10 minute read

Reconnecting a divided nation

Today’s U.S. is a deeply polarized nation. Many observers say we have not been this divided since before the Civil War. Perhaps the greatest divide is between major metropolitan areas close to the coasts, and rural areas and smaller industrial cities in the heartland. At the root of this chasm is a sense those latter areas have been left behind. The term, “fly over people,” captures the essence.

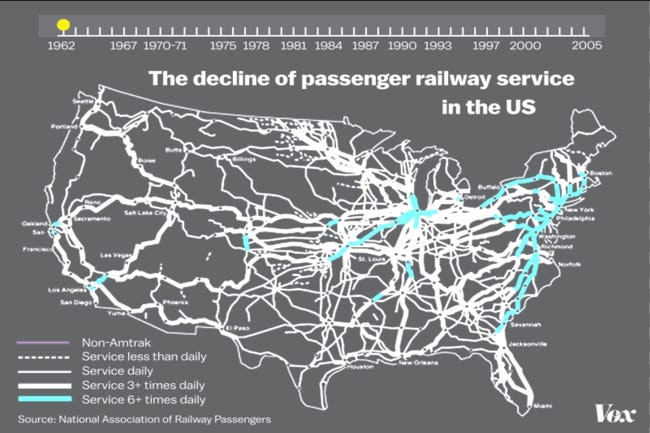

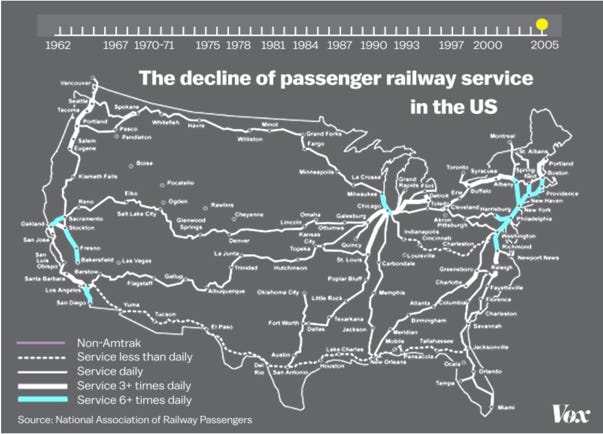

Within that phrase is a reference that is not often noted, but hiding in plain sight. “Fly over” refers to a mode of transportation, aviation, that connects major metropolitan areas. Indeed, many smaller airports have lost scheduled flight service, and that which remains is often inordinately expensive. Meanwhile, other forms of intercity transportation linking smaller communities have also diminished. Bus service is not what it once was. And rail service is often a shadow of what it once was. As life has more and more centralized in the large metros, access for rural and smaller communities by other than by private automobile has declined. For instance, healthcare often requires long drives to metropolitan facilities.

