The Internet went to Threads last week, literally. And I did too.

I signed up for Threads, the hot new social media platform, on the very first day. And I joined with innocent enthusiasm.

Although I’ve been a critic of Mark Zuckerberg in the past, I do want him to succeed. We would all benefit from that.

Do we really need more social medial platforms? Maybe not, but we definitely deserve better ones—genuine communities that empower users, instead of manipulating them. A little bit of competition in this oligarchic field must be a good thing.

The Honest Broker is a reader-supported guide to music, books, media & culture. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription.

Time will tell whether Threads can surpass Twitter and other social media platforms. But it is already a useful indicator of the new Internet.

I say new Internet because the online world has changed a lot since Mark Zuckerberg launched Facebook out of his Harvard dorm room in 2003. Just consider the company’s original mission statement:

“To give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.”

That’s a lovely goal—but Zuckerberg changed his mind in 2017. He explained the reasons in a 5,800-word letter that was a lot more confusing than those 15 crystal clear words.

In this rambling letter he used the term “social infrastructure” 14 times.

He never actually defined what “social infrastructure” means—but I think it’s what replaced the notion of community on social media.

Now the launch of Threads offers us some valuable insights into what social infrastructure looks like in the year 2023. Above all, it makes clear that “giving people the power” is no longer a priority for web technocrats like Mark Zuckerberg.

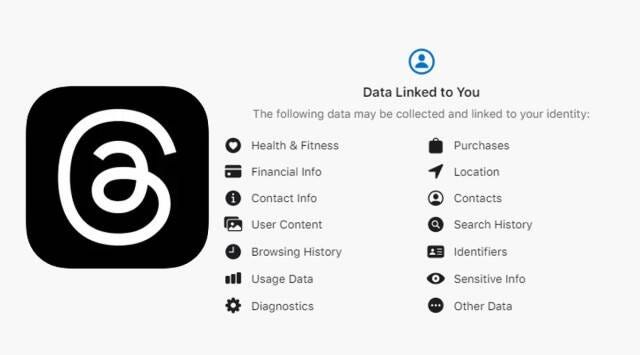

In fact, the first thing you do when joining Threads is sign away your rights.

I thought I couldn’t be shocked at invasions of privacy any more. But even I had to shake my head at the last item on the list. After agreeing to surveillance by stealth of my health and wealth, as well as location, browsing history, and the catch-all “sensitive info,” the company still had to add “Other Data” at the bottom.

Mr. Z. could have made it simpler. Just tell us we have no private information whatsoever and be done with it.

This feels more like an arrest than an invitation to join a cool new community. The only thing missing was a reminder of my right to an attorney and a warning that anything I say “can and will be used against me in a court of law.”

All this was distressing. But I decided to sign up for Threads anyway.

I guess I still have the right to remain silent. In a world of all-encompassing social media, that’s useful to remember. But I’m like those blabbermouth crooks in the TV police shows—I started talking on Threads as soon as I got the chance.

This feels more like an arrest than an invitation to join a cool new community. The only thing missing was a reminder of my right to an attorney.

But tracking what we do is no longer enough. The real goal of the new Internet is herding community members like sheep. Facebook is now the expert at this, as I recounted in my sad memoir of “ten times Mark Zuckerberg jerked me around.”

Will he really do the same thing to me on Threads? I guess I’m going to find out.

The next key point about Threads is the “Hotel California” clause—you can check it out whenever you want, but you can never leave.

The platform’s “supplemental privacy policy” makes this very clear:

You may deactivate your Threads profile at any time, but your Threads profile can only be deleted by deleting your Instagram account.

Many Threads users have large followings on Instagram—in fact, this is how Mark Zuckerberg plans to build his new platform. But even if you just want to try out Threads, you are now locked into it—unless you’re willing to nuke your Instagram presence.

I learned of more limitations after joining the club. In fact, the list of what you can’t do on Threads is long.

Some of the constraints are strange. Why can’t I know if my post has been shared by another user? Why won’t Threads let me find out how a post went viral—or even if it went viral?

One power user found this totally befuddling:

A key feature that does not exist on Threads is you can repost—essentially a retweet or quote tweet—but you don't see that count, and you don't get notifications about it. So when you have something like this post that went viral I could see I was getting a lot of replies to it, but I could not see how it was spreading. And that's a very interesting, weird dynamic.

