Why Donald Trump and Joe Rogan Are Not "Elites"

On populism as a different way of selecting who has power

Everyone talks about populism and elites, yet the way we use these terms has become somewhat strange. When we say “elites oppose Trump,” we don’t think there is anything off about this statement despite him being president and having established absolute dominance over one of our two major political parties. We usually refer to “populism” to indicate a movement that stands in opposition to elites, but that just brings us back to the question of what elites are. Fifteen years ago, that was an easy question, as we could simply point to the Republican and Democratic establishments and mainstream media outlets and say they were the ones with power and influence.

Yet today, Joe Rogan and Candace Owens get more viewers and listeners than CNN hosts, and Donald Trump controls the Republican Party like no other figure in American history. Nonetheless, we don’t say that the Joe Rogan Experience is elite in the same way CNN is. Somehow, Mitch McConnell, who now stands alone against the entire Republican caucus on high-profile votes, still seems more like an elite or member of the establishment than Donald Trump.

Can we have coherent definitions for “elites” and “populism” that correspond to how we commonly use these terms? I believe that we can. Elites are people who:

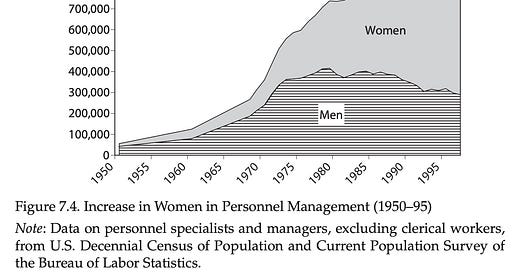

Participate in and have contact with long-standing, established institutions that have traditionally had cultural, political, and social power, even when the power of those institutions is waning.

Have status that is connected to their affiliations with such institutions or those involved with them, rather than a direct relationship with a mass audience, in terms of voters or consumers.

Have norms and professional incentives centered around raising one’s status via impressing other members of the elite, rather than a mass audience.

Once we have a definition of elites, we can define populism, which is a derivative concept. A good working definition of populism is that it is a worldview that:

Blames elites for societal problems and stands in opposition to them.

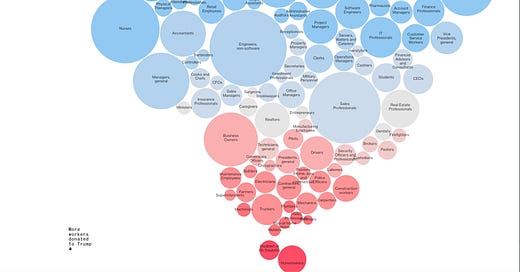

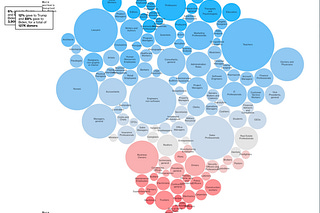

Champions values and aesthetics that have more currency among the general public than elites, namely xenophobia, traditional cultural values and forms of art, an openness towards mysticism and the supernatural, and a leveling informality in social relations.

Assigns status to individuals based on a direct connection to a mass audience or voters, rather than success within established institutions.

This definition pertains to right-wing populism, but it is reasonable to focus on that as left-wing equivalents do not have nearly as much influence in Western countries, mainly because for populism to be powerful you need to build a mass audience, which means believing in ideas that the masses accept but elites don’t. But left-wing views are already well represented in elite institutions. And the masses mostly care about identity and social issues, not economic theories, so even if it’s true that the public is more pro-redistribution and statist than elites, that is not enough to build something as popular as the Joe Rogan Experience or the Trump movement outside of establishment channels.

I think that (3) in each definition is what is key here and provides a new perspective on how to understand debates over populism, as knowing what status hierarchies people are part of goes a long way in explaining their outlook and behavior. Recently, I was interviewed by a New York Times Magazine staff writer. I looked him up and it turned out he had only a few thousand followers on X. I would love to regularly write features for the NYT Magazine, and even though as an individual I have a much larger audience than he does, I am unable to, and probably less “elite” in a sense. Yet his position depends on being associated with the NYT. If he were fired and couldn’t get another job at one of a handful of comparable institutions, he would see a precipitous fall in status and financial outlook.

Joe Rogan, in contrast, gets very little respect from the American Medical Association, CNN, the Council on Foreign Relations, the federal bureaucracy, or Pfizer. But he has an absolutely massive audience, and has much more influence over society than an individual NYT Magazine staff writer, though it is a more complicated question over how much power he has relative to the NYT Magazine as an institution.

