Government funding is set to run out at the end of the day Friday — in less than 48 hours — and lawmakers have yet to strike a deal to avert a government shutdown.

The Republican-led House passed a continuing resolution Tuesday that would extend government funding through September, but Senate Democratic Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said Wednesday that his caucus planned to block the measure. Because of the filibuster rule, the bill needs 60 votes to advance in the Senate, requiring support from at least seven Democrats.

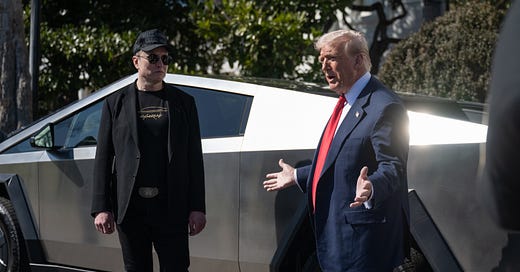

Many Democrats oppose the plan because it lacks any provisions reining in President Trump and Elon Musk from their spree of dismantling government agencies; Schumer’s announcement signals that his party is willing to risk a government shutdown to wage this fight.

But could the chaos of a shutdown actually empower Trump and Musk to reshape the government further?

I’ve put that question to a range of budget experts and shutdown veterans in the past few days, and Democratic lawmakers might want to consider their answers before pulling the trigger. Historically, the executive branch has been able to decide for itself what stays open and what doesn’t during a shutdown; Democrats, I was told, would be left with few options to challenge Trump’s determinations.

The first thing to know about shutdown law is there isn’t very much of it. The main legal provisions here are the Appropriations Clause of the Constitution, which says that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law,” and the Antideficiency Act (ADA) of 1870, which similarly prohibits officials from spending “any sum in excess of appropriations made by Congress.”

But neither of those provisions lay out exactly what should happen when appropriations lapse — which might by why, for most of U.S. history, whenever Congress failed to pass appropriations laws, agencies remained open, continuing to operate despite their lack of funding. It wasn’t until the Carter era that Rep. Gladys Spellman (D-MD) dug up the long-forgotten ADA and began arguing that the law required agencies to shut down during gaps in appropriations.

The idea was so unheard-of that when Spellman made her case to the General Accountability Office (GAO), Congress’ in-house auditor, the agency disagreed with her. But Spellman’s next correspondent, Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti, took her side. It is only because of a subsequent memo Civiletti wrote in April 1980 that government shutdowns came into existence.

“I think the reaction in the office was pretty much, ‘Huh, we never thought about this before,’” Peter Shane, an NYU professor who helped draft the Civiletti memo as a young DOJ employee, told me. But “once we started focusing on it,” Shane added, it seemed to have only “one right answer”: if Congress failed to pass a funding bill, agencies would have to cease their operations.

The Carter White House pushed back against Civiletti’s new interpretation, Shane recounted, leading to a follow-up memo in January 1981, clarifying that government operations involving the “safety of human life or the protection of property” could continue without appropriations.1 That’s still how funding gaps are handled today; those exceptions are what allow people like TSA agents and members of the military — as well as all other employees deemed “essential” — to continue working during shutdowns.

But the exceptions are ambiguous; in shutdowns past, the executive branch has been allowed to fill in the blanks as it sees fit, which would (at least temporarily) give Trump considerable discretion over the size of government.

Each agency sets their own plan for how many people to send home (or “furlough”) during a shutdown; the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), currently led by a group of close Trump allies, oversees the process. “The general principle is, whatever the president and his agents decide is essential…they’re going to go ahead and do it,” said Roy Meyers, a retired political science professor who has written about the history of shutdowns.

John Koskinen, who served as the OMB’s “shutdown czar” during the first extended lapse (under the Clinton administration), told me that the preparations mostly involved discussions within the executive branch, especially at OMB and the Justice Department.

“We were very clear that we did not want people cutting corners,” Koskinen said, but other presidents haven’t been as fastidious. (Koskinen told me that he left a binder of precedents behind to guide future shutdowns, but by the time he returned to government during the Obama era, it was nowhere to be found.)