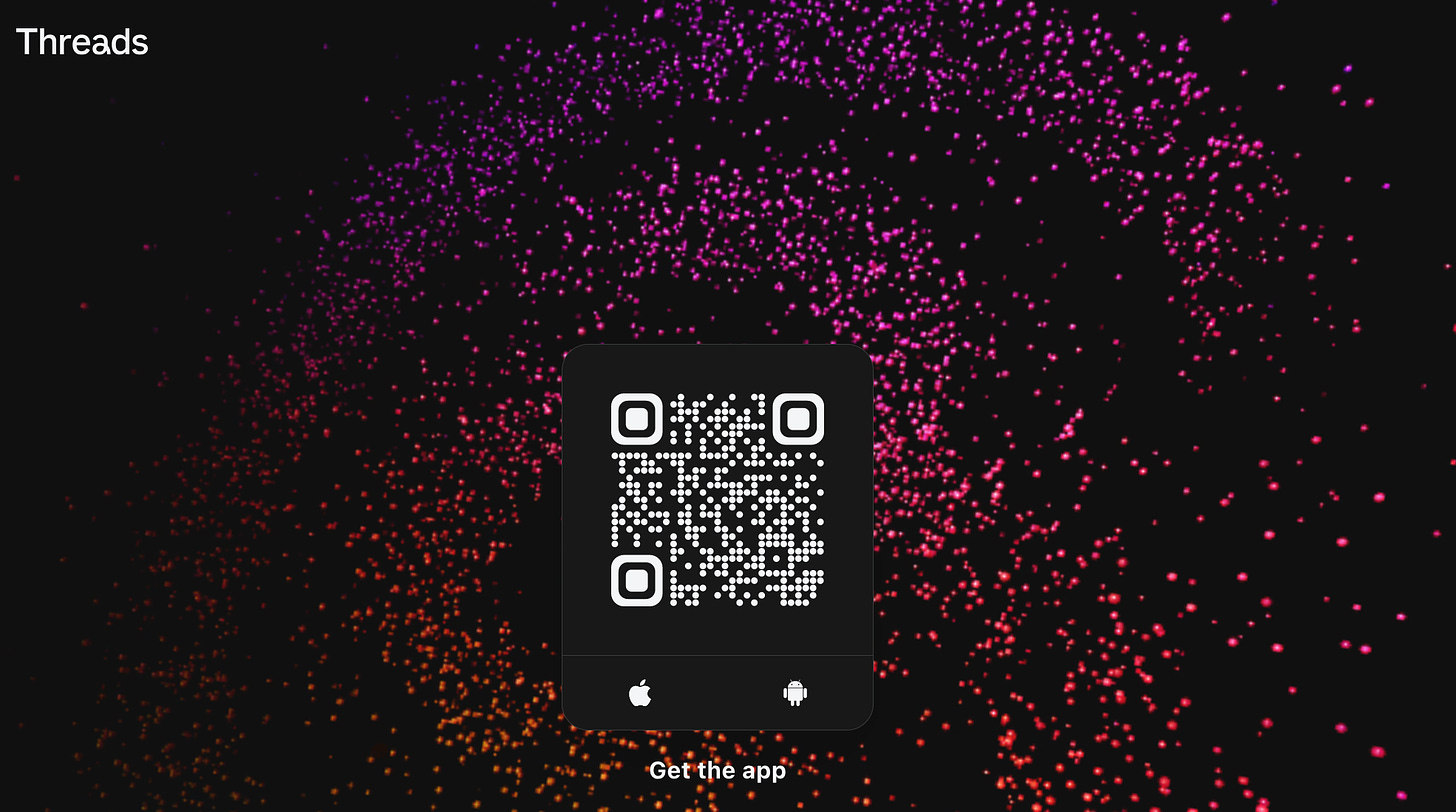

Or why can’t I access Threads with a desktop or laptop computer browser? If I try to do it, I encounter this.

That’s the entire text—”Get the app.” Not even please or thank you or any explanation. Just an order.

When I studied Latin, I learned that the verb “get” in “get the app” is in the imperative mood—used for commands. The term imperative has the same root as emperor.

The emperor gives you a command and you do it. That was true in the days of the Roman Empire, and it’s equally true at Threads. In this case the emperor is Mr. Z, and he has become a master of the imperative mode. He commands, and we obey.

