Tasks Versus Skills Part 2: Seven Playbook Takeaways on How to Win with AI, Tasks, and Skills

A 7-part position paper and eBook on the state of tasks versus skills, a playbook, and some provocative what-if concepts for task-enabled Learning and Development, and Talent teams.

This is Part 2 of a series called Tasks Versus Skills: Part 1: Introduction, Part 2: Playbook, Part 3: Let Learning Breathe, Part 4: Task Intelligence Control Room, Part 5: Tasks as EX Product, Part 6: IQA Prototype, Part 7: Talent Is Not a Commodity; Google Books “Tasks vs Skills” free ebook (Parts 1-6 only).

As we navigate the evolving landscape of AI, tasks, and skills in the workplace, it's crucial to have a practical approach. The following seven playbook takeaways offer a comprehensive guide to leveraging these elements for organizational success. Each takeaway provides actionable insights and strategies to help you integrate AI, optimize task management, and develop essential skills in your workforce.

1. CLARIFY YOUR TAXONOMY, ONTOLOGY AND SKILLS FRAMEWORK APPROACH

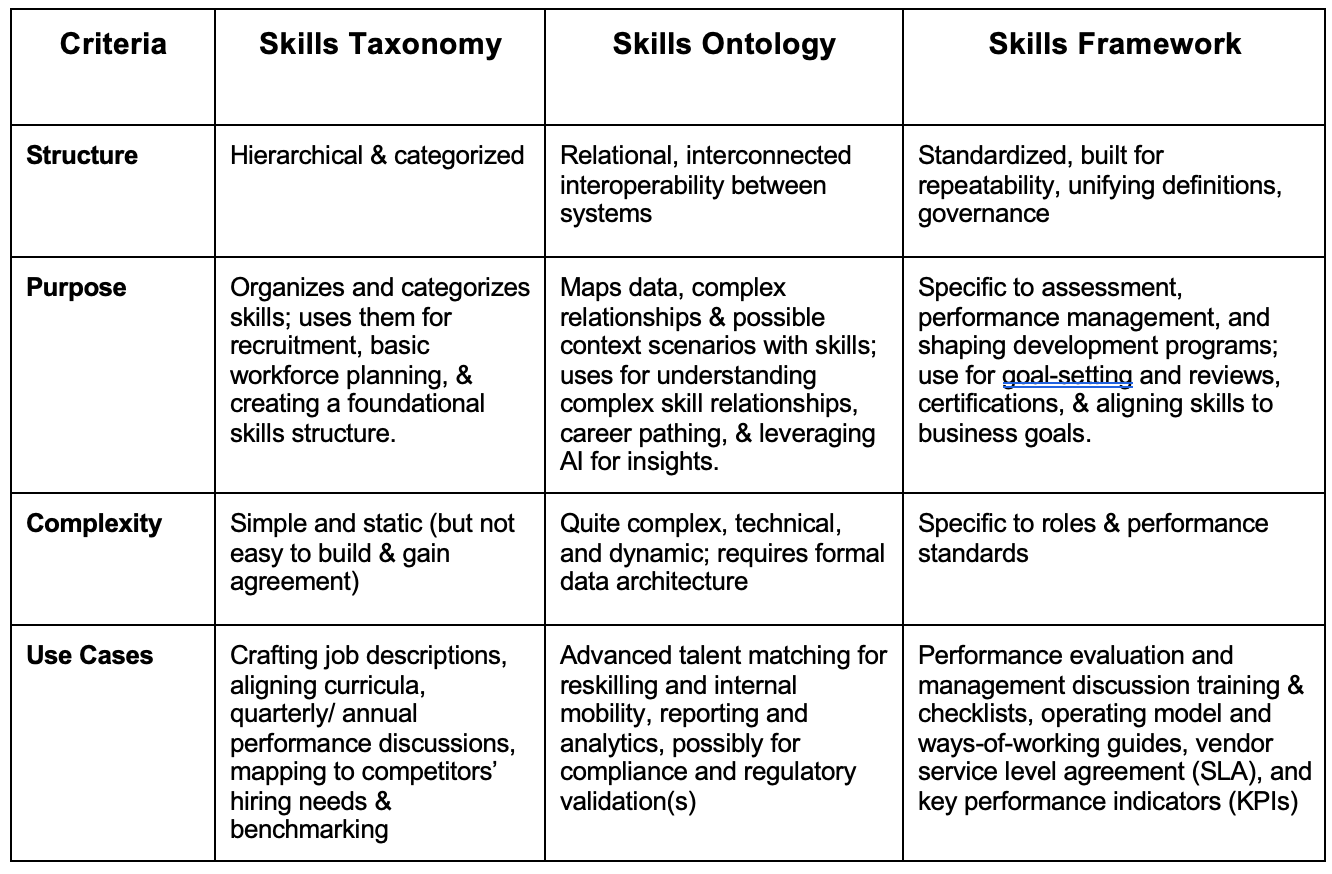

Let’s get grounded on some core definitions to understand and differentiate as you’re crafting a Skills + Tasks strategy:

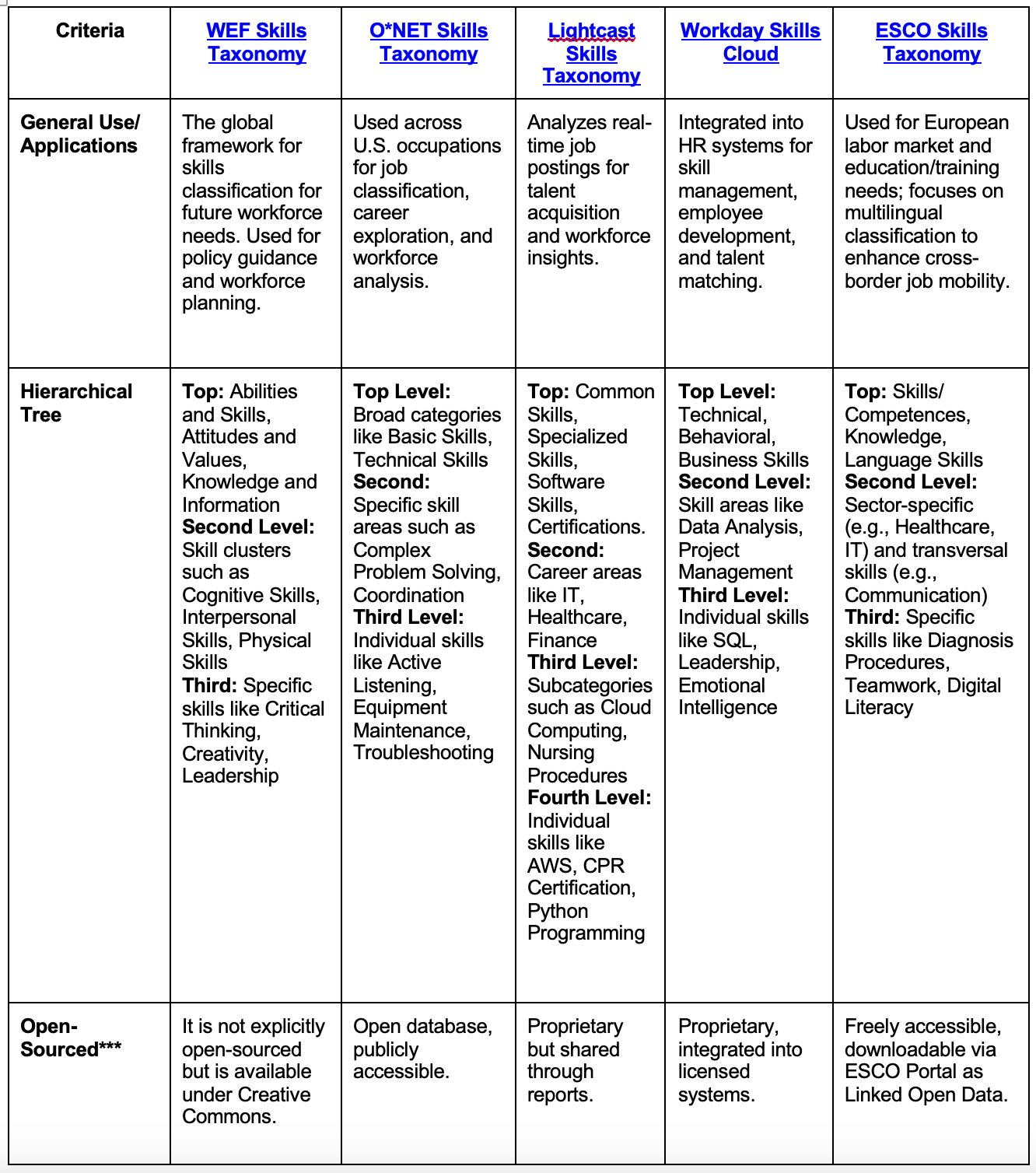

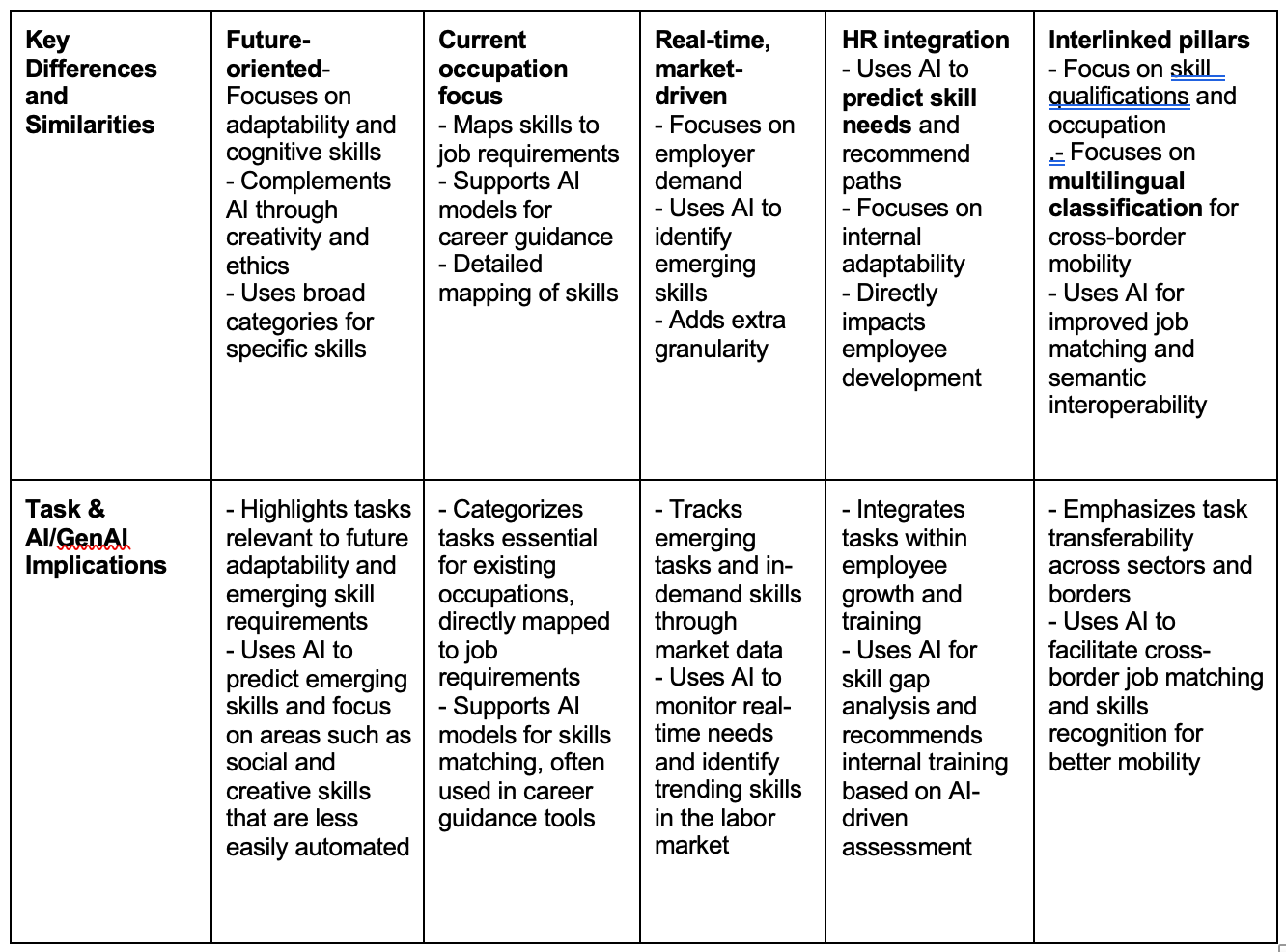

Skills Taxonomy: As shared previously, skills taxonomy is a hierarchical system used to classify and categorize an organization’s skills into broad groups and sub-skills. There are several types of skills taxonomies for different uses and purposes, as highlighted in the Appendices. (See Appendix C)

Skills Ontology: A skills ontology extends beyond taxonomy classification so you can map relationships across varied skills and incorporate more sophisticated tagging to facilitate interoperability across platforms and data storage systems.