Shutdowns leave a lot of room for “creative lawyering,” Georgetown Law professor Eloise Pasachoff, an appropriations expert, told me. And if you’re wondering whether Trump might try to push the boundaries, there isn’t any need to speculate: he already did so in his first term, repeatedly.

In Clinton- and Obama-era shutdowns, national parks were closed, sparking public outcry. But during the 35-day shutdown between December 2018 and January 2019 — the longest in U.S. history — the Trump administration kept the parks open, even going so far as to dip into a different pot of money to fund the decision. Similarly, most Internal Revenue Service (IRS) employees were furloughed during previous shutdowns; in the middle of the 2018-19 gap, Trump officials decided to bring back 16,000 IRS workers so tax refunds could continue to be processed.

Overall, the GAO — now charged with tracking ADA violations — accused the Trump administration of breaking the law in at least eight different ways during the shutdown. Trump officials didn’t seem too bothered. Under the ADA, agencies are required to tell Congress when the GAO has accused them of flouting the statute. But OMB General Counsel Mark Paoletta told agencies they didn’t have to do so.

“When an agency of the Legislative Branch interprets a law differently than the Executive Branch, the Executive Branch is not bound by its views,” Paoletta wrote. “ADA reporting requirements should reflect this principle.” Paoletta has now resumed his role in the current Trump administration.

The first Trump team also expanded the definition of “essential” in ways that helped its allies. The mortgage industry successfully lobbied the Trump administration to restart a key program in the middle of the shutdown (“Could you make these guys essential?” one executive asked). Oil and gas drilling permits, which stopped during previous shutdowns, were allowed to continue.

Several presidents have expanded the number of workers deemed essential, but none as aggressively as Trump. “The OMB during the Trump administration allowed agencies to, in effect, ignore the Civiletti memo,” Meyers told me. Then-acting Interior Secretary David Bernhardt has recounted that when he told the president about the national parks decision — which the GAO later deemed illegal — Trump responded: “Look, this shutdown has been going on for quite a while. Why didn’t you do this sooner?”

“If you need to do something that makes sense, you should just do it,” Trump told Bernhardt.

And that was when Trump was surrounded by more guardrails. It is easy to imagine his second administration taking even further steps. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin, for example, announced plans yesterday to begin aggressively rolling back Biden-era regulations, but under the agency’s current protocols, regulatory activities largely stop during a shutdown.

The exact words of the ADA prohibits employees from working without funding “except for emergencies involving the safety of human life or the protection of property.” Under Trump’s energy emergency, could such deregulation be reinterpreted to fit that bill? (Continuation of regulatory activity was one area that the GAO dinged Trump 1 for.)

During the 2018-9 shutdown, immigration court hearings continued for detained immigrants, but not for non-detainees; that policy caused as many as 94,000 hearings to be canceled. Such hearings are a prerequisite for deportations; Trump has declared a border emergency as well, which could be invoked to ensure that his deportation numbers (already falling behind) don’t further lag due to the budget stalemate.

Then, of course, there’s Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), which would unlikely be considered “essential” under current guidelines. But, as with most things in a shutdown, that protocol could easily be changed by executive decree. “Trump could say it’s a national emergency that we shrink the administrative state, and therefore it’s an essential function that DOGE be able to continue to order layoffs and cut off contracts,” Shane said. (“That would be nonsense,” he made clear, while adding “there is no norm-breaking undertaking by this administration that would any longer shock me.”)

“I’m struggling to think of something that Trump has ordered that he would not deem essential in the colloquial sense,” Shane told me. “I mean, if you start from the proposition, ‘Hey, I only order people to do essential things,’ then the scope of what could be described as ‘essential,’ becomes quite expansive.”

In addition to the “emergency” language, the GAO has also acknowledged the executive’s ability during a shutdown to carry out functions relating to the president’s “core constitutional powers” — another ambiguous exception that seems ripe for potential abuse.

If DOGE — and other Trump underlings suddenly deemed “essential” — were at work, but many career government officials are not, it could also potentially make it easier for Musk’s subordinates to access information systems at some agencies. Such access has caused clashes with career staff, but if those officials are on furlough, DOGE might enjoy a freer rein.