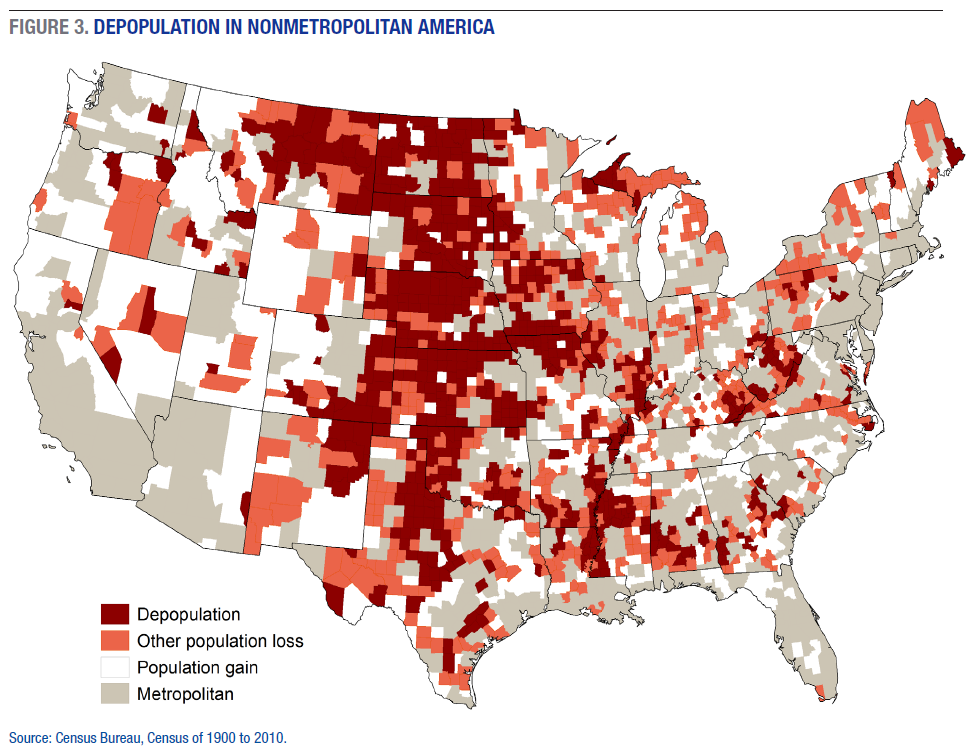

The result is an economy drawing apart into prosperous metropolitan areas and rural areas afflicted by depressed conditions, decaying buildings and infrastructure, and conditions of despair that contribute to declining life expectancies in the U.S. due to causes ranging from drug overdoses to increasing suicides. Overall, the consequences create a political polarization in which people can barely talk with one another. While many circumstances contribute to the economic decline of rural areas and small industrial communities, including automation and international trade, one solution without which others are impossible is improved transportation access. To build a future for the vast swathes of the U.S. that are being left behind, and begin to heal cultural and political divides, we need to reconnect America. For that, we need to look to our past, when railroads connected all parts of the nation.

Rail at the center of U.S. history

Railroads stand very near the center of U.S. history. It can hardly be told without them. Railroads connected a continental nation, indeed, made it possible.

When Thomas Jefferson sent the Lewis & Clark expedition to the Pacific Coast, he could not conceive a coast-to-coast nation. Believing governance across such a vast expanse was no more practical than had been administering the 13 colonies from London, he envisioned the coast would become a “great, free and independent empire,” a companion nation settled by people from the U.S.

The emergence of the steam-powered railroad changed that picture. Though early conceptualization began in Jefferson’s time, it was not until 1825 that the first passenger-carrying public railroad propelled by steam engines began operating, the Stockton and Darlington in northeast England. The U.S. followed a few years later in 1830 with its first intercity railroad, the Baltimore and Ohio. Then, in 1845, China trader Asa Whitney unsuccessfully proposed to Congress that he be granted a 60-mile corridor through public lands to build a railroad to the Pacific. That brought the idea to the fore, but it was not until 1862, under the pressure of the Civil War and the need to link up the nation, that Congress finally approved the idea, leading to the joining of the nation coast-to-coast at Promontory Point, Utah May 10, 1868.

Railroads made possible the white settlement of the west, though it must be acknowledged with tragic consequences for native peoples. Railroads also propelled the U.S. to become the leading industrial power and economy in the world. Without the railroad, the U.S. would not have risen to global leadership.