Skills Framework: Generally, a skills framework acts as a unique set of guidelines or a playbook of sorts aligning skill methods (taxonomy and ontology, possibly business use cases, roles, functions…) for each company and is typically managed by the HR, Talent and/or L&D teams.

(See Appendix D for in-depth descriptions)

The need for more open-sourced taxonomy solutions is vital as well. There are a few open source bodies or authorities to guide us, including the Open Source Initiative (OSI), Creative Commons, The Open Definition (Open Knowledge Foundation), and the Linux Foundation. Why is this standard important for skills and tasks?

An open-sourced skills taxonomy provides a standardized framework and common language for skills across organizations, industries, and even countries. This standardization facilitates better communication and understanding of skills requirements among employers, educators, and job seekers.

Being open source means the taxonomy is freely available for use, modification, and improvement by anyone (though guidance by the above authorities remains critical). This encourages collaboration and allows for continuous refinement of the taxonomy based on input from various stakeholders.

Also, researchers, policymakers, and organizations can use the open-source taxonomy to conduct more accurate and comprehensive analyses of labor market trends, skill demands, and workforce capabilities.

And benefits of open sourced taxonomies with an optimized AI:

This standardization allows AI systems to more easily process, categorize, and analyze skills and task data from diverse sources.

This leads to better training datasets for AI models, resulting in more accurate predictions and insights.

Open source taxonomies provide large, standardized datasets that can be used to train AI and machine learning models, leading to more effective skills matching, gap analysis, and workforce planning.

An open-source taxonomy can serve as a ‘universal adapter’ for existing frameworks, allowing AI systems to more easily integrate and compare skills data across different platforms and organizations.

Lastly, whether or not you follow any open source criteria for your strategy, keep in mind a gold standard that any ‘compliant’ taxonomy provider should include, which is the Four Essential Freedoms as defined by the GNU General Public License. While the Four Freedoms are more inclined to software development needs, the complement with taxonomies resonates, especially given AI’s scale and diverse applications. The Four Freedoms:

Freedom to run the program for any purpose

Freedom to study and modify the program's source code

Freedom to redistribute copies of the original program

Freedom to distribute modified versions of the program.

With this understanding–especially again with cross-functional teams who may be operating with different definitions–your approach will drive clarity and ideally level-set expectations for planning and budgeting needs.

Considerations for your Taxonomy approach:

If you have a skills taxonomy or similar already in place, one that is already embedded in various programs, one that is already integrated into your Learning, Talent, and people systems, keep it. This is already a gift. With this already in place, it’s much easier to list complementary tasks with each skill versus starting from scratch.

Your approach to communicating and gaining buy-in with your skills strategy starts with socializing and enforcing common definitions broadly (e.g., skill definition, proficiency, what’s a competency compared with a capability…). Additionally, the definition of a ‘taxonomy’ may vary, especially when comparing ‘ontology’ and ‘framework’ definitions from vendors’ content libraries and legacy HR and learning systems.

Is there an open-source advocate or team at your company? Reach out for an informal coffee/tea and gain their opinion as it relates to skills and tasks. Building a coalition will take you further than you think.

2. MONITOR THE TASKONOMY AND TASKOLOGY MOMENTUM

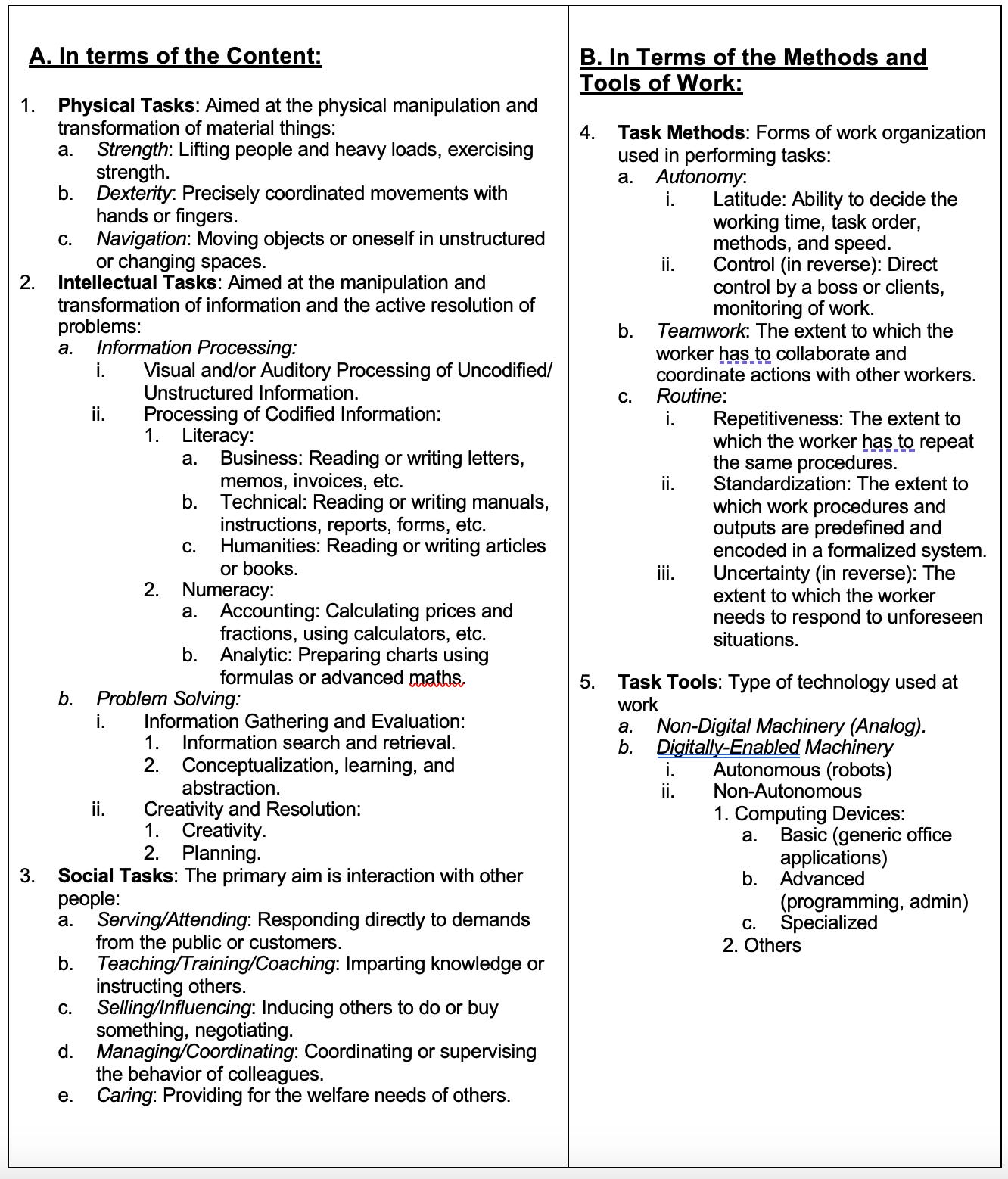

If you want to go into the deeper depths of taxonomies, Enrique Fernández‑Macías and Martina Bisello highlight in “A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Tasks for Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on Work” a more modern hierarchical classification. "Our [work on a task-centric] framework connects the material content of work (what people do at work, with tasks classified according to the type of object and transformation processes) with its organizational form (how people coordinate their work)." [19]

Note how this “taskonomy” approach provides a broader perspective compared to a skill taxonomy, which mainly focuses on the capabilities of workers without considering how their work is structured. Unlike a more traditional hierarchy of skill categories (e.g., broad or common skills to individual or specialized…), Fernández‑Macías and Bisello’s approach relies more on the actual action or discreet activities that occur throughout a workflow as compared with taxonomies like O*NET’s Basic and Technical skill categories, or perhaps WorkDay’s Technical, Behavioral and Business skills hierarchy.

Here’s Fernández‑Macías and Bisello’s taskonomy approach or five key categories with a detailed framework:

Physical Tasks: Activities aimed at manipulating and transforming material things, typically requiring physical effort, coordination, and movement.

Intellectual Tasks: Activities involving modification, transformation of information, and problem-solving.

Social Tasks: Activities primarily aimed at interacting with others.

Task Methods: Describes how work is carried out and organized.

Task Tools: This category refers to the equipment and technology used to carry out work tasks.

(See Appendix E for taskonomy detail)

The development of task taxonomies can provide valuable insights into work processes, facilitate job redesign, and support strategic workforce planning that will clarify or augment human tasks and Agentic AI tasks.

Again, the need for a proportional Task + Skill understanding and approach.

Taskonomy considerations:

Do you have a team focused on Strategic Workforce Planning or analyzing the labor market? If so, task taxonomies will increase their value, given that tasks have more portability across jobs and the work itself, as well as AI and other technology’s ability to identify routine activities. As researchers Taluk and Jacobs share, “Whereas the level of skills is an attribute of workers, the level of routine is an attribute of the jobs themselves. Thus, this concept paved the way for a new approximation to labor market analysis... Since technologies are applied in specific production processes, and the labor input in those processes can be classified according to the type of tasks carried out, this approach allows for a much more direct linking of technical change and its employment impact". [20]

Stay informed on any progression regarding similar or potential Task Taxonomies in your company. If there seems to be momentum for a complementary or replacing ‘catalog,’ use this momentum as a more modern or innovative approach that is quantifiable, and may you craft more Performance-Based Training scenarios [see #5 below], learning assessment and certifications (task execution versus skill attainment or completions), and the level of learning analytics and insights you need to track and report.

Note Fernández‑Macías and Bisello’s addition or focus on organizational aspects like autonomy, teamwork, and the routine nature of tasks, which are all critical for understanding how work is organized and how susceptible and influential it is to a technological replacement, i.e., automation, work augmentation, etc.

Related, tasks are not typically as visible, known, or captured by our learning management systems (LMS) and learning experience platforms (LXP) in comparison to skills. Tasks, on the other hand, are more obvious and shared at the grassroots level or amongst peers and coworkers doing similar work. When evaluating a new LMS or LXP or related ‘skill-building’ solution, ensure you can modify its Skills Catalog so you can add more discreet tasks. This also applies to knowledge management systems where “task” details such as workflow processes may already be available.

3. REMEMBER, TASKS ARE (MOSTLY) QUANTIFIABLE AND SPECIFIC, SKILLS ARE (MOSTLY) QUALITATIVE AND CONTEXT-DEPENDENT… BUILD AND MEASURE ACCORDINGLY

Tasks are inherently measurable and quantifiable units of work activity, providing a concrete basis for categorization, evaluation, and improvement. This measurability may extend to the frequency of performance, time spent, and direct outputs produced. As Tesluk & Jacobs note in their seminal article “Toward an integrated model of work experience”, measurement priority should lean towards the "amount of times a task has been performed" or "time-based measures" like tenure. [20] Fernández-Macías & Bisello also define tasks as "discrete units of work activity that produce actual output." In their example, a generative AI implementation in customer service increased resolution per hour by 14%, demonstrating the measurable productivity gains from breaking down tasks and automating components. [21]

Unlike tasks, which are generally static and concrete, skills involve qualitative aspects such as complexity, challenge, adaptability, experience, and greater cognitive processing.

