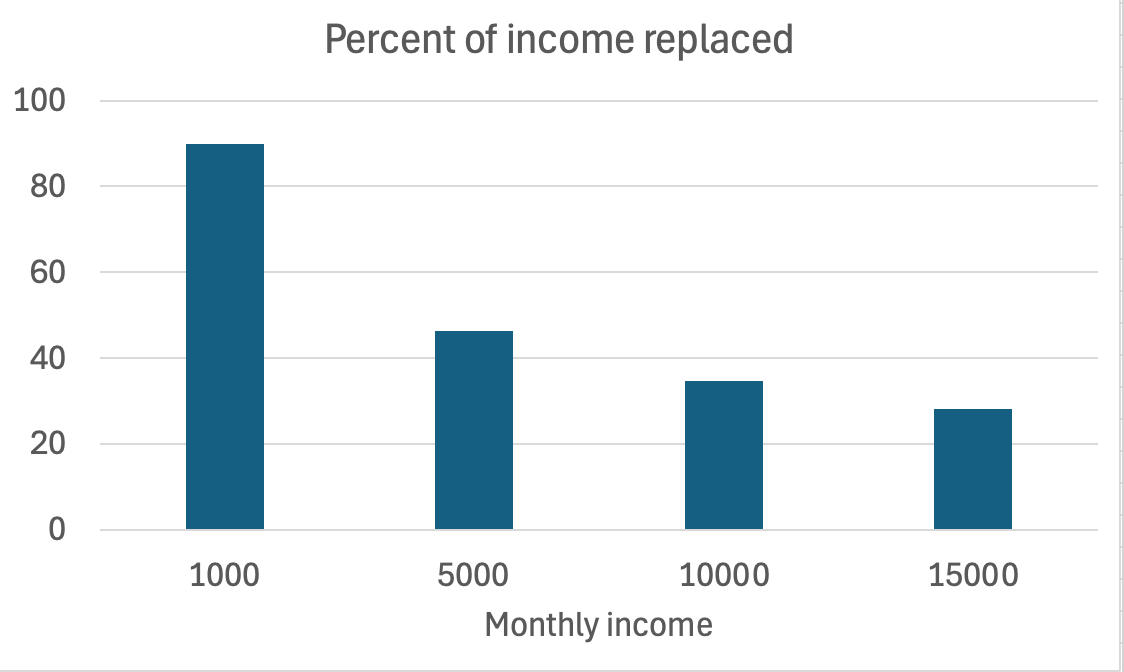

Here’s the relationship between monthly earnings while you were working and the percentage of those earnings replaced in 2025:

If this makes Social Security look like a much better deal for low-wage workers, that’s because that is, in fact, the intention: The program was quietly designed to be progressive, helping low-wage workers much more than higher-wage workers. And one of the clean little secrets of Social Security is it has worked very well to achieve that objective: poverty among the elderly, which used to be pervasive, has been almost completely eliminated.

The second way that Social Security differs from an ordinary pension plan is that it is backed by relatively few assets in comparison to its obligations. Most of today’s retirement plans are “defined contribution”, in which your employer is only obligated to put a certain money into an investment account to fund your retirement. However many workers still have traditional “defined benefit” plans, in which you are owned a fixed amount every month for your retirement. Defined benefit plans are legally required to hold enough assets to cover their expected future payments -- even if the company offering the plan goes bankrupt.

Social Security, however, has “only” $2.7 trillion in assets. That can sound like a big number, but we’re talking about a very big system. If it had to rely solely on those assets to pay benefits, the system would run out of money in less than two years.

Therefore, in order to meet its obligations, Social Security depends on the continuing inflow of money from FICA -- that is, payments into the system by current workers. Presumably Elon Musk is aware of this fact, leading him to call Social Security a “Ponzi scheme.”

In typical fashion, Musk apparently didn’t check with anyone who understands Social Security before pronouncing it to be a fraud. If he had checked, he would have learned that Social Security really isn’t a pension fund. It is, instead, a government program supported by a dedicated tax — one of many examples of that practice, although Social Security is the biggest.