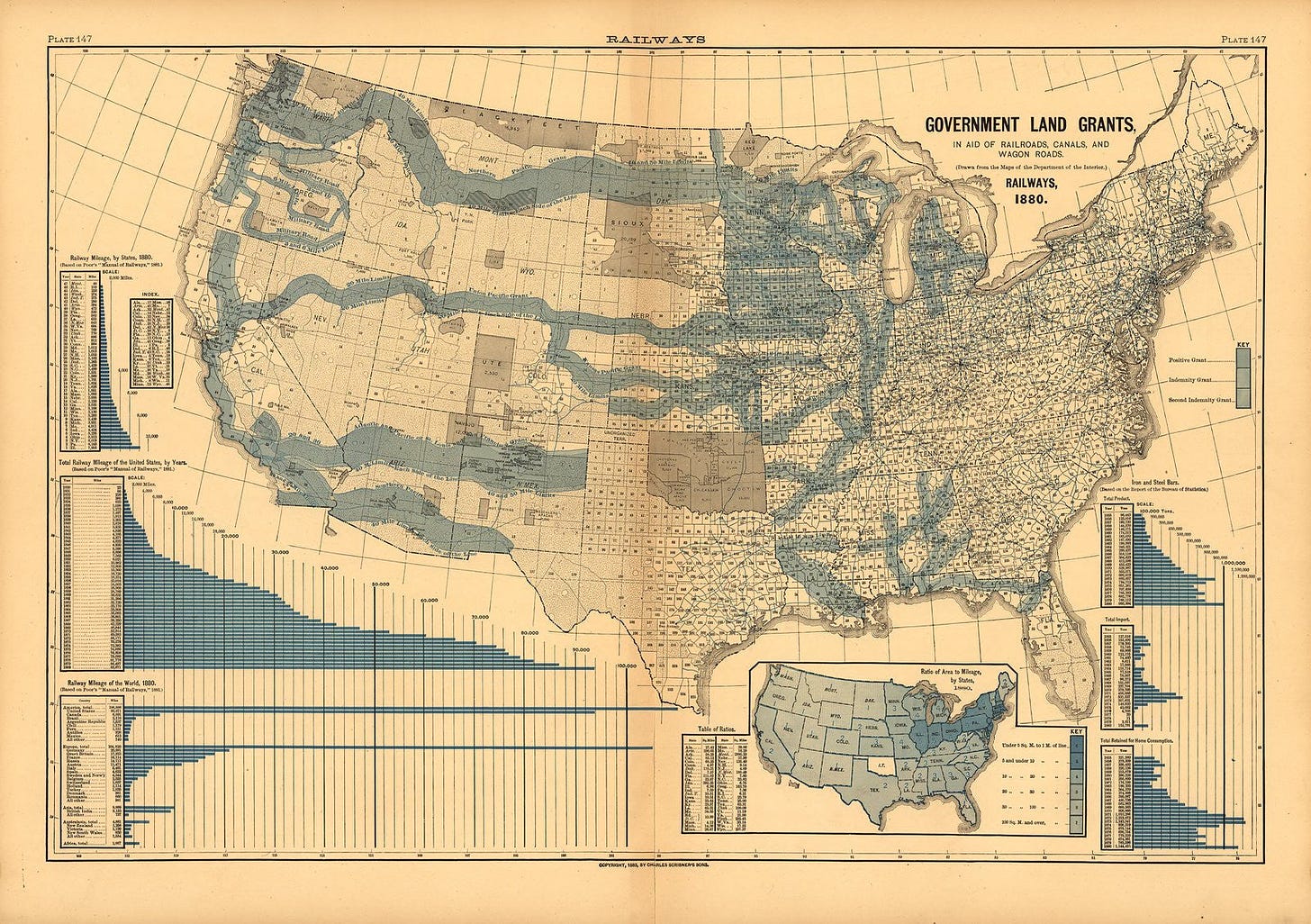

Railroads are not just another industry. They are part of the connective tissue that weave the U.S. together. Through the history of the U.S. they made possible the development of agriculture and industry across a continental expanse, as well as making governance of a continental nation possible. Recognizing their vital role, the federal government provided massive land grants and financial support to extend railroads beyond the Mississippi to the Pacific Coast. The first major industry to be regulated by the federal government, railroads have long been recognized to have a responsibility beyond making profits for their owners. Rail must operate in the public interest.

Railroads have always been a public-private partnership. They were created by the public to serve the public. Railroads were given almost a tenth of all land in the contiguous United States to fund their expansion, and that expansion helped build the country. Many towns would not be where they are today if there had not been a railroad there first. These railroads connected America.

Abandoning smaller communities

Railroads once connected us all. They had an obligation to move the people and products of rural and urban places under common carrier responsibilities. Starting in the 1970s, railroad deregulation relieved them of that duty, and people who lived in rural areas and smaller communities were left behind. Instead, railroads cut out less profitable services in pursuit of increasing returns for Wall Street shareholders. Railroads were consolidated and deregulated, and the result was that they no longer even had to stop in the communities they had served for decades. Now they only stop for those who can muster 110 fully loaded bulk cars, which is almost no one. So they usually just speed on through on ever-longer tracks, if they come at all.

In abandoning all but larger shipments, railroad companies have moved away from the mixed freight markets they once served. Those markets have increasingly been taken over by trucking, which increases costs for both farmers and industries, putting them at a competitive disadvantage with larger agribusiness and metropolitan manufacturers. Railroads are interested in bulk commodities and containers from international ports, which provide then a higher profit rate.

If you live in a rural area or smaller community, this leaves your people and your products stuck, forced onto trucks that charge a high rate and wear out your county road. Businesses and farms who can’t play along end up folding or getting swallowed by unaccountable transnational corporations that do not see you, hear you, or care about you. Local businesses lose their most reliable customers. People pack up and leave town or stay and do what they can to make it work.