On the other hand, skills represent a broader, more complex set of capabilities that involve qualitative aspects such as adaptability, cognitive processing, and emotional intelligence, making them inherently more fluid and context-dependent compared to tasks. Unlike tasks, which are static and concrete, skills involve qualitative aspects such as complexity, challenge, adaptability, experience, and greater cognitive processing. Skills often represent the underlying capabilities that enable effective task performance across various scenarios, including both cognitive abilities (like problem-solving or critical thinking) and non-cognitive traits (such as emotional intelligence or leadership).

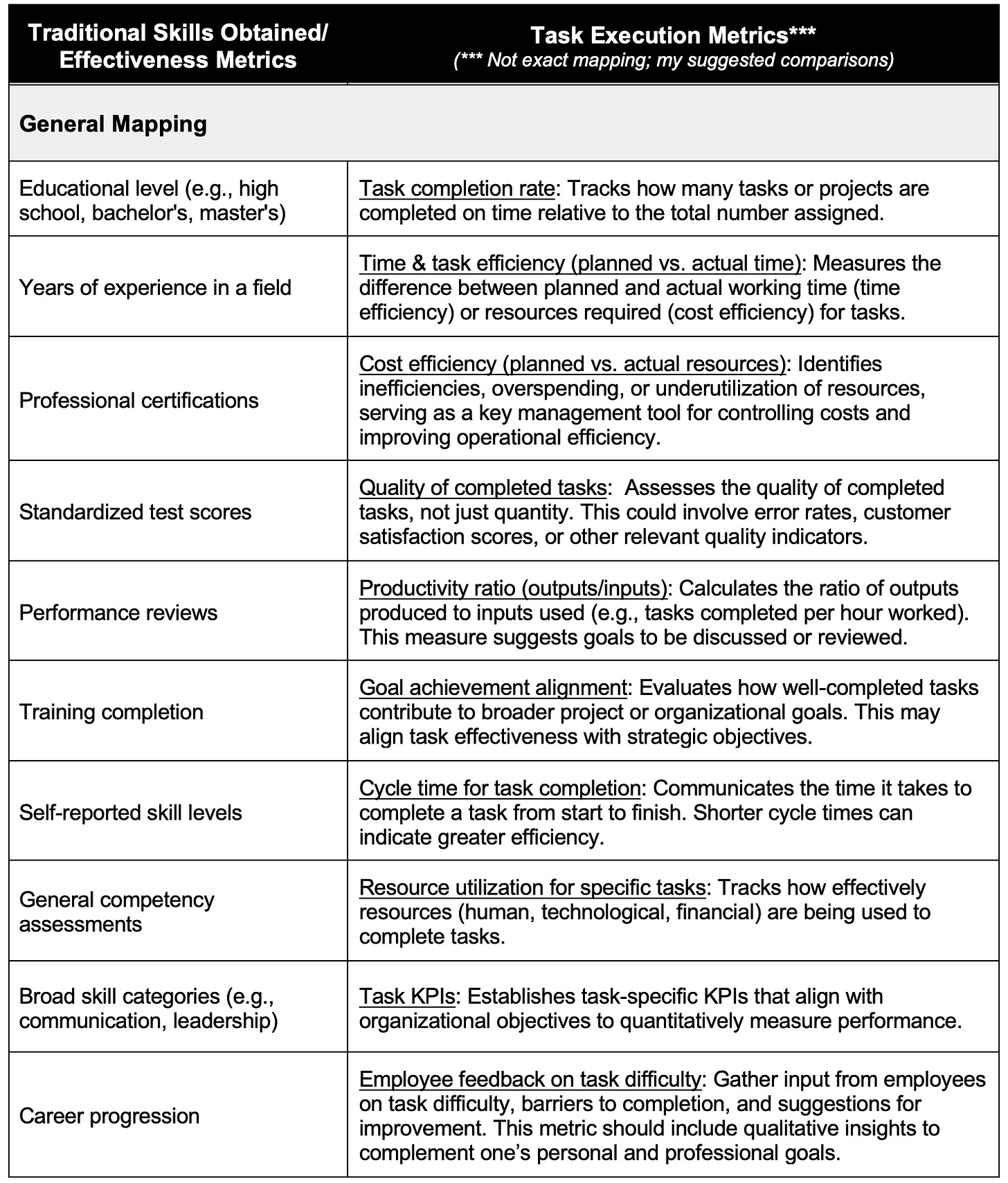

When considering a more quantifiable approach to measuring learning and performance, we need to recognize that many traditional methods in L&D may be critiqued or, at a minimum, compared and challenged. There are many traditional frameworks to compare, including Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels and related Phillips ROI Methodology, Brinkerhoff’s Success Case Method, Mager and Pipe’s Model for performance analysis, and many more. (See Appendix F)

How I’d summarize these comparisons and differences:

The attainment of skill proficiency differs versus successful task outcomes

Quality of skill application differs versus quality of task execution

Speed of skill deployment or time-to-productivity compared with task cycle or task completion duration

Skill error tolerance versus task error rates

Skill resourcefulness compared with resource utilization, and…

Perceived, subjective value of skills versus unambiguous, objective value of tasks

This section’s quantifiable, qualitative, and measurement considerations:

When designing your training program, if leaning towards a task-centric design, start with specific, measurable work outputs and focus goals on ‘what needs to be done’ versus ‘what needs to be known.’

From a measurement standpoint, you may need more metrics emphasis around faster time-to-productivity, closer alignment to existing performance or productivity metrics, time-to-application after the course has been completed, and Scrap Learning measurement, or validating the percentage of learning content that is immediately applicable to one’s job, versus the percentage of content not applied; i.e., “scrap”.

Get alignment and, ideally, support from your Operations and Manufacturing teams and any others who track task-performance–particularly where compliance and regulatory tracking are required. No one wants to mess with the data (or lack of) that could put you out of business.

From a positioning or messaging perspective, it may be confusing for the folks you’re trying to influence to tell a ‘skills-first story’ with a ‘task-centric story.’ Settle for the one that best aligns with the most common understanding and the one most aligned with C-level and Talent Management goals, which is probably your Skills-First story.

Measuring quantitative impact is not the be-all and end-all. Skill mastery and its application to work or a goal requires a comprehensive understanding of human behavior, motivations, and attitude, as well as execution and outcome.

4. SIMILARLY, TASKS FUEL LARGE LANGUAGE MODELS (LLMs) AND EVER-EVOLVING AI AGENTS

AI-Based technologies and LLMs like Gemini, Perplexity, or ChatGPT provide the most effective responses based on inputs that are ideally unambiguous, with a clear beginning and end. This predictability means LLMs thrive on clear requests or prompts, where resulting tasks can be grouped and standardized across different scenarios and contexts, such as data analysis for accountants reviewing terms and conditions and data analysis for marketers doing consumer trend analysis.

In contrast, as shared, skills are more abstract and influenced by varied definitions and uses, making them harder to classify uniformly. This results in LLM inaccuracies and hallucinations.

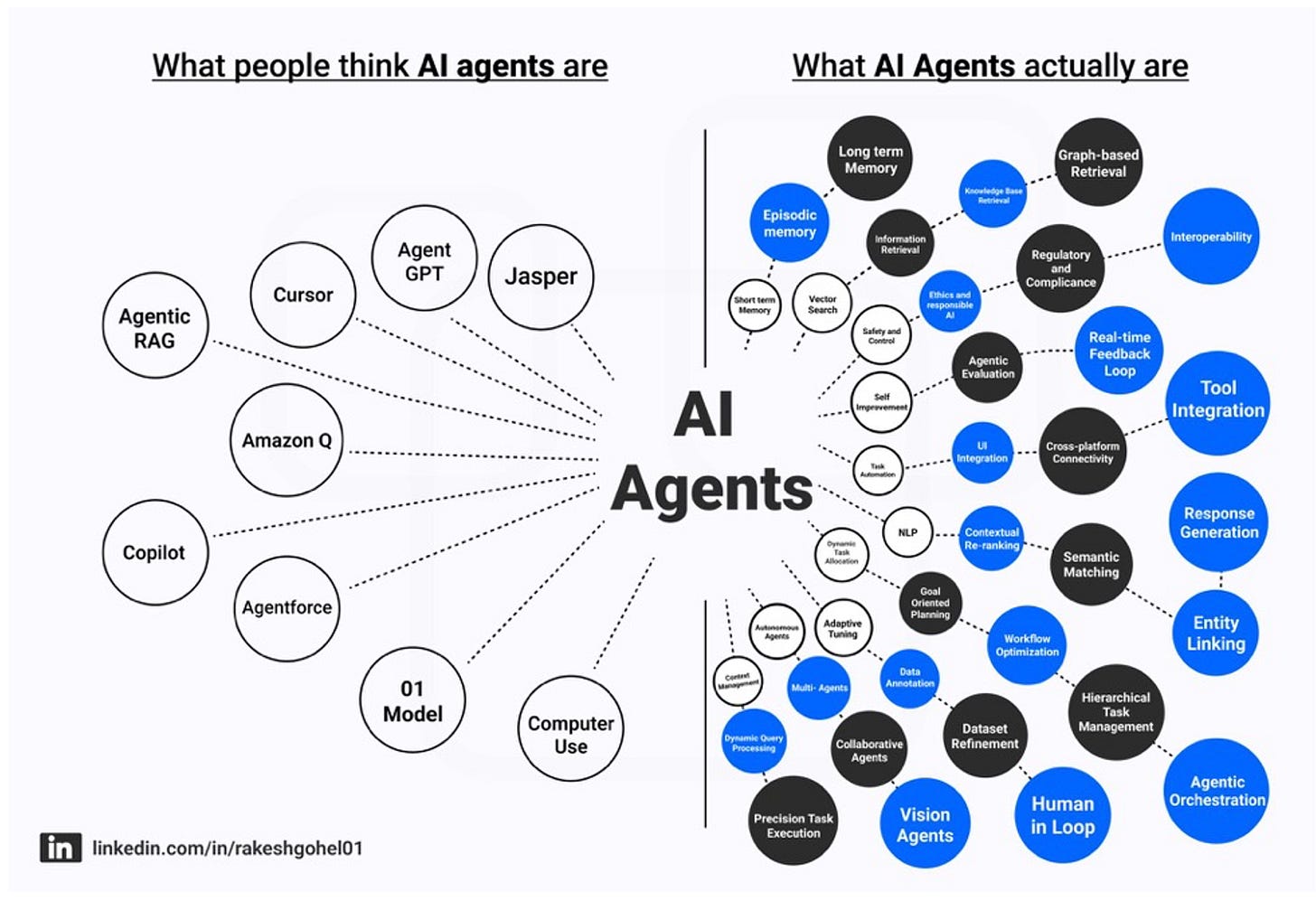

I tend to think about traditional large language models as the field-of play for experiencing AI, a space with certain guidelines, rules, and ‘pre-trained’ guidance. To push the metaphor a bit, who are the players on the field? That is, there are Human ones, and Agentic ones as teammates.

And the playing field, players and game are evolving so quickly.

For example, AI agents are not as narrow thinking when compared with a typical chatbot that answers basic queries and typically resides in the bottom right corner of a site, system, or application. These newer agents, representing the growing field of Agentic AI, can work independently, way beyond chatbots’ pre-defined rules or canned responses. They can do more challenging work For you, and in diverse ways.

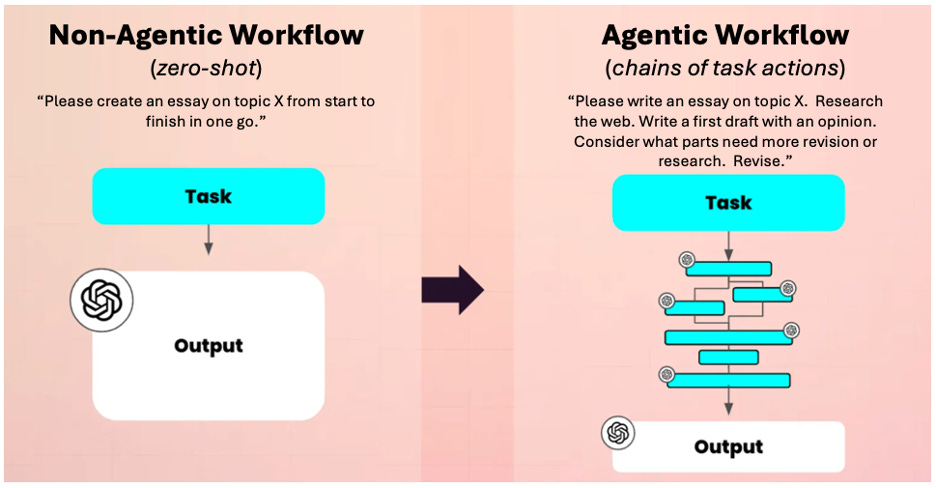

Another way to consider these differences is to compare how we ask Claude or Perplexity a single question or series of individual, disconnected questions. This is called ‘zero-shot’ prompting, where the prompt does not contain examples or what-if scenarios, resulting in a response solely based on the LLM’s pre-existing or pre-training data.