Speaking of DOGE, some Democratic lawmakers have raised the opposite concern: whether Trump could furlough more employees than normal during a shutdown, perhaps even viewing it as an opportunity to send them home for good.

Several of the experts I spoke to were dubious that the shutdown would allow Musk to fire any more people than he already is, if only because DOGE is already pushing so many boundaries. “They’re already illegally firing people,” Josh Chavetz, author of “Congress’ Constitution,” a book on the separation of powers, told me. “So I’m not sure that the possibility of a shutdown gives them anything they’re not currently using.”

At least one Trump ally, however, feels otherwise. In a 2023 essay published by the conservative Claremont Institute, a former Trump administration official — only identified pseudonymously, as “Lancelot A. Lamar” — discussed how to “transform shutdowns from the bureaucracy’s shield into the president’s sword.”

Lamar advocated for “America First agency heads,” along with OMB, to control the furlough process “politically,” suspending all programs except for those “the administration wishes to continue.” Lamar also pointed to the Reduction In Force (RIF) process, which the Trump administration has already begun using to lay off employees. Under RIF regulations, agencies are required to part ways with employees if they’ve been furloughed for more than 30 days, which could supercharge the layoff process.

The longtime stance of the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) has been that furloughs during a shutdown don’t count for the purposes of that statute, but Lamar urged the agency to “revisit its current guidance” to end that “extralegal distinction.” This version of the RIF process is faster than the one the Trump team is currently using, but still requires 90 days to implement (a 30-day furlough, plus a 60-day notification period).

For that reason, Lamar urged a future Republican administration to try to continue a shutdown “at least through day 91 when hundreds of thousands of feds would be laid off, reshaping the bureaucracy according to the administration’s views of what is essential.” Employees facing RIF layoffs can still appeal to the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), but the MSPB ceased all operations during the 2018-19 shutdown, which would certainly slow that process.

Contrary to the Trump administration’s public position, according to Wired, Musk has told associates that he wants a government shutdown; the 90-day RIF process was cited in the article.

Trump and Musk have also placed allied figures at all the agencies needed to adjust operations in a shutdown: the acting head of OPM has been helping implement DOGE cuts. Russell Vought, the director of the OMB, has previously advocated for a “radical constitutionalism” in which the president seizes more power over spending. (Vought was also the OMB chief who told agencies to ignore the GAO after being reprimanded during Trump’s last shutdown.) The Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), which plays a key role in offering legal advice during shutdowns, is currently led by Ron DeSantis’ former solicitor general. At the same time, Trump has fired many of the watchdogs who might stand in his way.

Even if the shutdown doesn’t drag on long enough to use the RIF process — though it should be noted that Trump threatened to extend the 2018-19 shutdown for “years” — some lawmakers and experts have speculated that Trump could attempt to simply not ask back non-essential workers who are furloughed.

“You have a Congress which right now is very unwilling to fight by oversight to save programs, even programs that used to be funded and have a base of support,” said Charles Tiefer, a University of Baltimore law professor and former congressional lawyer. “So if there’s a shutdown, and personnel are let go…and then the shutdown ends, but the administration doesn’t restart up an agency, and the congressional committees just look on benignly, then they let the program go.”

Sen. Mark Kelly (D-AZ) recently raised the same concern to reporters: “Who knows what he’s going to want to open back up? That is a huge risk. Maybe they decide that entire government agencies don’t need to exist anymore.”

If Trump does decide to push the boundaries of what a shutdown looks like, it might be difficult to stop him, especially because past shutdowns have been so driven by the White House.

The Republican-led Congress is unlikely to pass any laws hemming him in. Then there’s the GAO, which is empowered to track ADA violations but lacks much enforcement power. “The GAO?” Tiefer laughed, imagining the possibility of the watchdog agency standing in Trump’s way. “Forget it.”

Of course, there’s also the judiciary, but if Trump tries to expand the definition of “essential” — as he did during his first term — in order to keep more federal employees at work in ways that serve his ideological agenda, Democrats might have a tough time using the courts to stop him.

