There Are Signs of a Category 5 Housing Crisis Forming and Coming Straight For Us

The tentacles of a homeowners insurance crisis are far-reaching

If there was ever a “canary in the coal mine” moment for the next housing crisis, it’s that mortgage and insurance giant Fannie Mae maintains a secret mortgage blacklist.

The Wall Street Journal broke the news on March 17 that Fannie Mae keeps a blacklist that includes condo associations it believes have too little property insurance or need to make critical building repairs. According to the Journal, it’s a list that every major lender pays attention to.

In other words, if you’re buying a condo in a building on that list, you’re likely not going to get a loan. However, the insurance “canary” isn’t just about condo buildings.

If you think homeowners insurance has already skyrocketed — and it has — hold on because you’re likely about to get screwed even more. First, some background:

The power of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae

These three agencies insure against losses on about 90% of all residential mortgage loans. These loans end up as mortgage-backed securities (MBS), which amount to more than $9 trillion.

The liquidity of the MBS market is the main reason getting a home mortgage in the U.S. is relatively easy. Without agencies like Fannie Mae, our housing market would be a fraction of what it is today. When borrowers make the monthly payment on their loans — usually to a loan servicer — the monthly payment goes through the agencies and makes its way to the MBS market.

The agencies guarantee against principal losses and collect a monthly fee called a “Guarantor Fee.” In this case, they’re acting like an insurance company to MBS bond holders by collecting premiums and paying out any losses due to borrower default. MBS are collateralized by the borrower’s home.

Therefore, if the homeowner’s insurance isn’t paid, then the collateral (ie: the home) backing the loan is at risk. If a home that’s collateralizing a mortgage that the agencies guarantee is without insurance, and the home is destroyed, the agencies would take the loss.

A lapsed insurance policy can be considered a default and lead to foreclosure.

Insurance and mortgage rates are connected

Homeowners insurance is going up. A Treasury Department report released in January found that, nationally, insurance rates rose 8.7% faster than the rate of inflation from 2018-2022.

Of course, the agencies can’t guarantee large swaths of homes in securities unless they are insured.

Most people’s mortgage payment includes their insurance premiums and real estate taxes. Those premiums and taxes go into an escrow account from which the loan servicer pays those bills when they are due. So, as your insurance premiums and real estate taxes go up, so does your mortgage payment.