He always had that Imperial look about him—he even opts for an Emperor hairdo.

I could give so many other examples of disempowerment at Threads, but nothing makes me feel less in control of my experience than my timeline. It’s not really my timeline—it, too, belongs to Emperor Z.

It took Facebook many years to figure out how to limit my control over my information feed. In the early days, I connected with family and friends and got access to everything they shared, starting with the most recent post.

That’s what users want. But over time, Facebook learned that it was more profitable if corporate HQ controlled my timeline, not me. And they found all sorts of ways to do this.

Threads is starting out with the benefit of all that learning. So don’t expect that you will follow somebody on Threads, and get a chronological feed of what they post. Instead you find that:

The Emperor (and his large Imperial Guard) decide how much timeline control is given to algorithms, instead of you. They won’t tell you how they make this decision, but I think it’s safe to say the algorithm has the upper hand.

The Empire also controls what rules are built into the algorithm—and won’t tell you much about those either.

The Empire decides if you see advertisements, and when, and how often.

The Empire decides if you get to see what a friend is posting.

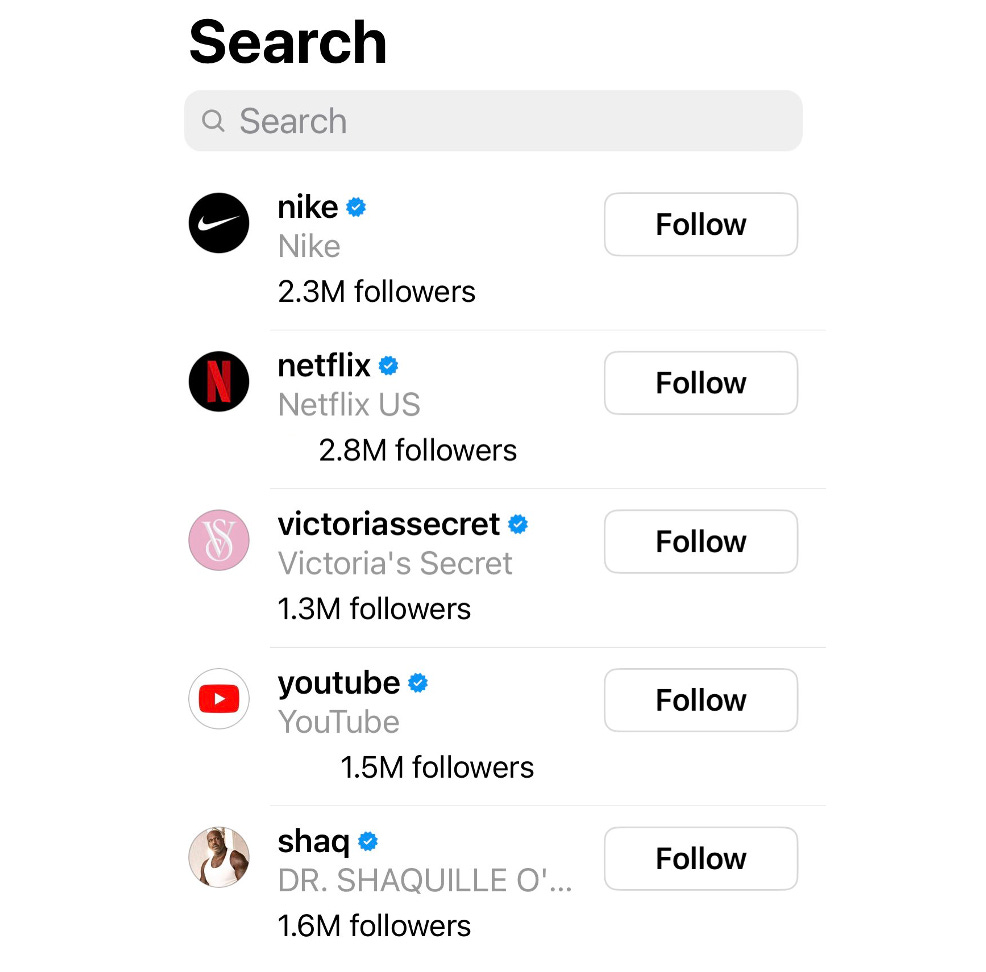

The Empire won’t let you search by topic—you can only do searches on accounts to follow. This is a huge constraint, and makes it virtually impossible to use Threads to follow breaking news stories or subjects of interest.