Anyone who brings a lawsuit in the U.S. must show that they have standing, which requires proving that they’ve been injured by the action that they’re challenging. While it’s easy to imagine people who might be injured by too much of the government shutting down, it’s harder to think of who might be hurt by Trump ordering government operations to continue on like normal.

Federal employees, who go unpaid when they work during a shutdown, might be one group. But when some tried to sue after being made to work during the 2018-19 shutdown, none were successful. The cases also took years to litigate, making them an imperfect remedy to begin with: one dispute wasn’t resolved until 2020; another until 2022.

In general, courts are often reticent to intervene in these sorts of disputes: “They’re going to want to stay out of it,” Chafetz told me. Partially for that reason, what exactly counts as “essential” has never been legally tested.

Still, attempting to operate the government beyond the narrow confines of the ADA wouldn’t be without legal risk: under the statute, officials can be fined $5,000 or sent to prison for two years if they work without funding on projects beyond the “safety of human life” or “protection of property” exceptions.

“I don’t know what OMB and/or the Justice Department would actually be willing to approve,” said Zachary Price, a law professor at the University of California San Francisco. “And then beyond that, it’s sort of a question of what agencies and employees do. They have some pretty specific personal risk associated with violating this law. So it people in a really tough position, if the executive branch — the people they’re supposed to count on for sound guidance — is telling them something’s OK when it’s objectively not OK.”

“I think that does sometimes create some constraints within the executive branch,” Price added. “People aren’t willing to spend money unlawfully because they’re personally on the hook under the Antideficiency Act.”

Still, no one has ever been prosecuted under the ADA, and it’s not as though Attorney General Pam Bondi would go through with charging these officials. They could still face liability from a future Democratic administration, Price noted, although he also cautioned that presidents rarely pursue prosecutions (even of the opposite party) that have the effect of limiting executive power. (The pardon power is, of course, also on the table.)

The most dramatic option available to the Trump administration would be for Bondi to rescind the Civiletti memo altogether, returning the government to its pre-1980 interpretation of the ADA: that it does not require shutdowns.

On its face, there’s nothing stopping Bondi from doing so: what’s done by the executive branch can be undone by it as well. “There’s no legal barrier to any attorney general revisiting a prior attorney general’s opinion and revising it in light of what they understand the law to be,” Shane said.

At that point, the only backstop would be the courts — although, again, the question of standing might pose an issue — ruling that the ADA does, in fact, require a shutdown, a question they have never weighed in on. (“Don’t give her any ideas,” Tiefer groaned when I asked about the possibility of Bondi releasing her own memo.)

Moving to end the shutdown unilaterally could serve the political ends of the Trump administration, as well as the president’s self-image as a powerful national savior. “You can imagine him saying, ‘Congress has failed, Congress can’t help you. It’s up to me to save everyone,’” Sen. John Hickenlooper (D-CO) recently told reporters. The Democrats say I’m trying to close the government, but they’re the ones who shut it down, he could say. And I’m the one who reopened it for you.

It’s unlikely, though, keeping the government open would serve Trump’s ideological agenda. (A future Democratic administration might feel differently.) Still, the hypothetical underlines how little case law exists in this area, both because shutdowns have been relatively brief and rare and because Congress and the courts have been content to let the executive branch craft the terms when they emerge. (After all, shutdowns are the executive branch’s creation.)

Instead of repealing Civiletto’s memo entirely, most of the experts I consulted found it more likely that Trump might use the leeway available to him to simultaneously engineer a shutdown more and less aggressive than those in the past, depending on the agency. “I think both of these directions are possible,” Pasachoff told me: Trump moving to more fully shut down agencies he dislikes, while claiming an emergency need to keep open those he does.

The most aggressive (and legally dubious) action Trump could take in this area would be moving to actually access the money sitting in the Treasury during a shutdown: the Justice Department, since Civiletti, has interpreted the ADA to mean the government can make people work during a shutdown, but can’t pay them (or make other expenditures). In a limited way in his first term, Trump experimented with moving money around during a shutdown, in the national parks example.