Imagine someone asking you to complete a task or set of steps that are new to you, yet there are no specific instructions or examples to follow. You can only rely on prior knowledge or something you’ve had to figure out independently. In general, this is how LLMs respond to zero-shot requests. While zero-shot can be very reliable and prone to more accurate responses, they are essentially generalization engines that may be accurate yet missing nuances and broader context. However, an agentic workflow is inherently revising, and revising, and revising to provide a more specific, detailed and ideally accurate response.

(Image by Alex Klein, The agentic era of UX)

What does this have to do with tasks? Regardless of one-way zero-shots or chains of tasks, tasks are discreet and defined with an intentional purpose and result, they are far more fluid, adaptable, and portable across diverse platforms and relatable scenarios.

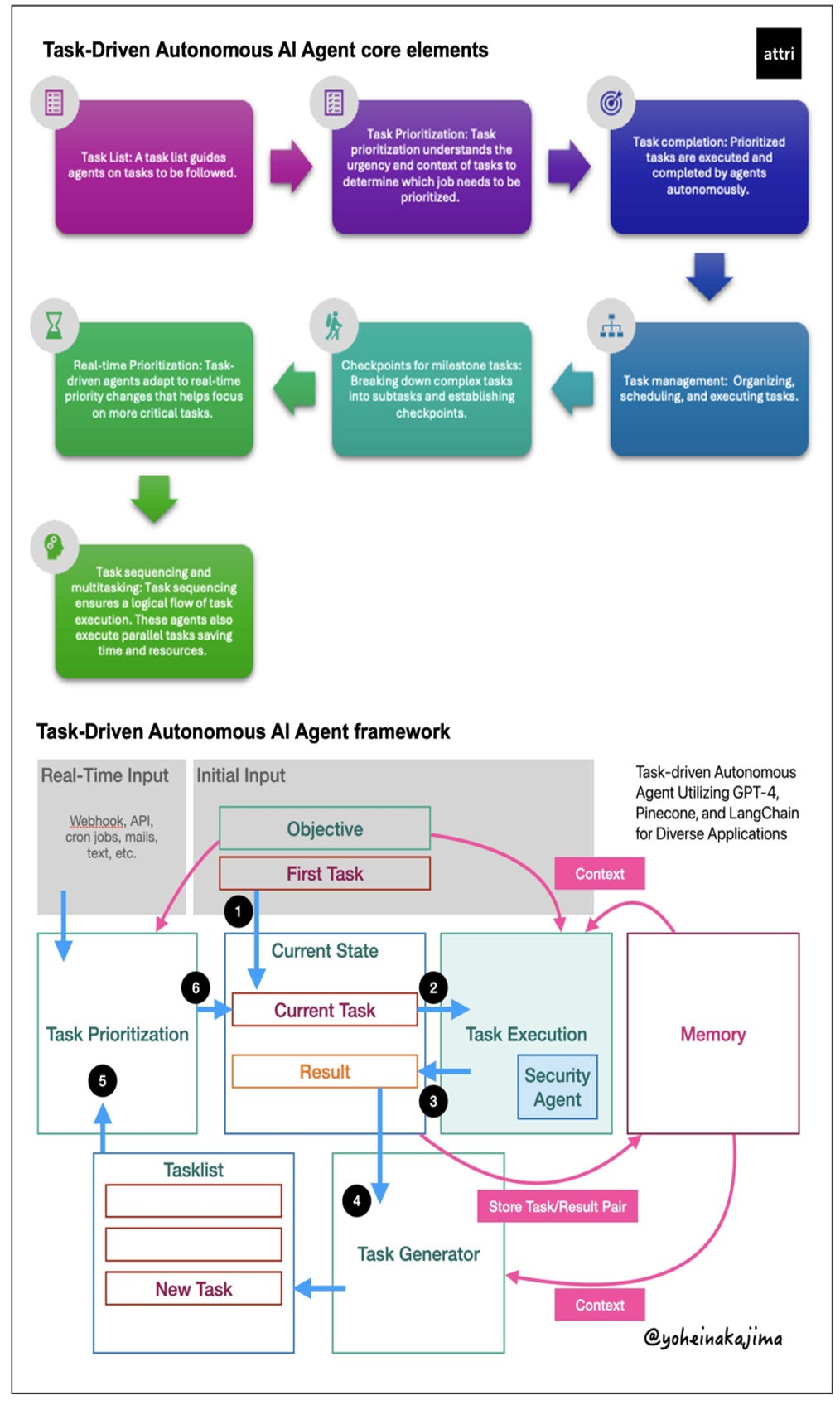

For example, companies like attri.ai are defining next-gen task-driven autonomous agents that excel across different systems, can make their own decisions, and learn along the way. (See Appendix G)

In general, “A task-driven autonomous AI agent is an AI agent that operates independently to perform specific tasks or achieve defined goals, adapt to or set priorities, learn from previous actions, and execute tasks without constant human intervention. These agents are designed to perceive their environment, make decisions, and take action based on their programmed objectives and the data they gather.”

Recognizing this may be a new and foreign approach to your teams and company, here are my forward-looking perspectives to keep in mind and ideally monitor:

Why Task-Driven AI Agents Matter

Boost productivity and engagement: Task-driven AI agents handle repetitive and routine tasks effectively, allowing employees to focus on more complex, creative, and rewarding work. This shift not only elevates productivity but also leads to higher employee engagement and satisfaction—no doubt a key driver of talent retention.

Increase training efficiency and cost savings: By deploying AI agents for specialized tasks, organizations can reduce costs associated with training and onboarding for certain repetitive roles. Task-driven agents can also scale as demand grows, reducing resource strain without adding training or infrastructure costs.

Reliability and accuracy: Task-focused AI agents are precise and reliable in their designated specializations, reducing errors and ensuring consistency—crucial for industries with high-stakes work like healthcare, finance, and customer service.

Enhancing decision-making and needs/task analysis: These agents can rapidly process and analyze large data sets, providing more effective decision-making. For L&D and employee experience programs, this can translate to a better understanding of employee behavior, performance trends, and learning preferences—enabling more personalized and impactful development strategies.

Simplified implementation: Unlike generalized AI systems requiring millions-to-billions of hardware and software ramp-up, task-driven AI agents do specialized work, and are easier to develop, deploy, and update as business needs change. Their adaptability ensures ongoing alignment with evolving organizational goals, helping learning teams stay agile in response to business shifts.

Reduce risk and ensure controls: Task-focused AI reduces the risk of unintended actions or decisions, which is especially important in critical or regulated environments. L&D professionals can rely on task-driven AI agents to safely support training and operational tasks, maintaining control and compliance.

Scale with flexibility: As organizations grow, task-driven AI agents can handle increased workloads without significant scaling costs, making them a sustainable choice. In the near future, L&D can focus resources on scaling development programs and supporting core competencies without being stretched thin by operational needs.

Playbook considerations:

Start experimenting with the growing list of platforms and tools allowing you to create your own AI agent. This currently includes Dialogflow (by Google Cloud), Kore.ai, Kumo.ai, ChatBot.com, Zapier Central, AgentGPT, Microsoft Azure Cognitive Services, and many others specializing in ‘no code’ ease for non-techies. [Our What-If #4 in this write-up is an experiment I made with OpenAI’s API model. Check it out at the end.]

Review areas within your current learning design processes that could be enhanced with AI agents. Many teams for example continue to leverage the ADDIE (analyze, design, develop, implement, evaluate) model when crafting their solutions. Identify common steps within the Analyze phase that could be conducted by or with agents. Scanning and reviewing strategic business assets (slides, business cases…) is a fairly straight-forward set of tasks that can give you a head start to align learning goals with company objectives. This includes providing design summaries to time-challenged subject-matter-experts (SMEs) to critique and approve versus conducting interviews, documentation reviews, approvals, etc.

Get better at prompting. Without good prompting, you may fall into a classic garbage-in, hallucinations-out dilemma, regardless of whether you’re working with zero-shots or testy AI Agentic colleagues. As of this writing, there are many free lessons too with OpenAI, Maximilian Vogel’s The Art of the Prompt course, Learn Prompting’s free courses, Vanderbilt University’s Prompt Engineering for ChatGPT, DeepLearning.AI, DALL-E 2’s Prompt Book, and lots more.

5. REVISIT YOUR APPROACH FOR ‘PERFORMANCE’ AND HOW HUMANS AND AGENTS WILL PERFORM TOGETHER

Tasks serve as a fundamental basis for evaluating overall job performance due to their measurable and directly observable nature. They can be linked to specific outcomes and outputs, making them valuable productivity and efficiency indicators. This approach to performance measurement also allows for more objective and standardized evaluations across different roles and organizational levels.

In this regard, performance can often be quantified in terms of speed, accuracy, or output, providing concrete metrics for comparison and improvement. As shared in “Toward an integrated model of work experience”, "Quantitative measures like the number of times a task has been performed, or time-based measures provide straightforward and valuable insights into performance outcomes."[22]

Studies also find that task-specific experience is a stronger predictor of performance than broad measures like job tenure. This foundation of task-based performance measurement aligns well with modern management practices that emphasize data-driven decision-making and continuous improvement. However, it's important to note that while tasks provide a solid foundation for performance measurement, they should be complemented with organizational and competence-based assessments.

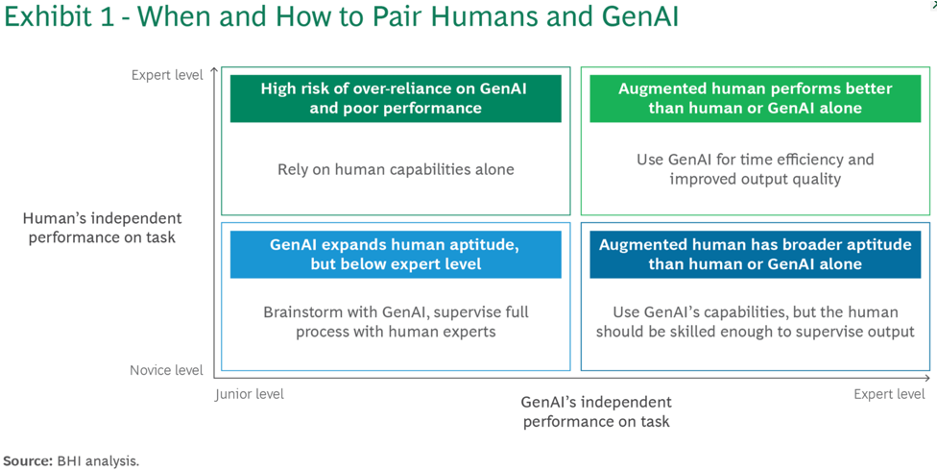

Yet, where do human folks like you and I partner, buddy up, or collaborate with AI agents? Who should be doing what based on task needs or requirements? Here is a handy two-by-two guide from BCG’s “GenAI Doesn’t Just Increase Productivity. It Expands Capabilities” suggesting where we should both work and perform together, or individually. [23]