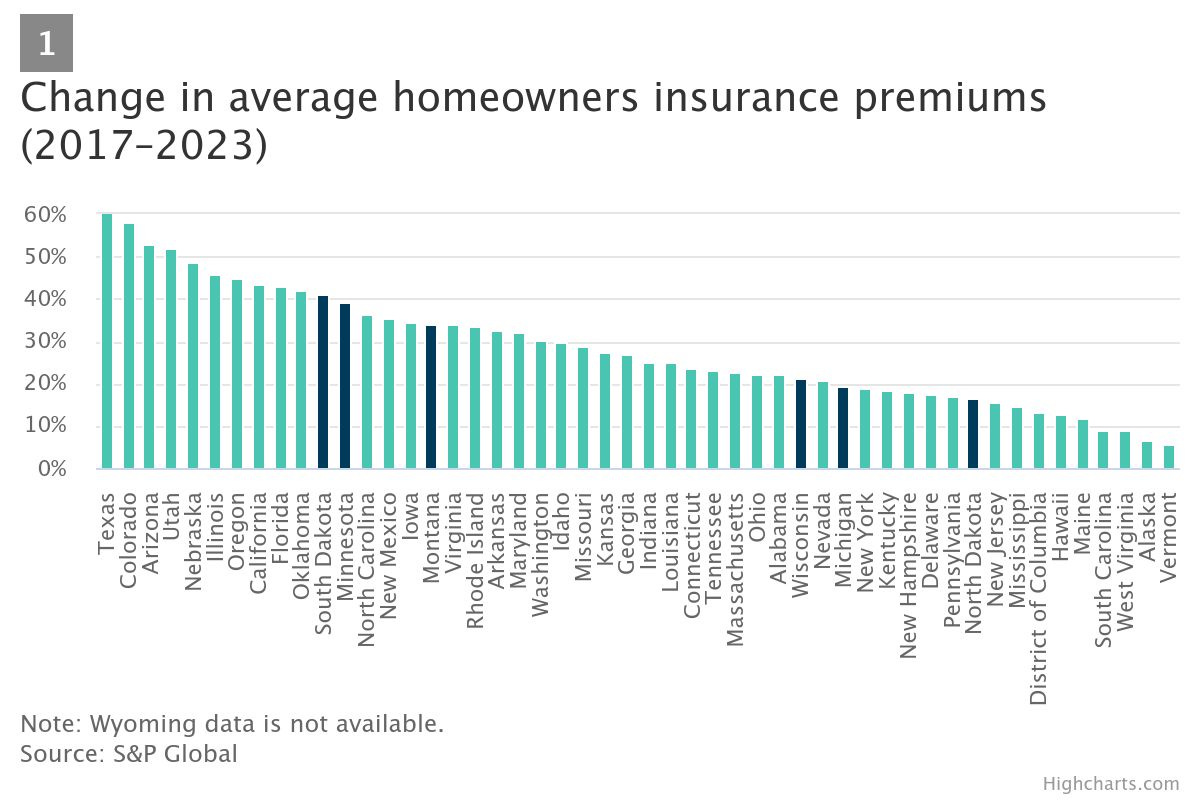

This is where the rubber meets the road. While the average price of insurance went up 8.7% more than inflation from 2018-2022, it went up 14.7% more than inflation in the 20 highest-risk zip codes. The consumer price index rose 20% during that period. That means a $1,500 insurance policy in those top 20 zip codes increased an average of $344, raising a monthly $3,000 payment to $3,029. Another study from S&P Global found that premium increased an average of 34% from 2017-2023:

If you can still only pay the $3,000 a month, you’re delinquent even if you covered your principal and interest in your payment. That means you’re on the path to foreclosure.

Often, homeowners in this situation get introduced to a dark corner of the financial world: Forced Place Insurance (FPI). When closing on a home, the borrower signs loan documents agreeing to maintain continuous homeowners insurance coverage. If the insurance policy lapses or gets canceled, the lender or servicer steps in and obtains FPI — also known as lender-placed insurance — to safeguard the property.

FPI premiums are usually four to 10 times more — meaning even higher monthly mortgage payments and an increased likelihood of default. That’s starting to happen in the commercial real estate market.

FPI played a big role in the 2007-2008 mortgage crises, as Rohit Chopra, the former director of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, noted in this 2023 speech:

There have been numerous lawsuits against mortgage servicers and insurance companies alleging that these entities, or an allegedly captive reinsurance company, were paid kickbacks. Even if the mortgage servicer doesn’t profit from the force-placed insurance, the mortgage servicer has limited incentives to minimize the cost of the force-placed insurance or avoid the placement. The entire price of the force-placed insurance is then passed on to the borrower.