Note that I said elites only have to participate in or have contact with certain institutions; they need not have formal associations with them. Andrew Sullivan now has an independent Substack. But he started out writing for major newspapers and magazines, still appears on Real Time with Bill Maher, and is read by and in dialogue with elites. He continues to have personal relations with them and cares about what they think. Individuals like Jesse Singal and Matt Yglesias are similar in these respects. Meanwhile, Michael Savage, Alex Berenson, Candace Owens, Glenn Greenwald, Darryl Cooper, and Jimmy Dore derive their status from the absolute sizes of their audience and are all populist figures in a sense.

Tucker Carlson spent two decades working for the big three cable news stations, yet now has his own show on X attacking the type of people who used to be his colleagues. Unlike Andrew Sullivan, he is no longer of elite status, since no part of Tucker’s income or sense of self-worth comes from gaining approval from elite institutions. If anything, the more they hate him, the more his status rises among his own audience and the more money he makes, creating a completely inverted incentive structure.

Donald Trump is a particularly interesting case. When he came on the political scene, he was opposed by big business, the media, universities, professional institutions, and both major political parties. He eventually became president twice because he had enough of a mass base of support. Now he has remade the Republican Party in his image, and staffed the White House, his cabinet, and the federal bureaucracy with toadies. It is tempting to call MAGA a new elite based on certain definitions of the term, but not the one that I think is most useful for understanding politics.

I think that a good way to illustrate the points made here is to look at how two individuals can hold the same position while one is elite and the other isn’t. Traditionally, FBI directors have served 10-year terms on the ground that they should not be tied to any particular president. And they generally have been impressive people. Before Kash Patel, consider the last 4 FBI Directors.

Louis Freeh (1993-2001), confirmed 95-0 in the Senate, JD from Rutgers, LLM from NYU

Robert Mueller (2001-2013): confirmed 98-0, BA from Princeton, JD from UVA

James Comey (2013-2017): confirmed 93-1, JD from the University of Chicago

Chris Wray (2017-2025): confirmed 92-5, BA and JD from Yale

Each one of these men got where they were by impressing other elites, from admissions offices of prestigious universities to members of federal law enforcement to Senators. Freeh had the least impressive academic credentials, but worked his way up from FBI special agent, to Assistant US Attorney, to federal judge, and finally FBI Director.

Kash Patel, in contrast, earned his BA from the University of Richmond and his JD from Pace University, currently ranked 136 among law schools. He began his career as a public defender, and did not particularly distinguish himself before getting his current job, except as a pro-Trump partisan. He had several sources of income before he was selected to run the FBI, including children’s books on how everyone should worship Trump, Trump shirts, and consulting fees from Truth Social and a Trump Super PAC. As a side note, he’s also been selling supplements that supposedly reverse the negative effects of vaccines.

Patel became FBI Director by a 52-48 vote, being opposed by all Democrats and McConnell. Even the way he was appointed violated norms, with Trump having forced out Wray before his term was up for not being enough of a stooge. Wray had replaced Comey, who was fired by Trump in 2017. Before that, only one FBI Director in history had ever been removed, William Sessions in 1993, and that was due to a straightforward ethics scandal not having to do with anything related to loyalty to the president.

While previous FBI Directors impressed other elites, Kash Patel’s activities have been aimed at winning over the approval of one man, and he has succeeded at this goal. This has involved moving through MAGA circles, including the podcast circuit, as a way to build his own base of support and get the attention of Trump himself. Since J Edgar Hoover died until now, all subsequent presidents and FBI Directors had tried to create the impression that law enforcement was independent of the head of the executive branch. Comey reportedly refused to play basketball with Obama on these grounds. Meanwhile, when Patel was appointed, one of the first things he did was start asking what was the most secure way to directly call Trump from his home and office.

Populism can therefore be seen as a shortcut to power. Nobody at the NYT or an academic journal would ever ask Candace Owens to publish an article, but she can go to YouTube and build a massive audience. Donald Trump would not have been selected by GOP leaders in 2016, but he had a direct connection to the voters. Kash Patel didn’t get into an elite school or work his way up through the FBI, but he was willing to kiss up to Trump like no one else.

This explains why the populist style and certain substantive positions go together. Elites pride themselves on being tolerant of outsiders, which makes them favor things like more liberal immigration policies and DEI programs. They trust scientists as a default and tend to reject conspiracy theories. Thus, we see alternative medical theories, conspiracies, mysticism, and anti-wokeness, if not straightforward racism and misogyny, as central to the populist worldview, since these are positions that are undersupplied in a marketplace of ideas when it is dominated by mainstream institutions.