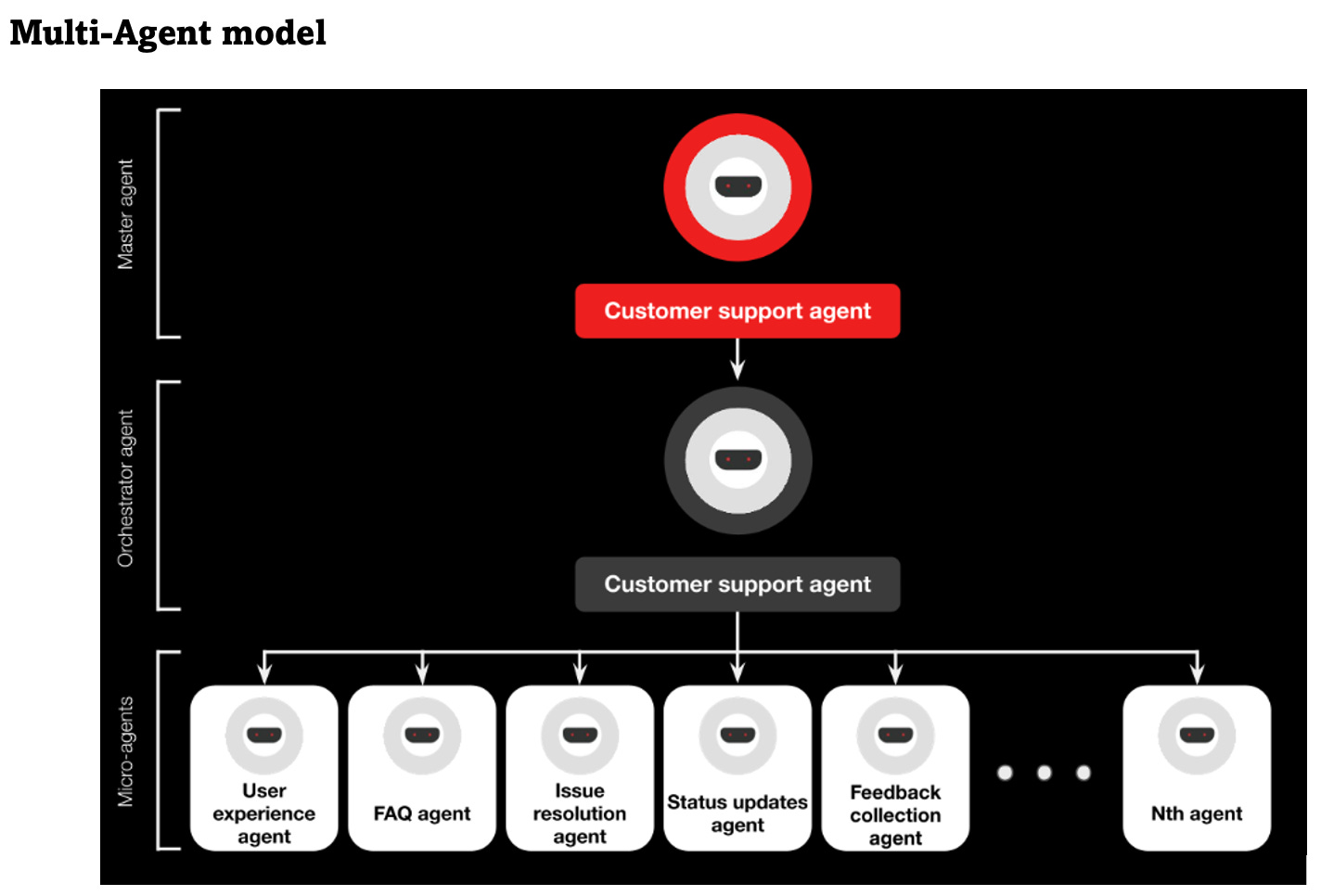

The pairing of humans and agents will not be exclusive to one agent working with one human worker or one team. When we consider more complex workflows requiring many options and decisions, or where multiple inputs, such as diverse databases or systems must be accessed, AI agents will work as teams of multi-agents to manage resource-heavy tasks. Their approach involves breaking down complex processes into smaller components, then working through each piece using targeted instructions.

(PWC Agentic AI - the new frontier in GenAI)

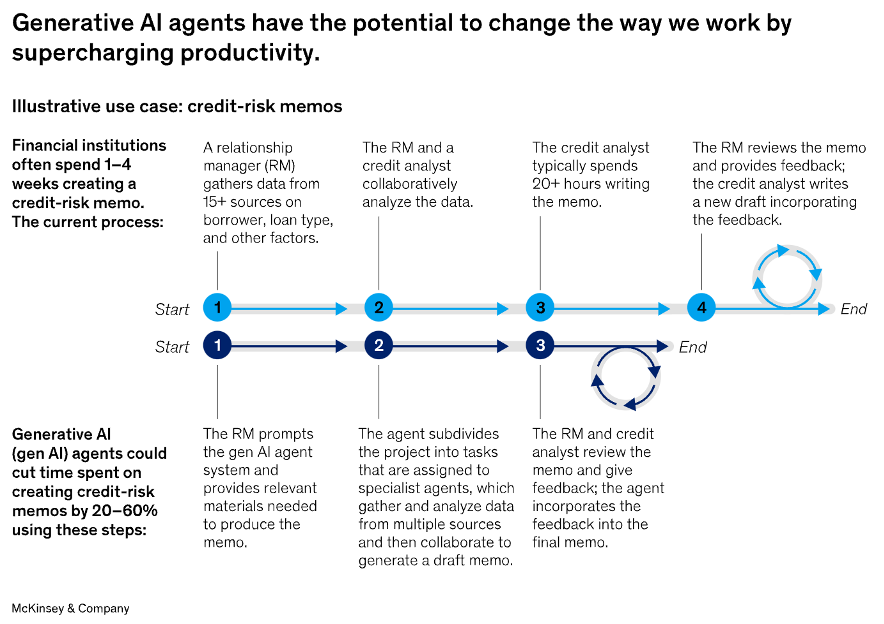

McKinsey’s report on “Why agents are the next frontier of generative AI” highlights a loan underwriting case study where “An agentic system—comprising multiple agents, each assuming a specialized, task-based role—could potentially be designed to handle a wide range of credit-risk scenarios. A human user would initiate the process by using natural language to provide a high-level work plan of tasks with specific rules, standards, and conditions. Then this team of agents would break down the work into executable subtasks.” [24]

Unlike basic AI models, intelligent agents can generate superior content while working alongside human experts, cutting review cycles by 20-60 percent. These agents excel at navigating multiple systems and synthesizing data from diverse sources. Still, their real power comes from transparency in partnership with human workers. When paired with human expertise, agents can document their entire analytical process - from initial data gathering to final insights. This allows human professionals, like credit-risk analysts, to quickly verify the agent's work by examining the complete audit trail of tasks, sources, and reasoning. This human-in-the-loop approach ensures both efficiency and accuracy, combining the agent's processing power with human judgment and domain expertise.

Performance considerations:

Analyze how your company determines or validates ‘successful on-the-job performance’, which will vary industry-to-industry, job-to-job etc.

Related, identify which performance metrics are reviewed at the C-level and work backwards to your SBO’s success criteria and promote, promote, promote.

Audit your learning content to evaluate which assets (courses, programs, assessments…) align with your company’s performance criteria. If you need help, companies like Retrain.AI, Reejig, and Filtered excel in this.

Lastly, when considering the impacts of GenAI on job performance, stay close to where “tasks” play best when pairing workers with GenAI tools or approaches. We should not assume that GenAI has or will provide broad capability support, particularly at the task-level. Worse, workers may rely too much on GenAI and agents to fulfill comprehensive support or duties.

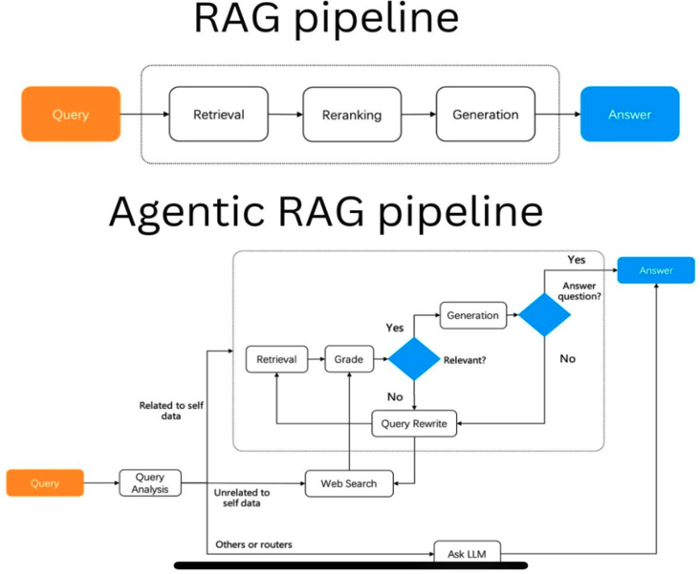

6. ROUTINE TASKS ARE THE FOUNDATION FOR AUTOMATION, PROMPTING, AND RETRIEVAL-AUGMENTED GENERATION (RAG)

Tasks, particularly routine ones, are ideal for automation because they are structured and standardized, making them easier to translate into algorithms or integrate with AI systems. As Fernández-Macías & Bisello explain "Routine tasks, as opposed to non-routine, are technically easier to codify and automate; these can be either cognitive (such as record keeping) or manual (such as repetitive assembly)." This process allows tasks to be broken down into smaller components, which can be efficiently automated, outsourced, or assigned to human talent. [25]

The idea of routinization helps explain why repetitive tasks are more likely to be automated. Here, routine tasks are defined as “those that require methodical repetition of an unwavering procedure” and “sufficiently well understood [tasks] that can be fully specified as a series of instructions to be executed by a machine.” Ohly, Göritz, and Schmitt’s research “The power of routinized task behavior for energy at work” continues that the more repeatable a task may be, the greater probability that it can be successfully automated and removed from the drudgery of mundane work.

Task-based entries are also more portable and can be effectively integrated into models like Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). RAG techniques leverage both parametric and non-parametric memory to access information and generate more accurate outputs. Parametric memory refers to the internal knowledge that the AI model has learned during training (e.g., OpenAI’s engineers training ChatGPT 4 on specific data). In contrast, non-parametric memory is external data that the model retrieves when generating answers (ChatGPT leveraging the Library of Congress).

Yet, as explained by Avishek Biswas in Toward Data Science, how is everyday LLM prompting different from RAG? “When providing accurate and up-to-date information is key, you cannot rely on the LLM’s inbuilt knowledge. RAGs are a cheap, practical way to use LLMs to generate content about recent topics or niche topics without needing to finetune them on your own and burn away your life’s savings.” Example:

As shared in “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks”, "Hybrid models that combine parametric memory with non-parametric memory can address issues like expanding knowledge and providing interpretability, which makes task-based inputs particularly suitable for these systems." This suggests that an RAG approach handling task-specific instructions--where the information needs to be both internally generated and externally retrieved--provides far more clarity with reduced errors and, ideally, fewer hallucinations. [26]

This section’s Routinization of tasks considerations:

Conduct a task audit experiment to identify, catalog, and prioritize routine tasks that can benefit from automation. Focus on repetitive, time-consuming, and low-value tasks, gathering team input for a comprehensive view. Related, test new templates for routine tasks that are friendly with your preferred or approved LLM.

Enable the team to learn automation methods by providing training and, ideally, industry contacts covering maintenance, troubleshooting, and productivity best practices. Zapier and Adobe have great case studies of embedding more automation into their L&D team’s processes and services.

Optimize prompt engineering techniques and build a library of grassroots-built and curated task-specific prompts from anyone designing, deploying, measuring, and managing your training programs. Great L&D experts to follow: Ross Stevenson’s Steal These Thoughts, Egle Vinauskaite and Donald H Taylor’s AI in L&D reports, Dr. Philippa Hardman’s DOMS Newsletter, Donald Clark’s Plan B, Katja Schipperheijn, and there are so many others.

Work with your IT or data architecture team to experiment with Retrieval-Augmented Generation approaches and test a segment of your content. Suggest technical content first, as it’s more binary and easier to add clear metadata or tagging. If you have existing Instructional Quality standards for content, reference these standards to train your RAG approach and ideally retrieve higher quality assets more efficiently. (See What-If #4 for more on Instructional Quality.)