Foreclosures

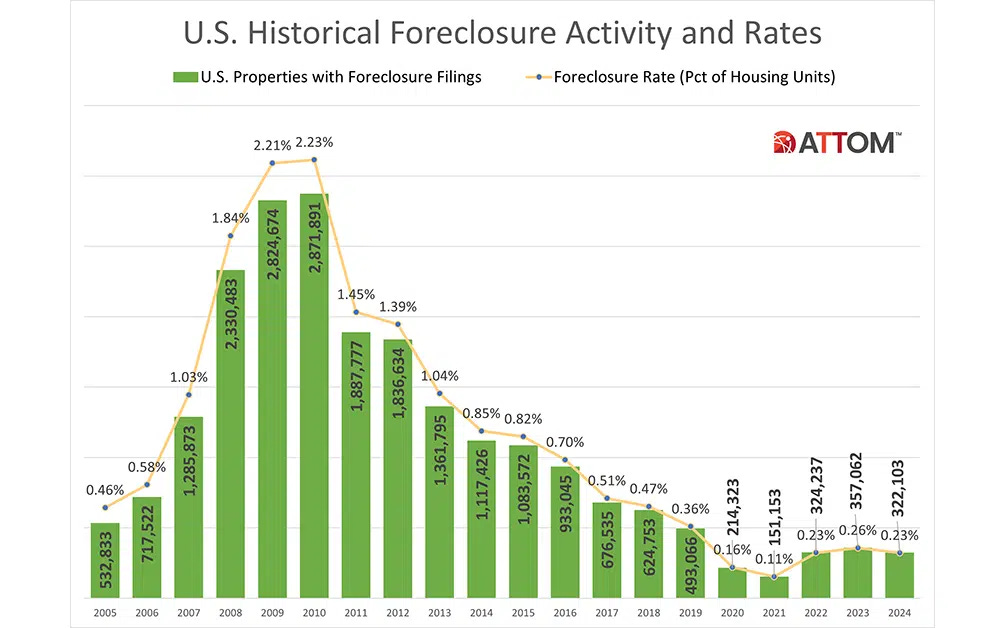

Look what’s happening so far in 2025:

Foreclosures 2025

January: +8% from previous month

February: +5% from previous month

While foreclosure numbers year-over-year are still below 2024, and the rate has remained relatively unchanged the previous three years, I’m concerned the uptick could become a trend because we know insurance rates have been going up since 2022, the last year covered in that Treasury Department report. The average premium jumped nearly $200 in 2023 and jumped again last year, according to this report from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies.

With premiums rising faster than inflation, something’s got to give. I’ll be keeping a close eye on the foreclosure report for March later this week.

Higher insurance premiums = higher mortgage rates

Most of the media’s attention focuses on the Fed when it comes to mortgage rates. But insurance premiums can also affect rates for a new loan.

Any loan provider is going to look at where the agencies’ securities are trading. If they are yielding 6%, the loan provider can’t just sell the loan at that rate. They also have to add on that guarantor fee I mentioned earlier that guarantees investors won’t lose money on the loan’s principal. There’s also the loan servicing fee. That 6% rate is likely to become a 6.75% rate for the customer. The higher the guarantor fee — which is in this case affected by soaring insurance premiums — the higher the interest rates. This FHFA report released last May shows that Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae guarantor fees are going up.

Of course, insurance premiums are on the rise in large part because of natural disasters. Let’s face it: these days it seems like most of the country is increasingly prone to fires, hurricanes, or tornadoes. If you’re in California — which has been dealing with an insurance crisis for several years — your rates are already going up because of January’s fires in the LA area.

I don’t need to tell you that disasters increase insurance premiums no matter where you live.

But not to worry. The Treasury Department had a remedy in that January report:

State and federal regulators and policymakers should continue their efforts to improve public awareness about the importance of adequate homeowners insurance.

To quote Steven Wright, “I couldn’t repair your brakes, so I fixed your horn instead.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct an error we made in calculating an increase in monthly mortgage payments resulting form higher homeowners insurance premiums. We also added additional information from a study that the Minneapolis Fed wrote about last year.

I get the point of the article. But if insurance rates go up 10%, your entire mortgage payment which includes principal, interest, insurance, and property taxes doesn't go up 10%. Of that $3,000 monthly mortgage payment, maybe $140 is the insurance. Meaning that that payment would go up $14 a month to $3,014, not $3,300.

Your math is wrong. If insurance goes up 10%, how does my payment go up 300 a month unless my insurance is 36,000 a year. Your also mixing up mortgage insurance with property insurance. I’d take this article down and a financial professional review it before reposting.