Railroads once connected all communities in America with a robust circulatory system. Under deregulation and abandonment of common carrier responsibilities, the system was reshaped to be a superhighway for globalization, offshoring, and outsourcing. Since 1970, total route miles have dropped from 196,000 to 140,000. Fifty-six thousand miles of rail were just abandoned, with 39,000 more being spun off into small, short line railroads that have struggled to keep those tracks in operation. People outside of major metropolitan areas have been left behind.

Reconnecting America by reviving rail

Today we need to be connected again. Any serious effort to “re-shore” U.S. manufacturing and agriculture to address the supply chain crisis and related issues must include the return of rail service to communities, farmers, and industries left behind in the rush to serve the globalized supply chain.

We need strong, resilient local communities, family farms, innovative and nimble manufacturing that doesn't require crossing an ocean. Railroads can connect us. They can move people, food, and manufactured goods. Not just to overseas markets, but to people in this country. Trains are highly efficient and require far less energy than trucks, and should be used to avoid wear and tear on our roads. They are a beautiful way for people and families to travel, for people who can’t afford a car to get to work or to school, for our elders and loved ones to get the medical care they need. Railroads can revive the circulatory system that trucks have sustained only at an enormous cost to public budgets.

Rail corridors are also the ideal way to electrify freight and passenger transportation without needing to mine for batteries and deplete resources in far off places. Electric rail is faster, lighter, more powerful, and cheaper to procure, operate, and maintain than diesel-powered trains. It can carry more weight more quickly, and at a lower cost. Electric locomotives are also quieter than diesel-powered ones and zero-emissions at the point of use, meaning they do not create diesel death zones around railyards—clusters of cancer, asthma, and other severe health problems in already-disadvantaged communities.

The United States once led the world in rail electrification. The 654-mile Milwaukee Line was the longest electrified rail line in existence. It possessed what was called the “World’s Mightiest” locomotives because they could ascend slopes far steeper than what steam engines could handle. The Milwaukee Line ran for 57 years, from 1917 to 1974, and attracted engineers from all over the world. At the same time that this technology was dying out in the United States, it was being adopted everywhere else. Today, several countries have electrified 100 percent of their tracks. Russia has electrified over half of its rail miles; China has electrified two thirds, amounting to 62,000 miles, just in China.