Paying for Social Security

Governments collect money through a variety of taxes. At the federal level the big ones are the personal income tax, the corporate profits tax, and payroll taxes — because that’s what FICA really is. At the state and local level the mix includes income taxes in some but not all states, sales taxes and property taxes.

Governments also spend money on a variety of things. At the federal level, the main categories are retirement (Social Security), health care (Medicare and Medicaid) and defense. At the state and local level the big items are education and law enforcement.

The simplest way to think about government finances — and also, for most purposes, the right way to think about them — is to imagine everything going into or coming out of one big pot of money. Taxes put money in, while government programs take money out.

What if the money going out exceeds the money coming in? Then the government borrows to cover the difference. Sometimes that borrowing is a good thing, helping to boost a depressed economy. Sometimes it’s a bad thing, diverting funds that the private sector might have put to productive use. And even deficit doves like myself worry that under certain conditions governments may borrow enough to raise concerns about their solvency.

I wrote about those issues two weeks ago. But to understand the Social Security discussion you need to know that the one-pot picture of government finance is a bit oversimplified. Why? Because governments sometimes link particular taxes to particular programs.

Most revenue goes into a common pot, and most spending comes out of that pot. But some taxes are dedicated to specific programs, which therefore have their own sub-budgets.

A fairly familiar and, I hope, not too controversial example is the Highway Trust Fund. Federal taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel, plus some smaller vehicle-related taxes, are used to pay for spending on highways and mass transit.

Why assign certain taxes to certain programs? Basically, it’s about politics. It’s easier to get voters to accept new taxes or tax increases if they’re explicitly connected to paying for something people want. To take a recent example, New York’s new congestion charge is mainly intended to reduce congestion (duh), but it’s also a new revenue source, and the plan was sold partly by linking the new revenue to investment in improving public transit.

Now, the separation of individual programs from the general budget is a lot less rigid in practice than it may look in a stylized picture. In particular, it’s quite common to “top up” important programs if their dedicated revenue sources seem inadequate. For example, over the past couple of decades Congress has repeatedly allocated additional funds for transportation infrastructure over and above the money raised by fuel taxes. But such allocations require new legislation, while using money from dedicated taxes doesn’t, so it would be wrong to say that the system of dedicated taxes is meaningless.

Which brings us to Social Security, which is supported by FICA — a tax levied on everyone’s wages.

People like Musk seem to imagine that workers putting money into Social Security are like, say, small investors buying $Trump coins, whose naivete is the only thing allowing earlier investors to cash out. But paying payroll taxes isn’t a voluntary individual decision; like paying gas taxes at the pump, it’s the law. And there’s no reason in principle why Social Security couldn’t be run indefinitely on a pay-as-you-go basis, with taxes on current workers paying for retirees’ benefits. In fact, that’s more or less how the system was run until the 1980s.

By 1980, however, it was obvious that some adjustments would have to be made. Why? Because the baby boomers were getting older.

The demographic challenge

After World War II the soldiers came home, the economy boomed, the suburbs opened up and Americans had lots of children. The Baby Boom is generally considered to have run from 1946 to 1964.

Children eventually become working-age adults. Working-age adults, however, eventually become seniors, who collect Social Security benefits.

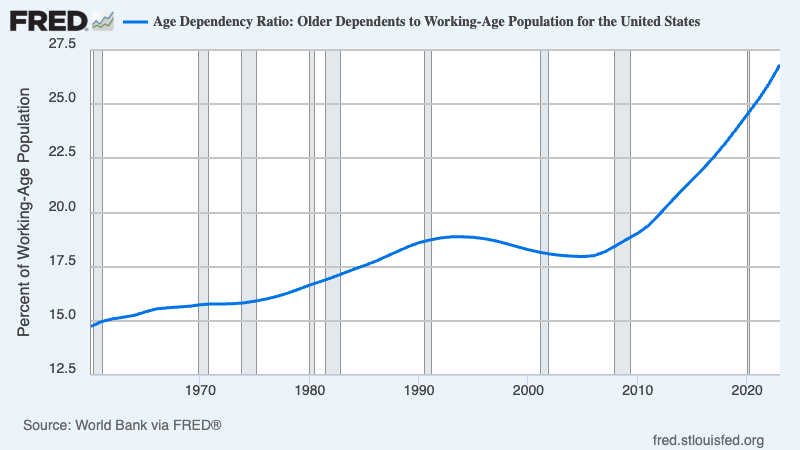

So there was a surge in the “old-age dependency ratio,” the share of adults over 65, as the leading edge of the baby boom hit retirement age:

This created an obvious financing problem for a program that provides benefits to seniors, supported by a tax on workers. However, this was a problem everyone paying attention saw coming decades in advance. So Ronald Reagan convened the National Commission on Social Security Reform, generally referred to as the Greenspan Commission, to head off the predictable financing problem.

Following the Commission’s recommendations, Congress increased FICA and also set in motion a gradual rise in the full-benefits retirement age. You can see, by the way, what I mean about the political advantages of dedicated taxes. If Reagan had simply said, “Now that I’ve given big tax cuts to high earners, I’m going to raise taxes on ordinary workers,” there would have been a major backlash. But what he actually said was, in effect, I’m increasing contribution rates to secure the future of Social Security, and the public went along.

The purpose of these changes was to enable Social Security to run substantial surpluses during the years when boomers were still working and not collecting benefits. The accumulation of these surpluses created a substantial Social Security trust fund, which peaked in 2020 at $2.9 trillion and is still, as we’ve seen, $2.7 trillion.

Is this trust fund “real”? No and yes. It consists entirely of U.S. government debt, which means that it’s just claims by one part of the government on the rest of the government. So you could say that it’s just an accounting fiction. But it has important legal and political implications. We’ve now reached the point where benefit payments are bigger than revenue from FICA. But for now, the Social Security Administration can maintain payments by drawing on the trust fund, with no immediate need for legislation to bail the system out.

The Greenspan Commission’s reforms were originally intended to keep the system running without additional interventions until 2060. This almost certainly won’t happen; at this point it looks as if the trust fund will be exhausted around 2034 or 2035. The main reason for the shortfall is rising inequality: a growing share of wages are going to people making more than the Social Security maximum, and income above the maximum isn’t taxed.

In any case, once the trust fund is gone, something will have to happen. No, Social Security won’t go “bankrupt.” Even with the trust fund gone, payroll tax receipts will still cover 77 percent of scheduled benefits. But seniors would, understandably, be furious if their benefits were suddenly cut.

So the most likely outcome — or at least that’s my guess — is that Congress will find a way to provide Social Security with more money. One obvious way to do this would be to raise, maybe even eliminate, the FICA maximum. Only 6 percent of workers earn more than that maximum, but some of them earn a lot more, so this would raise a substantial amount.

I’m not wedded to this solution; one problem with it is that high-income Americans get a lot of their money from investment income, which an extended payroll tax wouldn’t touch. But one way or another, we should keep Social Security going, not with harsh benefit cuts, but by finding money to fill the gap once the trust fund is exhausted.

But can we afford to sustain Social Security in the face of an ever-aging population? Yes.

It sometimes seems to me as if discussions about Social Security are caught in a time loop where it’s always 2005, and Very Serious People issue ominous warnings about what will happen when the gray wave of baby boomers hits the system. But it’s 2025, and they (we) are already here. Most of the fiscal impact of an aging population is already in the budget numbers.

And the other clean little secret of Social Security is that it won’t be too hard to absorb what’s left of that impact, given the political will.