The Empire won’t let you use hashtags either—probably because users would click on them to bypass the all-powerful algorithm.

And, of course, the Empire decides what is allowed, what is prohibited, what is prioritized, and what is trending.

But that’s only half the story. Because the Empire makes money on both ends. You not only lose control over what you see, but you also lose control over who you reach with your own posts.

If you want to be an influencer—a peculiar but pervasive career goal nowadays—you need to pay for access to your own followers. But even ordinary citizens of the Empire will be constrained in similar ways.

At this point, I need to say something in defense of Mark Zuckerberg and Threads. What he is doing is a travesty of the original vision for social media, but it’s no different than what every other big web platform is doing.

Consider this verdict on LinkedIn, from one of its most successful users:

I grew tired of building my writing brand on platforms where I don’t have any data, or even direct control over what is actually delivered to my followers….

I have a newsletter on LinkedIn with over 300,000 subscribers that I built from scratch. Even though I wrote one of the most heavily subscribed newsletters on the whole platform for many years and published articles responsible for tens of millions of impressions, LinkedIn’s newsletter functionality feels like a black box. The subscriber data is opaque other than basic numbers, the ability to segment the audience is non-existent, and I had no idea how many of my 300,000 subscribers my content was actually reaching each week.

This author has a legitimate gripe. He builds a huge audience for LinkedIn, but with little benefit. That’s the way the new Internet works—and everybody who participates on social media gets a similarly raw deal.

But this author had a solution—he switched his newsletter to Substack. He finally got complete control of his writing, and it was more than just a matter of money. He finally had better metrics, better access to readers, and something resembling a real community.

That’s a useful lesson for all of us. There’s even a way to check out of Hotel California, if you’re determined enough.

Our only way of sending a message is by leaving bogus gated communities, and joining real ones that are open and empowering. It’s worth remembering that our contributions to these platforms provide the entire user experience. Without us, they have nothing.

Even the one choice left to us on Threads—namely, who to follow—feels controlled and claustrophobic.