Rail’s renewable energy opportunity

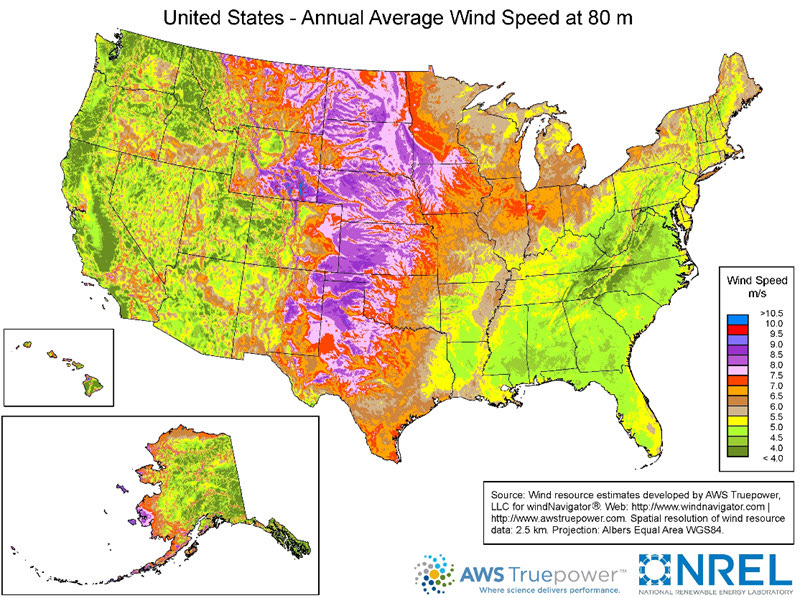

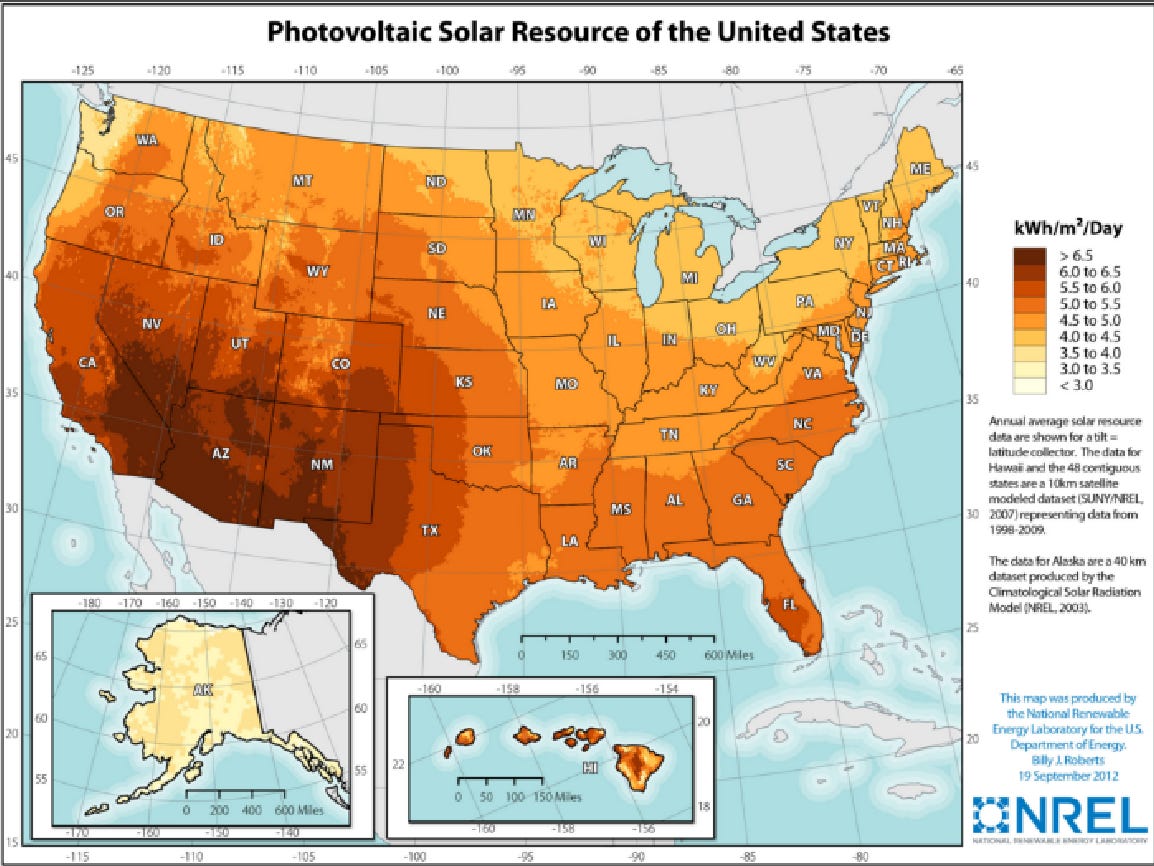

Our railroads were never just train tracks—at least not originally. The Transcontinental Railroad was also created to serve as a telegraph line. Today, we can build an electrical transmission network along our railroads, adding the infrastructure we need to transition to a fully renewable energy grid. Solar and wind resources tend to be situated far from major metropolitan markets. Developing them represents a tremendous economic opportunity for rural people needing a new jobs base, and for rural landowners who can earn large payments leasing their property.

A small handful of states have enough sunshine and wind to power the whole country many times over. The only thing preventing this is the lack of a sufficient transmission network. To fully access solar and wind potential we need to expand transmission. But the need to run new lines across many private ownerships, along with local opposition that often rises, poses obstacles. Rail corridors provide a singular ownership long in industrial use, avoiding those difficulties.

By electrifying our railroads, we can connect our communities with renewable energy at the same time that we connect people with their basic needs—and with each other. Electrified railroads can provide the infrastructure we need to transmit renewable energy from the wind and the sun throughout the country, providing a reliable national super-grid of clean energy and opening up new markets in wind- and sun-rich regions across the country—often precisely the regions that have been left behind economically.

Rail in the public interest

To realize these opportunities to reconnect America, we must revive the public interest responsibilities of rail lost in the drive to serve Wall Street shareholders. A railroad network that operated in the public interest could realize tremendous benefits for climate, human health and efficiency of movement. It could open up new economic development possibilities for rural America, many parts of which are stuck in permanently depressed conditions. It is clear that the current ownership system is not realizing these opportunities. For rail to fully serve the public interest, the public is going to have to get more involved. Four major options are being considered.