“I think he views his powers as limitless in a shutdown situation,” Tiefer said. “And so, yes, he would move money around, so that he could increase [immigration] holding facilities. He’s already said that there’s an emergency, so this would just be one more use of the emergency status. And who is there to stop him if he turns to Russell Vought and says, ‘Would you move money from the Department of Education to ICE?’ Vought’s not going to say no. And Pam Bondi is not going to say no.”

“The House GOP’s CR gives Trump & Musk a blank check to steal YOUR taxpayer dollars,” Senate Appropriations Committee vice chair Patty Murray (D-MA) wrote on X recently. “I won’t vote to help two billionaires pick winners & losers.”

But it’s possible that a Trump-led shutdown — following precedents his aides laid carefully during his first term — could be the ultimate “winners and losers” scenario, possibly by manipulating funding or more simply by keeping open certain agencies at the same time as he closes others.

Shutdowns are often treated as a political sideshow, and in many ways, they are. But they also speak poignantly to two highly charged national conversations underway right now.

First, at a time when Washington is hotly debating the size of our bureaucracy, shutdowns offer us an X-ray of which parts of the government we truly cannot do without — or at least which parts the regime at any given time believes so. A shutdown strips the U.S. government down to its parts, forcing officials to start from zero and only add back in what is “essential”: exactly what Musk has advocated on more than one occasion.

Last month’s OPM guidance on the RIF layoffs told agencies to use their shutdown plans as a benchmark, focusing on letting go employees whose operations aren’t considered essential when appropriations lapse. In doing so, the Trump administration explicitly pegged its broader vision to the type of government that emerges in a shutdown, attempting to bring the temporary shutdown definition of “essential” into force more permanently.

Second, shutdowns are nothing if not a high separation-of-powers clash, as Congress invokes its power of the purse to withhold funding from the president. What would it mean to have one now, as the push-and-pull between the legislative and the executive branches — especially in areas of spending — is being tested in ways it rarely has been?

Combining these two dynamics could lead to a combustible, and unpredictable, dispute — but it is one, unlike some other appropriations-focused clashes, in which the executive branch might boast the upper hand. In some ways, a shutdown is a form of Congress standing up to the executive, denying him money. But it can also be seen as lawmakers being forced, by their own gridlock, to temporarily cede pecuniary decisions to the White House, which — because of the post-Civiletti precedents — generally takes the lead in deciding how the government is structured during an appropriations lapse, with little consultation from the other branches.

“There’s a sense in which it sort of throws the ball into the president’s court,” said Chafetz. “A shutdown pumps up the notion that we’re in an emergency and therefore that the president’s executive powers are expanded to deal with the emergency,” Tiefer told me, adding: “He holds a lot of cards” during a shutdown.

All of this is compounded by the fact that there is such a limited legal framework to deal with shutdowns (and almost all of it that does exist was drafted by the executive).

“For what we might call the ‘Civil Rights Constitution,’ there’s a lot of case law,” Tiefer said. “A lot happens in the courts concerning the first ten amendments, the 14th amendment. But the ‘Fiscal Constitution’ goes into parts of Article I and Article II that often there isn’t much case law, there isn’t much litigation. And so some of the fabric that creates stability which you get for those other things, you don’t get for this.”

In other words, if you thought the second Trump administration has been chaotic so far: just wait until it’s put in charge of presiding over a shutdown.

By this point, tragically, Spellman had suffered a heart attack and was in a coma, as she would remain for the next eight years of her life. She is the only House member in history whose seat has been declared vacant by the chamber for medical reasons.

F**k. I really thought that the dems would have leverage by forcing this issue. I really appreciate this post to lay out all the considerations at play here. But it is so discouraging to continue to feel that there will be no way to rein in this administration.

Excellent read

Clarifies the point to Dems it isn't obvious that voting against the CR won't backfire. This administration currently has a lot of levers, obstruction just to be obstructionists may be short-term pleasure for long-term loss (see Grigrich-led shutdown)