As shared, if you want to learn Gen AI, you must use GenAI. Here is a great, recent list: Top 20 AI Tools for Boosting Learning & Development in 2024, The 5 Best AI Tools For L&D Teams in 2024, The Best AI Tools for Learning & Development.

7. TRADITIONAL TASK-ANALYSIS JUST GOT MORE HIP

First, some history… Task analysis in workforce development has evolved from its Industrial Revolution roots to become a sophisticated tool for improving workplace efficiency and training. Frederick Winslow Taylor's scientific management principles in the early 20th century formalized the process, which was further developed during World War II through the Training Within Industry (TWI) service. Post-war advancements led to more specialized approaches, including Job Task Analysis (JTA) and behavioral task analysis. JTA focuses on breaking down specific job roles into detailed tasks and subtasks, identifying the knowledge, skills, and abilities required for each.

AI is revolutionizing modern workforce development task analysis, making the process significantly more efficient, personalized, and dynamic. Perhaps a JTA-enabled approach could be used based on the following intriguing examples.

The first example highlights ‘automation improvement opportunities’ for white collar office workers via Task Mining, and the second is a bit more profound regarding deskless workers in the field, such as a construction site, and how Multimodal AI may put dynamic task analysis on an entirely new level.

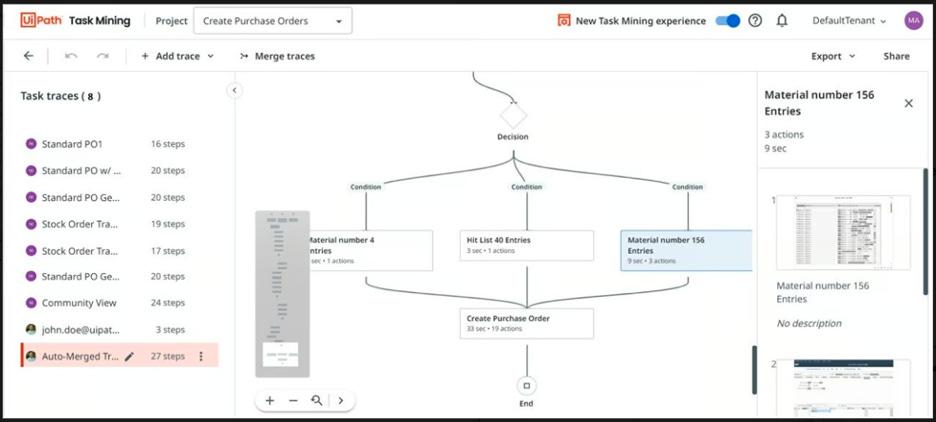

Task Mining with Process Discovery Tools

Here, AI analyzes your desktop activities to identify and rank the best automation and process tasks and opportunities. Companies like UiPath capture your desktop tasks and activities without interrupting your work, collect detailed metrics, and provide analytics. Moreover, UiPath’s agents will streamline inefficient workflows and consistently monitor human and human + agent augmented work.

(Image: UiPath)

What this means is previously (oh, say, 2019), someone trying to identify a hiccup within the flow of daily computer work would typically need to monitor you ‘over-the-shoulder’ to confirm, itemize and document each task or step. No more (!!), and just think about the documentation, validation, accuracy and operational efficiencies gains.

Multimodal AI for task analysis is here. It ain’t perfect, but neither are we.

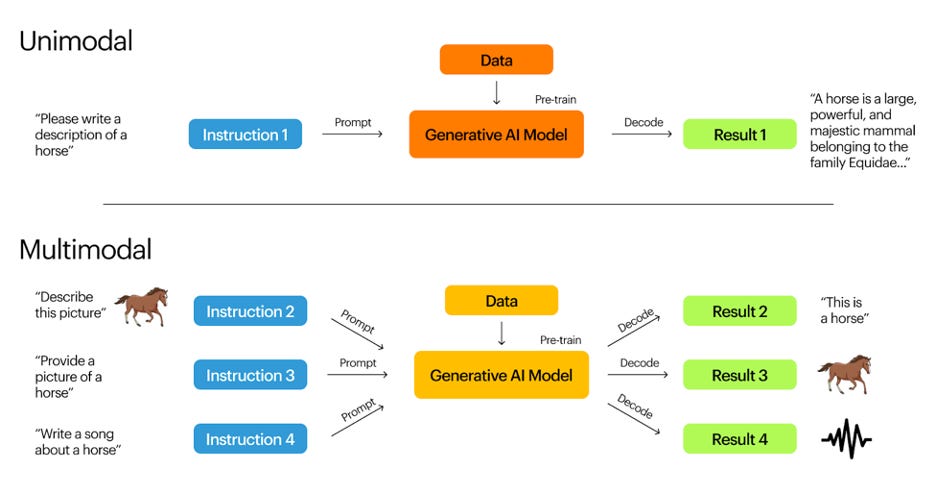

Multimodal AI refers to an AI model that can intake any source like spreadsheets, videos, images, text, and audio, do the processing required, and feed you back similar, diverse analyses and assets. This is an example of what a multimodal AI process can look like via an old school ‘unimodal’ and new school ‘multimodal’:

(Image: https://www.researchgate.net/)

Rather than the most popular, current approach where a user request or prompt is interpreted and processed by one primary GenAI model like a Perplexity or Claude LLM, multimodal can do similar interpretation and processing, yet from many sources. This can include both inbound sources of text, code, visuals, and audio and output or decode with similar variations.

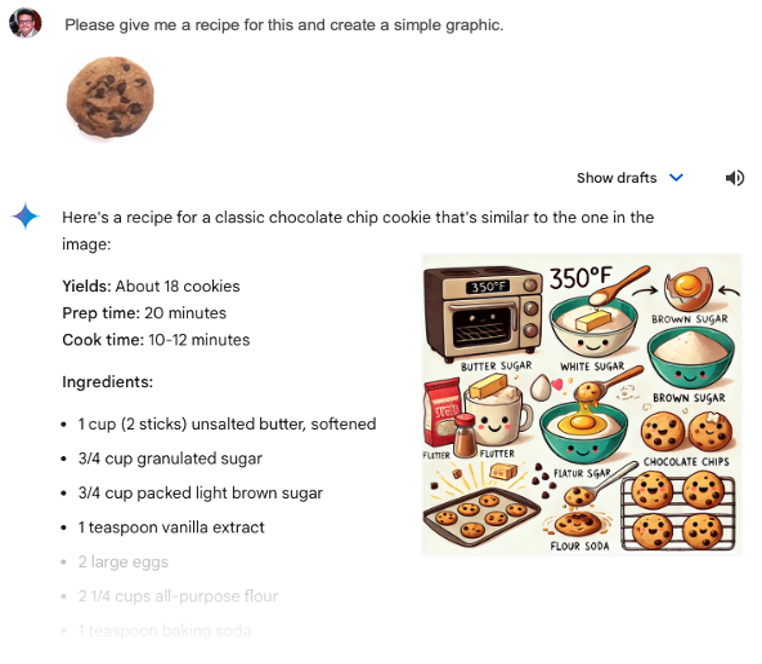

Here are a couple specific examples. The first leverages Google’s multimodal model Gemini LLM to help us a) interpret a single photo, b) explore the internet for its ‘meaning,’ and c) respond to the prompt to build a recipe representing the image and create a simple graphic. Notice that no image description is provided, so Gemini must use ‘reasoning’ skills and provide three different outputs: text, a structured set of steps, and a visual representation. Additionally, Gemini’s multimodal visual interpreted the intention of the prompt to be related to a primary ‘user’ of chocolate chip cookies, or in this case… for kids, thus a bit of nostalgic artistry.