One is re-regulation. The federal government could restructure its regulation system to mandate that railroads meet their common carrier responsibilities and once again serve markets and customers they have abandoned. It could also require pollution reductions leading to electrification. But regulatory systems have been subject to capture by the industries that they regulate, and whether regulation could fully drive railroads to serve public interest goals is a question. It would certainly cut into profits.

Another is vertical separation. In this scheme, railroad operations and trackage would be divided into different business units, or different businesses entirely. Tracks would be open to all rail operators in an open access-toll road arrangement. But whether this would overcome the profit-driven obstacles to electrification is doubtful. And there is no guarantee that underserved markets and customers would see full restoration of service.

A third is total nationalization of the rail system. It would be costly, while political will to achieve it against railroad company lobbying and legal action would be hard to accumulate. If achieved, a full range of passenger and freight services could be restored, while public investment could make electrification a reality. But it would be a process of many years.

A fourth option is a hybrid of the second and third. In it, railroad companies would be offered the option of buying out their track infrastructure, while they could still operate on the lines. The federal government would take over maintenance to create a Steel Interstate system that could eventually evolve to run most or all of the primary rail lines in the U.S. Since most are under control of just four railroads, this would be quite feasible. Railroads would be relieved of the burden of maintenance to focus on their operations profit centers. Thus they would have an incentive to join the system. Meanwhile, the Steel Interstate would operate as an open access-toll road system, creating the possibility for entrepreneurial players to offer services primary railroads have abandoned. Public agencies could also offer services such as enhanced passenger connections. Meanwhile, to serve climate and environmental goals, the public could invest in electrification of the whole system.

Of these four, it seems most likely that the fourth could realize the public interest potentials of the rail network effectively without the drawn-out battles that full nationalization would entail. It would also open the system to entrepreneurial initiatives that would not exist in a fully nationalized system. This hybrid system already operates in Europe, where nationalized rails are open to multiple operators.

Rail to Reconnect America

In the history of the U.S. rail has provided the vital links on which the country grew. It made a continental nation composed of prosperous communities possible, cities big and small, and rural areas. Rail’s abandonment of its public interest responsibilities has played a large part in the decline of rural areas and smaller communities, helping to supercharge political and cultural polarization.

Reviving rail by calling it back to serve the public interest can play a key role in healing those divides. It can level the economic playing field for communities beyond the major metros, building a new basis for prosperity by improving access to them. By leveraging rail electrification for long-distance transmission of solar and wind energy to metropolitan regions, a rail revival can hugely contribute to addressing the climate crisis, one of the greatest facing the 21st century world.

Reconnect America is a project for us all. Along the tracks of a rebuilt, electrified rail network, we can make it happen.

Join the Solutionary Rail team

Be part of this people-powered campaign to put American railroads in service of the public interest through rail electrification, shifting freight and people from roads to rail, and using rail corridors to transmit renewable energy. Participate in webinars, strategy sessions and skill sharing with community and technical experts by signing up at SolutionaryRail.org. Support this work with a tax-deductible donation here.

"From the moment I understood the weakness of asphalt, it disgusted me. I craved the strength and certainty of the Steel Interstate. I aspired to the purity of the Blessed Dynamo. Your kind cling to your trucks, as though roads will not decay and fail you. One day the crude biomass you call fuel will run dry, and you will beg my kind to save you. But I am already saved, for the electron is immortal… Even in death I serve the Conductor."

If the government owned the trackway, there would be constant fights in Congress about appropriating enough money to maintain it well. And the truth is that the lands granted to the rail lines are long gone from their ownership. They have narrow strips of land a few dozen feet on either side of their tracks today, most of which pierce dozens of small towns in each state they cross. Those small towns are not going to want very high tension lines marching through their cores. Sure, some ROW's could become transmission corridors, but out west where the generation is so productive there are only a few lines.

For instance, to get juice out of Arizona to the Midwest one would need to use the BNSF or UP trackways to the east and northeast. You have to get beyond Clovis and El Paso before there are more than two corridors. Even if you used Megavolt transmission on it, that's not all that much capacity.

Wind power out of eastern Wyoming is somewhat easier, because there are several decrepit "granger" routes that might be useful, but, again, the "devil is in the details", especially east of the Missouri where there are lots of railroad rights of way but also LOTS of little towns along them.