Ironically, while populists rail against elites and often accuse them of wielding arbitrary power, when they get control over institutions they are often even less restrained. For example, a president and FBI Director working in tandem, with the latter’s position completely dependent on the former, can more easily target their political opponents than a president and FBI Director who never talk to one another and are afraid to be seen in the same room. In shaping public opinion, Joe Rogan and Tucker Carlson can do more to advance preferred narratives than any individual New York Times writer, and won’t see their message filtered by editors and other kinds of intermediaries.

All of this raises a question: now that the Republican Senate is voting to confirm Trump picks like RFK, Tulsi Gabbard, and Kash Patel, why isn’t MAGA the new elite? In 2017, Trump faced pushback, but now the party has become so MAGAfied that he has much more control over what Congress does. Even at lower levels of staffing the bureaucracy and White House, loyalty to Trump has become much more important this time around than it was in the first term. It’s Trump’s party now, which raises the possibility that MAGAs are a new elite.

Yet while Trump has remade the Republican Party, it is still generally isolated among powerful institutions. Imagine if say Dartmouth was somehow taken over by populists, who went and replaced all of the administration and faculty with true believing MAGAs. It would be an island unto itself. Moreover, Trump’s hold on the GOP would be fragile if not for his direct connection with his base. It seems likely that if the Republican congressional caucus, even in its current state, could have picked the party’s 2024 nominee through a secret ballot, Trump would have had a much tougher job emerging victorious than he did in the primaries. This means that Trump, and therefore figures like Patel selected for their loyalty to Trump, continue to depend on a direct relationship with the masses rather than elite approval. If Trump lives thirty more years and remakes the Republican Party even more in his image, then at some point MAGA starts to resemble an elite, though even then only to a limited extent as long as they do not also control institutions other than those that are explicitly tied to the conservative movement.

With this framework in mind, we can begin to form an opinion about whether populism is a good or bad thing. To be on the pro side, one has to believe that institutions are hopelessly broken and cannot be reformed from the inside. Things are in fact so bad that a person making their way up the ladder must have some kinds of fatal cognitive and personality flaws that make them unfit to exercise power. Think Buckley’s famous idiom that he would rather “live in a society governed by the first two thousand names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the two thousand faculty members of Harvard University.”

That said, populism does not mean choosing who to elevate to positions of power at random, but rather doing so based on factors like ability to get votes without institutional support, social media clout, and willingness to kiss up to Trump. The question is whether these are the kinds of strengths that should replace other mechanisms that have traditionally determined who has power in terms of what experts to listen to, what forms of media are considered credible, and who is voted into office and staffs government bureaucracies.

Do we want our ruling class to have gone through selection pressures involving the judgment of other elites, or do we want them to have a direct line to the masses based on personally cultivated audiences and their ability to win elections in the face of elite hostility? This is important because we cannot observe what powerful people are doing all the time. How do you know that federal law enforcement doesn’t go around planting evidence on people it doesn’t like, or selectively prosecuting them? Or that any particular journalist you are listening to isn’t making things up? Power brings an endless number of opportunities for abuse, and it is therefore important to make sure people we can trust are elevated to high positions. Who is more likely to engage in corrupt practices: a man who has no hint of scandal in his past and can get nearly all Senators from across the political spectrum to agree he is a suitable choice, or one who writes Trump children stories, is a hit on the MAGA podcast scene, and can only get through the Senate on an almost straight party line vote, and only that because Republican politicians fear the wrath of Trump? Only by first realizing that Kash Patel leading the FBI is the natural result of populism can we begin to form a reasonable opinion of its merits.

The elevation of Elon Musk to shadow president, and his continued presence in that role, proves to me beyond any shadow of a doubt that the Trump movement is not a serious option for governance. The incompetence and stupidity on display are absolutely staggering, and the constant apologetics for it leave me at a total loss for words. I certainly don't want the left back in power, but if this is the alternative, I don't know what to say at that point. It seems that the consequences of social media for politics have actually been far worse than anyone could've predicted.

I've now been thoroughly convinced that Trump's rise to power and takeover of the GOP was for the worse, in a big way. I'd much rather have Mitt Romney's Republican party back.

I think of populism like acid. You need an occasional flush of populism to clean out the corrosion of elite institution pipes due to arrogant group think, outdated orthodoxy, suboptimal filtering and patronage networks, and conflicts of interest. But just as too much acid can end up destroying pipes rather than just clean them, populism becomes destructive when it becomes excessive or an end unto itself. Ideally populist movements will be short-lived and cause elites to self-reflect, clean up their institutional defects, and then make the elite ranks effective and respectable again.

Disaster strikes when either the elite arrogantly reject any legitimate criticism, leading to revolution (think 1789 France and the "divine right of kings" doctrine), or when the commoners refuse to acknowledge the good faith efforts of elites to improve, instead succumbing to a mob mentality that glorifies the "will of the majority" over all else.