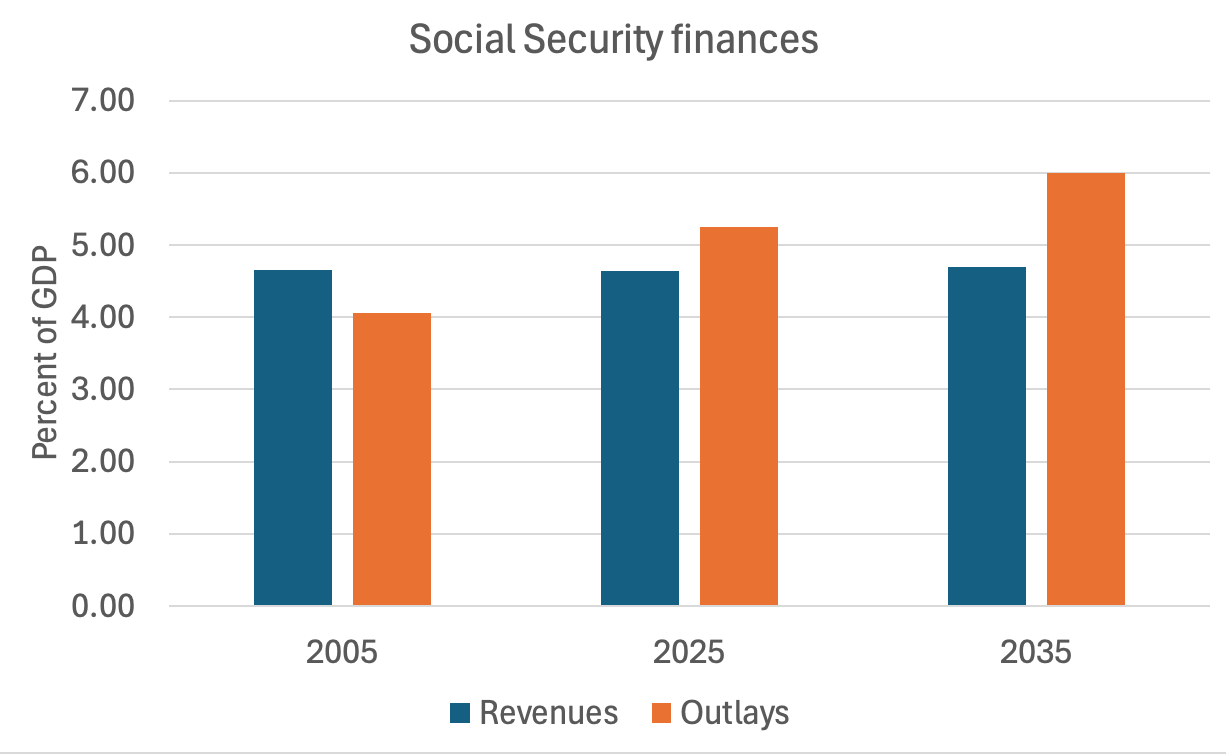

Here’s a comparison of Social Security revenues and outlays in 2005, when George W. Bush tried to use dire warnings about the future to privatize the system; right now; and 2035, which looks like the year the trust fund will be exhausted:

As you can see, the system has in fact moved from surplus to deficit, and will move somewhat deeper into deficit over the next decade as the last of the baby boomers start collecting. And maintaining full benefits beyond that point will require finding a significant amount of money — 1.3 percent of GDP — a sum that will grow, but only a little, over time.

The question you should ask is, how big is 1.3 percent of GDP? It’s not a trivial number, but it’s not a crushing burden either.

Here’s a point of comparison: House Republicans just passed a budget resolution calling for $4.5 trillion in tax cuts, mainly for the wealthy, over the next decade. If we compare those cuts with CBO economic projections, they amount to … 1.2 percent of GDP.

So roughly speaking we could raise enough money to sustain Social Security as it is simply by not letting Republicans cut taxes for the rich. OK, I know that we would have a deficit problem even without those tax cuts. But you can’t simultaneously support the G.O.P.’s tax agenda and claim that Social Security is in desperate financial straits, which can only be solved with radical cuts or privatization.

There’s a lot more I’d like to say, but this primer is already long, so I’ll save it for future posts. For now, let me leave you with three key points:

1. Social Security isn’t a Ponzi scheme or a scam; it’s just a government program supported by a dedicated tax, which is perfectly normal

2. It’s a highly successful program, which has vastly improved older Americans’ lives

3. It faces a financial shortfall, but the shortfall isn’t that big, and sustaining Social Security is well within America’s means.

Above all, don’t let Elon Musk and his kids panic you into thinking that we must destroy Social Security to save it.

Paul, as a paying subscriber I do not have a problem if this post is made available to the wider audience. You must. People, especially fellow paying subscribers, LIKE if you agree.

Thank you for this excellent primer, delivered calmly and clearly with no hyperbole. Much appreciated.