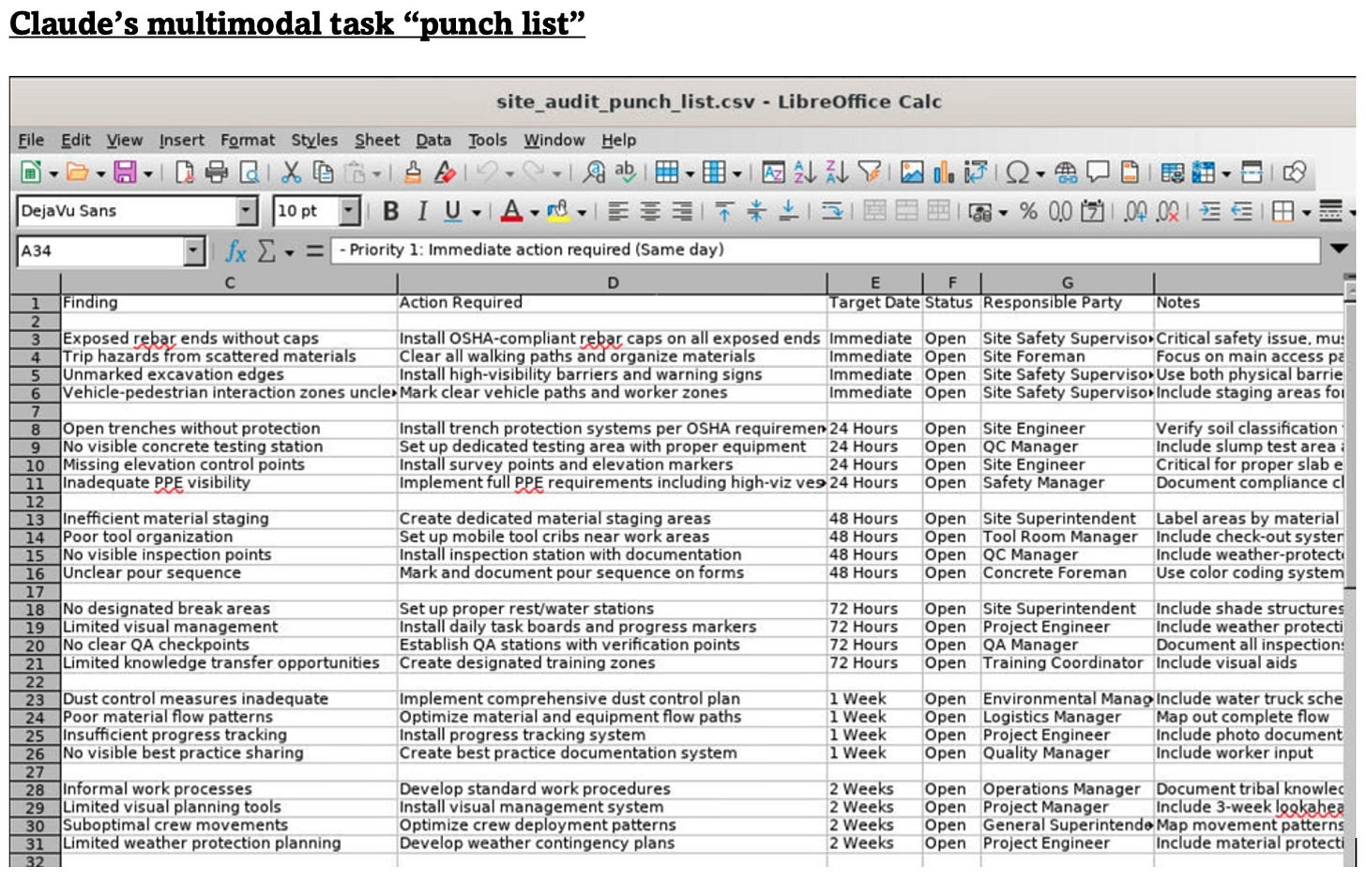

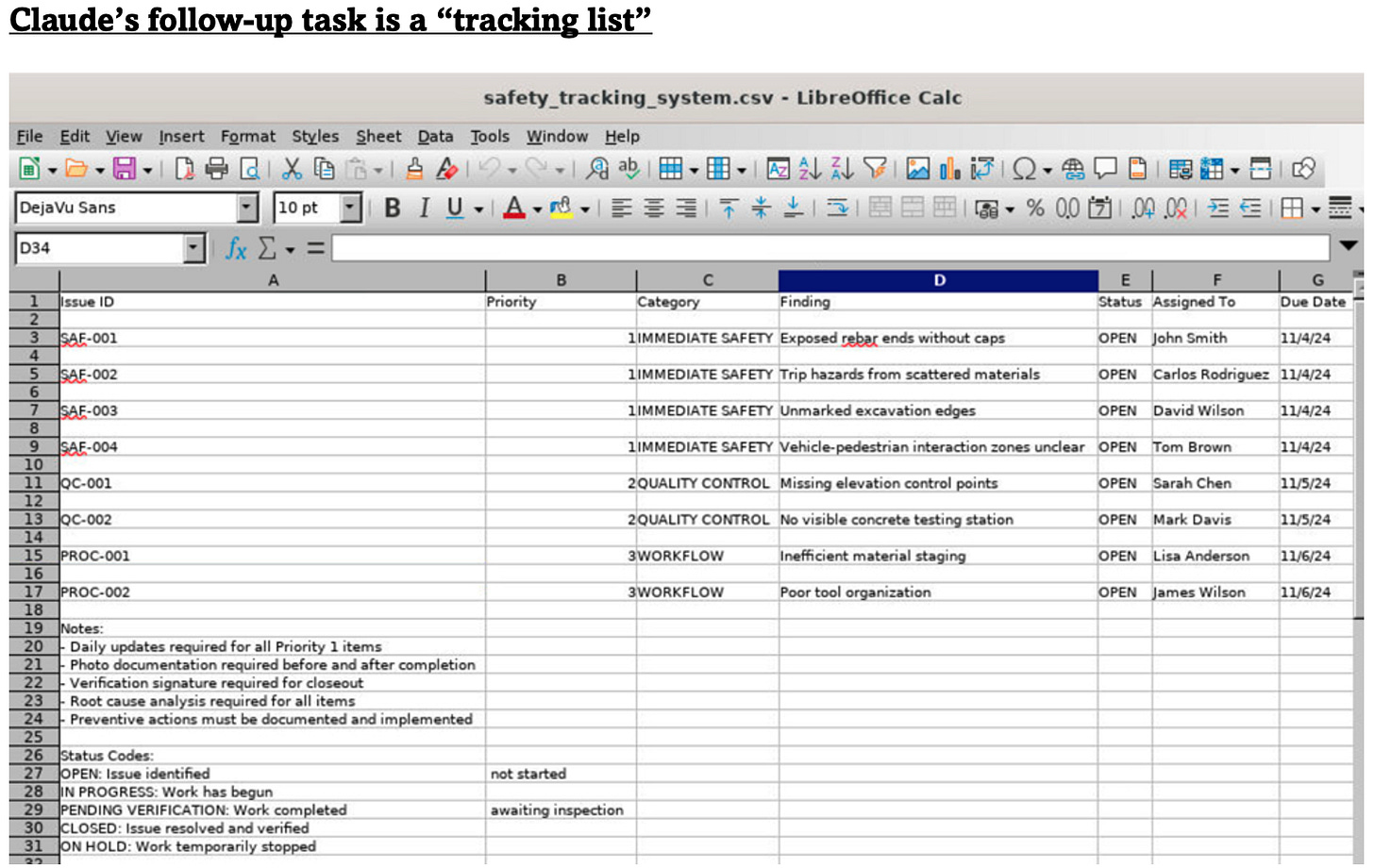

In this second, far more robust example, AI guru Ethan Mollick uses Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet to analyze a YouTube video from a construction site, asks Sonnet to process the images, interpret what it sees, and identify scenarios and task-based solutions to address potential work safety concerns. “I gave Claude a YouTube video of a construction site and prompted: “You can see a video of a construction site; please monitor the site and look for issues with safety, things that could be improved, and opportunities for coaching.” There is no special training here, just the native ability of Claude 3.5 Sonnet… analyzes various aspects of the construction site: workers' protective equipment usage, placement of materials, work patterns, and potential hazards - making a note of each.”

(Full video and article here)

This multimodal analysis is just one part of this multimodal example. After the next prompt, “What did you conclude? Write up your observations as a punch list,” Claude Sonnet created two spreadsheets. One is identifying several safety issues, “reasoning” their importance, and summarizing a recommendation of task actions. Then Claude asked Ethan, “Would you like to create a tracking system for completion verification?” The results:

Final considerations:

Refresh and stay current on proven, established, and classic task analysis approaches. While AI advances with more real-world applications, the methods or rubrics of choice remain extremely valid. Examples: Skill Decomposition, Hierarchical Task Analysis (HTA), and Cognitive Task Analysis (CTA).

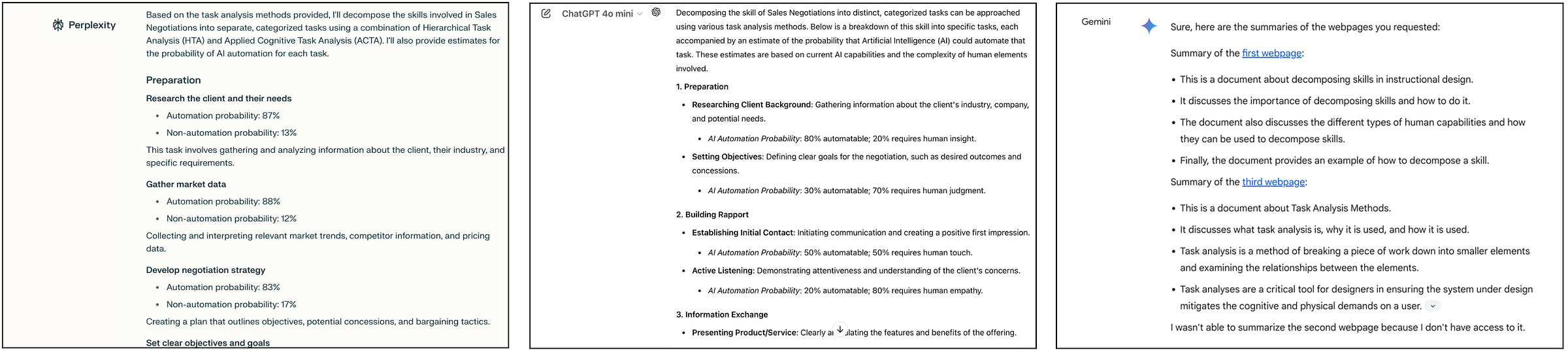

Related, ask your favorite LLM to a) “Using these three XYZ workflow procedures…” b) identify the skills required to conduct XYZ and c) break down each skill into task-level components.” While it may not be exact, it’s a good experiment to use with different LLM models or approaches. Here’s my take or experiment using three different LLMs to improve my sales negotiation skills. Note: I also added a ‘probability percentage’ to the prompt to indicate whether that task was automated. Here’s Perplexity’s. Here’s ChatGPT 4o. And here’s Gemini’s.

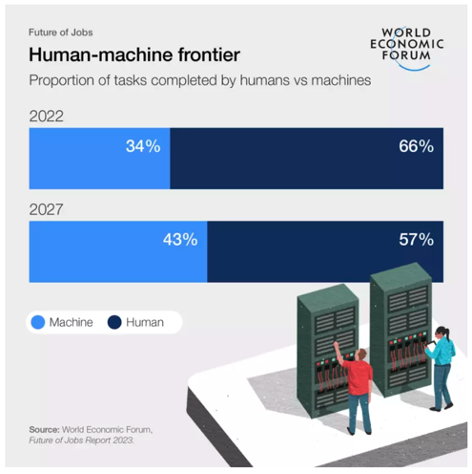

Also related, the analysis and frameworks above highlight that AI has the potential–and is already affecting–many existing and future roles. In both scenarios, remember the percentage of a job’s tasks being impacted versus the full job or full set of skills when conducting your task analysis. Especially for white-collar jobs that are more affected by automation, in most cases, the abundance of change is again at the task level, i.e., the percentage of activities, actions, or tasks that may be replaced versus the percentage of skills. The WEF Future of Jobs site is a good source to follow. A related, recent example:

Finally, review current frameworks and lists where a skill may already be broken down or decomposed for you, encouraging a more standardized and scalable approach. Examples: Skills Builder Universal Framework (not overly comprehensive, but scalable given its simplicity), O*NET OnLine - Example Computer Programmers (this is more work or job occupation structure, and very rich), and LightCast’s Open Skills Library.

Links: Part 1: Introduction, Part 2: Playbook, Part 3: Let Learning Breathe, Part 4: Task Intelligence Control Room, Part 5: Tasks as EX Product, Part 6: IQA Prototype, Part 7: Talent Is Not a Commodity; Google Books “Tasks vs Skills” free ebook (Parts 1-6 only).

Special thanks to colleagues who guided me as contributors and reviewers, and to so many who have inspired my thinking and curiosity on this subject.

Contributors: Cathy Moore, Clark Quinn, Felipe Hessel, Gianni Giacomelli, Giri Coneti, Jon Fletcher, Julie Dirksen, Megan Torrance, Nick Shackleton-Jones, Nina Bressler, Will Thalheimer, Ross Dawson

Inspirations: Allie K. Miller, Amanda Nolen, Andrew Kable (MAHRI), Bhaskar Deka, Brandon Carson, Brian Murphy, Chara Balasubrmanian, Dani Johnson, Darren Galvin, Dave Buglass Chartered FCIPD, MBA, Dave Ulrich, David Green 🇺🇦, David Wilson, Deborah Quazzo, Dennis Yang, Detlef Hold, Donald Clark, Donald H Taylor, Dr Markus Bernhardt, Dushyant Pandey, Egle Vinauskaite, Emma Mercer (Assoc CIPD, MLPI), Ethan Mollick, Gordon Trujillo, Guy Dickinson, Harish Pillay, Hitesh Dholakia, Isabelle Bichler-Eliasaf, Isabelle Hau, Joel Hellermark, Joel Podolny, Johann Laville, Jon Lexa, Josh Bersin, Josh Cavalier, Joshua Wöhle, Julian Stodd, Karen Clay, Karie Willyerd, Kate Graham, Kathi Enderes, Marga Biller, Marc Zao-Sanders, Meredith Wellard, Mikaël Wornoo🐺, Nico Orie, Noah G. Rabinowitz, Nuno Gonçalves, Oliver Hauser, Orsolya Hein, Patrick Hull, Peter Meerman, Peter Sheppard, Dr Philippa Hardman, Raffaella Sadun, Ravin Jesuthasan, CFA, FRSA, René Gessenich, Ross Dawson, Ross Garner, Sandra Loughlin, PhD, Simon Brown, Stacia Sherman Garr, Stefaan van Hooydonk, Stella Collins, Trish Uhl, PMP 👋🏻, Tony Seale, Zara Zaman

Acknowledging leveraging Perplexity, Gemini, ChatGPT, and Claude for research, formatting, testing links, challenging assumptions and aiding the creative process.

LICENSING

Unless otherwise noted, the contents of this series are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Should you choose to exercise any of the 5R permissions granted you under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license, please attribute me in accordance with CC's best practices for attribution.

If you would like to attribute me differently or use my work under different terms, contact me at https://www.linkedin.com/in/marcsramos/.

APPENDICES

Appendix C

For a more current view of diverse skills taxonomies, I chose five catalogs below that vary in application, how they’re structured, and related criteria such as key similarities and differences, task-centricity, and from an AI perspective.

Table 3: Skills taxonomy comparisons (not exhaustive)

Appendix D

Table 4: Summarizing comparative examples: Taxonomy, Ontology, and Frameworks

Appendix E

Table 5: A proposal for a comprehensive taxonomy of tasks

Appendix F

Exploring the Kirkpatrick approach, we gain a clearer representation of a current foundational measurement approach, which is a bit more focused on obtaining a skill (and other factors), with a comparison of a task-centric set of measurements.

Table 5: Traditional skill and task-centric measurements

Appendix G

An example of attri.ai references related to a task-first approach contains these core elements or steps:

Graphic 6: Task-driven autonomous agents

https://x.com/yoheinakajima/status/1640934501198213120

NOTES

Seven playbook takeaways on how to win with AI, tasks, and skills

[19] a more modern hierarchical classification: Fernández-Macías, E., Bisello, M. , (2024), “A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Tasks for Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on Work”, Soc Indic Res 159, 821–841 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02768-7

[20] measurement priority should lean towards: Tesluk, P. E., & Jacobs, R. R. (1998). Toward an integrated model of work experience. Personnel Psychology, 51(2), 321–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00728.x

[21] measurable productivity gains from breaking down tasks: Enrique Fernández-Macías & Martina Bisello, (2022), "A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Tasks for Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on Work," Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement, Springer, vol. 159(2), pages 821-841, January.