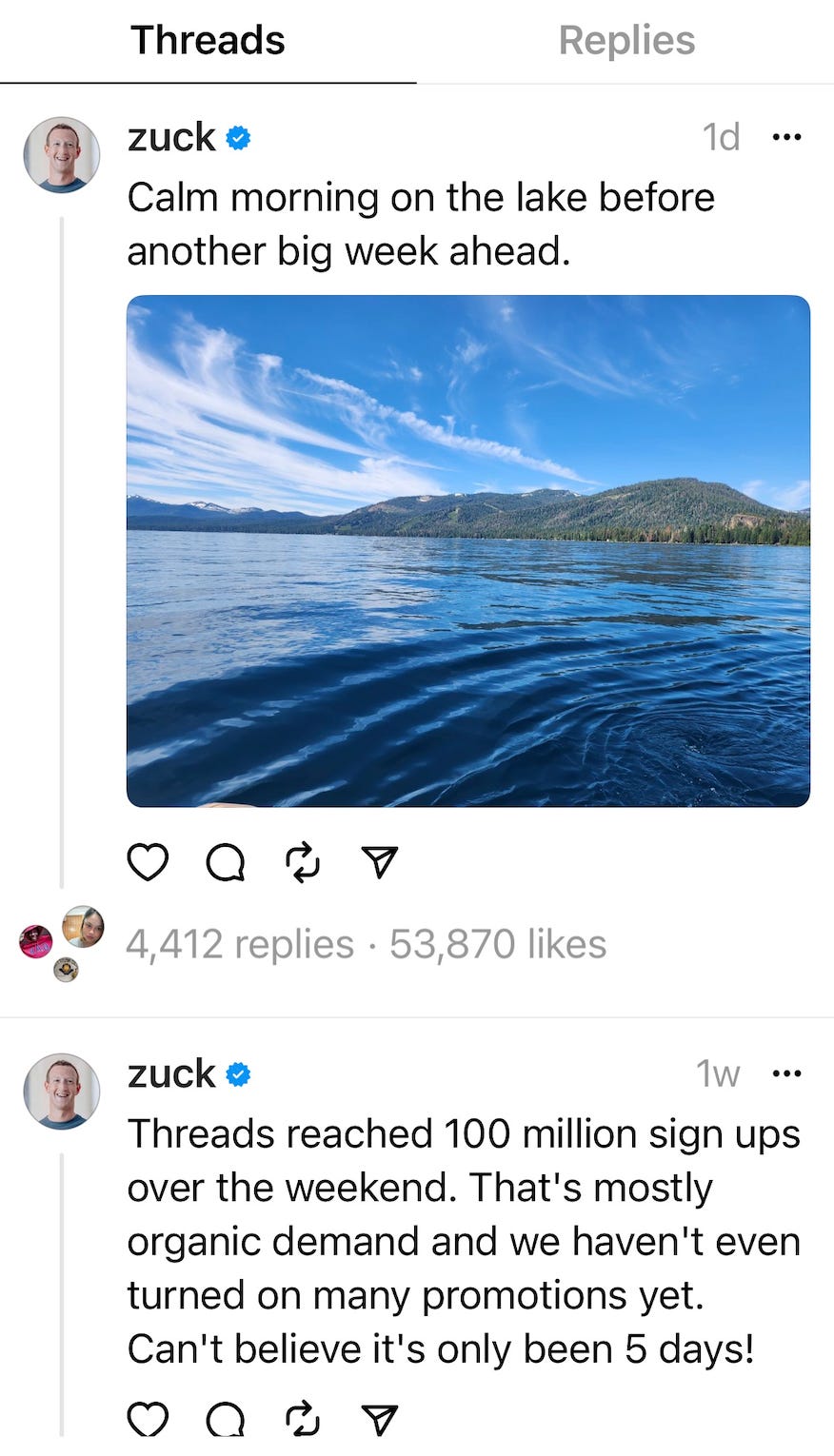

I got a quick lesson on this my first day on Threads. The person I really needed to follow, according to the algorithm, was another billionaire technocrat.

We’ve come a long way from the early days of Facebook—when the promise of social media was putting you in touch with family and friends.

Granny and your old schoolmates don’t matter any more. They don’t have deep pockets, and can’t pay for access. In the new Internet, eveything is pay-to-play.

A couple days later, I revisited the algorithm’s recommendations on who I should follow. This time they delivered these options:

This is downright amusing. These social media sites track everything I do—but still they don’t seem to know that I’ve never bought anything from Nike or Victoria’s Secret. And never will.

I’m not sure how to describe this platform, but it is certainly not a community.

It feels more like a panopticon—that circular prison, where everyone is under surveillance and only sees what they’re supposed to see.

After a few days on Threads, I couldn’t shake off the pervasive sense that this platform is a playground for powerful institutions, consumer brands, and celebrities. It’s not for me.

But it needs me. Or, to put it differently, it needs a lot of people like me. Because Nike wants a captive audience. So somebody needs to play the role of captive.

Maybe some people like getting tied up in ropes and chains—or so I’ve heard. But I’m not one of them.

And I’m not alone—others are already losing interest. The early results show a huge decline in both users and time spent on the platform.

And guess who else is losing interest? The Emperor himself! Mark Zuckerberg has only posted once in the last week—to share one of those celebrity lifestyle photos that are so prominent on the site.

I can’t say I blame him. If I had that swell waterfront view, I wouldn’t waste time doomscrolling through celebrity twaddle and pitches from Nike and Coke.

I will probably do the same thing as Zuck. I’ll check in occasionally on Threads, and maybe put up a few posts. But I’m not pledging loyalty to this club unless I’m given a little more control over my experience.

In the meantime, my main energy will go towards building a real community in places like Substack and private life, where my companions are smart, affable folks, not prison wardens and fellow captives. If we ever hope to create whole cloth out of the tattered and torn threads of the current-day web, it will happen in open and transparent settings like that, not inside an Emperor’s micromanaged playground.

This is the thing that gets me: "This is downright amusing. These social media sites track everything I do—but still they don’t seem to know that I’ve never bought anything from Nike or Victoria’s Secret. And never will."

Years ago someone--and I can't recall who--said something along the lines of, "Facebook has a billion users in it's 'community' and the only thing they can think to do with them is show them ads."

Substack so far seems more in line with the promise of the internet in its early days.

"Or why can’t I access Threads with a desktop or laptop computer browser?"

Because one of the primary functions of Threads is to put a tracking app on a device that you carry with you everywhere so your actual location information can be harvested and sold.