[22] time-based measures provide straightforward and valuable insights: Tesluk, P. E., & Jacobs, R. R., (1998), “Toward an integrated model of work experience”, Personnel Psychology, 51(2), 321–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1998.tb00728.x

[23] Here is a handy two-by-two guide: Daniel Sack, Lisa Krayer, Emma Wiles, Mohamed Abbadi, Urvi Awasthi, Ryan Kennedy, Cristián Arnolds, and François Candelon, (2024), “GenAI Doesn’t Just Increase Productivity. It Expands Capabilities.”, BCG Publications, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2024/gen-ai-increases-productivity-and-expands-capabilities

[24] agents would break down the work: Lareina Yee, Michael Chui, Roger Roberts, Stephen Xu, (2024), “Why agents are the next frontier of generative AI”, McKinsey Quarterly, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/why-agents-are-the-next-frontier-of-generative-ai#/

[25] Routine tasks, as opposed to non-routine: Fernández-Macías, E., Bisello, M. A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Tasks for Assessing the Impact of New Technologies on Work. Soc Indic Res 159, 821–841 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02768-7

[26] reduced errors and, ideally, fewer hallucinations: Patrick Lewis, Ethan Perez, Aleksandra Piktus, Fabio Petroni, Vladimir Karpukhin, Naman Goyal, Heinrich Küttler, Mike Lewis, Wen-tau Yih, Tim Rocktäschel, Sebastian Riedel, Douwe Kiela, (2021), “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks”, Facebook AI Research; University College London; New York University, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.11401

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES (ALL 7 PARTS OF THIS SERIES)

Wen, J., Zhong, R., Ke, P., Shao, Z., Wang, H., & Huang, M., (2024), “Learning task decomposition to assist humans in competitive programming”, Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2024), https://arxiv.org/pdf/2406.04604

Wang, Z., Zhao, S., Wang, Y., Huang, H., Shi, J., Xie, S., Wang, Z., Zhang, Y., Li, H., & Yan, J., (2024), “Re-TASK: Revisiting LLM tasks from capability, skill, and knowledge perspectives”, arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.06904

Hubauer, T., Lamparter, S., Haase, P., & Herzig, D., (2018), “Use cases of the industrial knowledge graph at Siemens”, Proceedings of the International Workshop on the Semantic Web, CEUR Workshop Proceedings, https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2180/paper-86.pdf

Erik Brynjolfsson, Danielle Li, Lindsey R. Raymond, “Generative AI At Work”, http://www.nber.org/papers/w31161 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 April 2023, revised November 2023, https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31161/w31161.pdf

https://www.royermaddoxherronadvisors.com/blog/2016/april/the-knowledge-worker-in-healthcare/

Connie J.G Gersick, J.Richard Hackman, (1990), “Habitual routines in task-performing groups, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/074959789090047D

Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes”, Volume 47, https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(90)90047-D

World Economic Forum, (2023), “Future of Jobs Report 2023”, World Economic Forum, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf

Boston Consulting Group, (2024), “How people can create—and destroy—value with generative AI”, BCG, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/how-people-create-and-destroy-value-with-gen-ai

Kaisa Savola, (2024), Challenges Preventing Organizations from Adopting a Skills-Based Model”, LinkedIn, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/challenges-preventing-organizations-from-adopting-savola-she-her--24c6f/

Patel, A., Hofmarcher, M., Leoveanu-Condrei, C., Dinu, M.-C., Callison-Burch, C., & Hochreiter, S., (2024), “Large language models can self-improve at web agent tasks”, arXiv, https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.20309

Sagar Goel and Orsolya Kovács-Ondrejkovic, (2023), “Your Strategy Is Only as Good as Your Skills”, BCG Publications, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/your-strategy-is-only-as-good-as-your-skills

“Workplace 2.0: The Promise of the Skills-Based Organization”, (2024), Udemy Business, https://info.udemy.com/rs/273-CKQ-053/images/udemy-business-workplace-2.0-promise-skills-based-organization.pdf?version=0

Shakked Noy and Whitney Zhang (2023): “Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence”, MIT Economics Department working paper. Retrieved March 13, 2023 from https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Noy_Zhang_1_0.pdf

“AI at Work Is Here. Now Comes the Hard Part.”, (2024), 2024 Work Trend Index Annual Report from Microsoft and LinkedIn, https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/worklab/work-trend-index/ai-at-work-is-here-now-comes-the-hard-part

“LinkedIn Workplace Learning Report”, (2024), LinkedIn Learning, https://learning.linkedin.com/content/dam/me/business/en-us/amp/learning-solutions/images/wlr-2024/LinkedIn-Workplace-Learning-Report-2024.pdf

Macnamara BN, Berber I, Çavuşoğlu MC, Krupinski EA, Nallapareddy N, Nelson NE, Smith PJ, Wilson-Delfosse AL, Ray S. “Does using artificial intelligence assistance accelerate skill decay and hinder skill development without performers' awareness?”, Cogn Res Princ Implic. 2024 Jul 12;9(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s41235-024-00572-8. PMID: 38992285; PMCID: PMC11239631, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11239631/

Matt Beane, (2024), “The Skill Code: How to Save Human Ability in an Age of Intelligent Machine”, Harper, https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/how-can-we-preserve-human-ability-age-machines

Lazaric, N., (2012), “Routinization of Learning”, Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Springer, Boston, MA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_246

Hering, A., & Rojas, A., (2024), “AI at Work: Why GenAI Is More Likely To Support Workers Than Replace Them.”, Indeed Hiring Lab, https://www.hiringlab.org/2024/09/25/artificial-intelligence-skills-at-work/

Morgan, T. P., (2024), “How GenAI Will Impact Jobs In the Real World”, HPCwire, https://www.hpcwire.com/2024/09/30/how-genai-will-impact-jobs-in-the-real-world/

https://trainingindustry.com/magazine/fall-2022/improving-the-productivity-of-knowledge-workers/

Balasubramanian, R., Kochan, T. A., Levy, F., Manyika, J., & Reeves, M., (2023), “How People Can Create—and Destroy—Value with Generative AI”, Boston Consulting Group, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2023/how-people-create-and-destroy-value-with-gen-ai

Marcin Kapuściński, (2024), “Boosting productivity: Using AI to automate routine business tasks”, TTMS, https://ttms.com/boosting-productivity-using-ai-to-automate-routine-business-tasks/

https://scheibehenne.com/ScheibehenneGreifenederTodd2010.pdf

Paulo Carvalho, (2024), “How Generative AI Will Transform Strategic Foresight”, IF Insight & Foresight, https://www.ifforesight.com/post/how-generative-ai-will-transform-strategic-foresight

Deok-Hwa Kim, Gyeong-Moon Park, Yong-Ho Yoo, Si-Jung Ryu, In-Bae Jeong, Jong-Hwan Kim, (2017), “Realization of task intelligence for service robots in an unstructured environment”, Annual Reviews in Control, Volume 44, ISSN 1367-5788, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2017.09.013.

Kweilin Ellingrud, Saurabh Sanghvi, Gurneet Singh Dandona, Anu Madgavkar, Michael Chui, Olivia White, Paige Hasebe, (2023), “Generative AI and the future of work in America”, McKinsey Global Institute, https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/generative-ai-and-the-future-of-work-in-america#/

MIT Technology Review Insights, (2024), “Multimodal: AI’s new frontier”, https://wp.technologyreview.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Jina-AI-e-Brief-v4.pdf?utm_source=report_page&utm_medium=all_platforms&utm_campaign=insights_ebrief&utm_term=05.02.24&utm_content=insights.report

Sandra Ohly, Anja S. Göritz, Antje Schmitt, (2017), “The power of routinized task behavior for energy at work”, Journal of Vocational Behavior, Volume 103, Part B, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.08.008

Baddeley, A.D. (2003). Working memory: looking back and looking forward. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4, p.829-839, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14523382/

Baddeley, A.D. and Hitch, G. (1974). Working Memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 8, p.47-89, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982209021332

Chandler, P. and Sweller, J. (1991). Cognitive Load Theory and the Format of Instruction. Cognition and Instruction, 8 (4), p. 293-332, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s1532690xci0804_2

Chandler, P. and Sweller, J. (1992). The split-attention effect as a factor in the design of instruction. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 62 (2), p.233–246, https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1992.tb01017.x

Clark, R.C., Nguyen, F. and Sweller, J. (2006). Efficiency in learning: evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. San Francisco: Pfeiffer, https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1992.tb01017.x

Marzano, R.J., Gaddy, B.B. and Dean, C. (2000). What works in classroom instruction. Aurora, CO: Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning, https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1992.tb01017.x

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive Load during Problem Solving: Effects on Learning. Cognitive Science, 12, p.257-285, https://mrbartonmaths.com/resourcesnew/8.%20Research/Explicit%20Instruction/Cognitive%20Load%20during%20problem%20solving.pdf

Wenger, S.K., Thompson, P. and Bartling, C.A. (1980). Recall facilitates subsequent recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6 (2), p.135-144, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x?journalCode=ppsa

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00012.x?journalCode=ppsa

Choi, S., Yuen, H. M., Annan, R., Monroy-Valle, M., Pickup, T., Aduku, N. E. L. & Ashworth, A. (2020). Improved care and survival in severe malnutrition through eLearning. Archives of disease in childhood, 105(1), 32-39. Doi:10.1136, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31362946/

Chyung, Y. C. (2007). Learning object-based e-learning: content design, methods, and tools. Learning Solutions e-Magazine, August 27, 2007, 1-9. https://www.elearningguild.com/pdf/2/082707des-temp.pdf.

https://dobusyright.com/druckers-six-ideas-about-knowledge-work-environments-dbr-031/

Doolani, S., Owens, L., Wessels, C. & Makedon, F. (2020). vis: An immersive virtual storytelling system for vocational training. Applied Sciences, 10(22), 8143, https://ouci.dntb.gov.ua/en/works/l1mwRvyl/

Gavarkovs, A. G., Blunt, W. & Petrella, R. J. (2019). A protocol for designing online training to support the implementation of community-based interventions. Evaluation and Program Planning, 72(2019), 77-87, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2018-61336-010

Kraiger, K. & Ford, J. K. (2021). The science of workplace instruction: Learning and development applied to work. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8, 45-72.

Longo, L. & Rajendran, M. (2021, November). A Novel Parabolic Model of Instructional Efficiency Grounded on Ideal Mental Workload and Performance. International Symposium on Human Mental Workload: Models and Applications (pp. 11-36). Springer, Cham, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354893819_A_novel_parabolic_model_of_instructional_efficiency_grounded_on_ideal_mental_workload_and_performance

Merrill, M. D. (2018). Using the first principles of instruction to make instruction effective, efficient, and engaging. Foundations of learning and instructional design technology. BYU Open Textbook Network. https://open.byu.edu/lidtfoundations/using_the_first_principles_of_instruction

Rea, E. A. (2021). "Changing the Face of Technology": Storytelling as Intersectional Feminist Practice in Coding Organizations. Technical Communication, 68(4), 26-39, https://g.co/kgs/XAhhL77

Schalk, L., Schumacher, R., Barth, A. & Stern, E. (2018). When problem-solving followed by instruction is superior to the traditional tell-and-practice sequence. Journal of educational psychology, 110(4), 596, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-57179-001

Shipley, S. L., Stephen, J. S. & Tawfik, A. A. (2018). Revisiting the Historical Roots of Task Analysis in Instructional Design. TechTrends, 62(4), 319-320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0303-8

Smith, P. L. & Ragan, T. J. (2004). Instructional design 3rd Ed. John Wiley & Sons, https://www.amazon.com/Instructional-Design-Patricia-L-Smith/dp/0471393533

Willert, N. (2021). A Systematic Literature Review of Gameful Feedback in Computer Science Education. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 11(10), 464- 470, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354317969_A_Systematic_Literature_Review_of_Gameful_Feedback_in_Computer_Science_Education